Jennifer Roberts (00:00:00):

If a kid graduates from school without knowing that AI exists, they’re not gonna be prepared for what they face out in the world.

Eric Cross (00:00:07):

Welcome to Science Connections. I’m your host, Eric Cross.

Eric Cross (00:00:12):

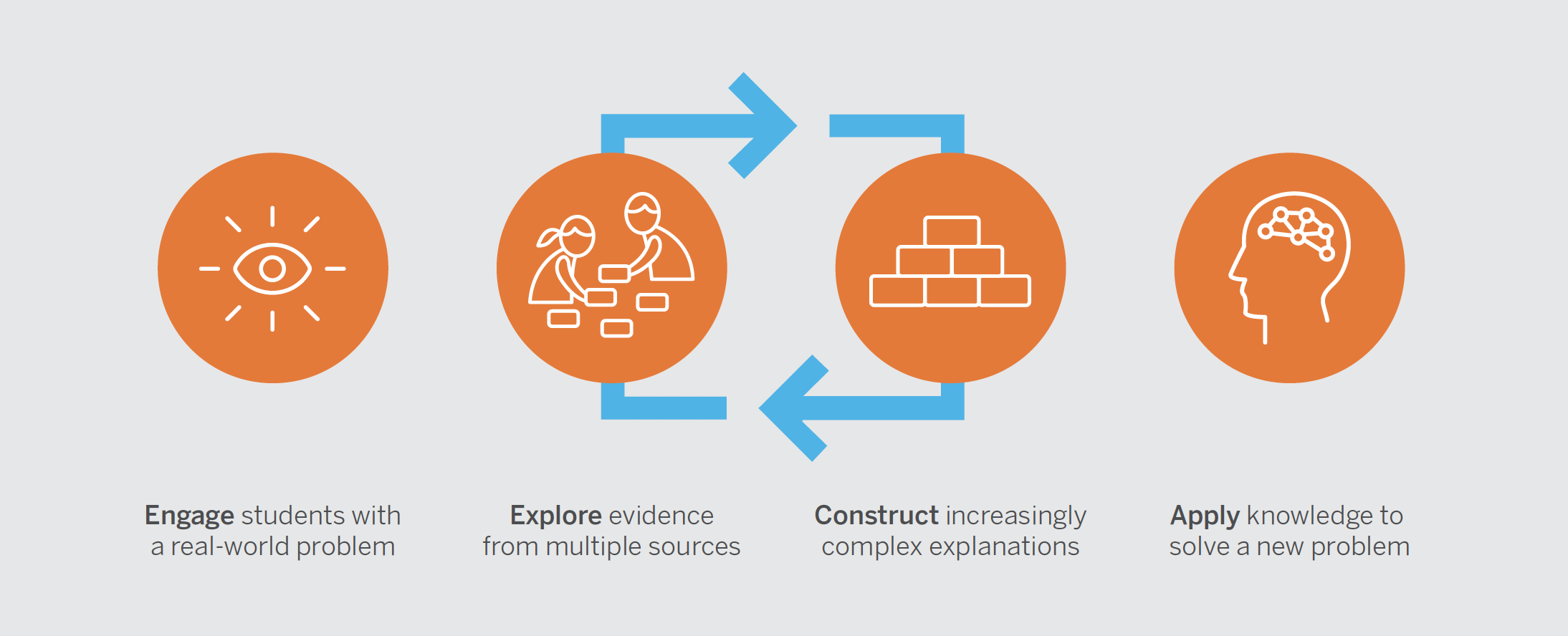

This season of the podcast, we’re making the case for everyone’s favorite underdog, science. Recently we’ve been highlighting the magic that can come from integrating science and literacy. So if you haven’t checked out those recent episodes, definitely go back in your feed after you’re done with this one. This time around, we’re going to deep dive into what artificial intelligence means for literacy instruction, and how science can be a force for good, in responsibly exposing students to AI. To help me out, I’m joined by two extremely accomplished educators. Jen Roberts, a veteran high-school English teacher from San Diego, who among many things runs the website LitAndTech.com. And I’m also joined by fifth-grade teacher Donnie Piercey. In addition to being Kentucky’s 2021 Teacher of the Year, Donnie also has an upcoming book about bringing AI into the classroom. Whether you’ve never heard of ChatGPT or whether you’re already using it every day, I think you’ll find this a valuable discussion about the intersection of science, English, and technology. Here’s Jen and Donnie.

Eric Cross (00:01:17):

So first off, welcome to the show. It’s good to see you all. What I wanna do is kind of start off by introducing both of you. And so we’ll just go K–12. So <laugh>, Donnie.

Jennifer Roberts (00:01:30):

Donnie goes first.

Eric Cross (00:01:31):

Donnie’s gonna go first. Donnie out in Kentucky. Just a little background. What do you teach; how long you’ve been in the classroom; and what are you having fun with right now?

Donnie Piercey (00:01:38):

Yeah, so my name is Donnie Piercey. I’m a fifth-grade teacher from Kentucky. Live and teach right here in Lexington, Kentucky, right in the center of the state. I’m the 2021 Kentucky Teacher of the Year. But I’ve been teaching elementary school for the past … I think this is year 16 or 17. It’s long enough where I’ve lost count, and I can’t even count on fingers anymore. My friends like to joke that I’ve taught long enough where now I can count down. You know, it’s like, “All right, only so many more years left.” But yeah, teach all subjects. Science definitely is one of the subjects that I don’t just try to squeeze into my day, but make sure that … it’s not even a devoted subject, but one that I definitely try to — don’t just have that set time, but also try to do some cross-curricular stuff with it. So definitely the rise of AI in these past few months, which feels like years by this point, has definitely played quite the role, in not just changing the way that I’ve been teaching science, but really all my subjects. So, excited to chat with y’all about it.

Eric Cross (00:02:47):

Nice. I’m excited that you’re here. And Jen?

Jennifer Roberts (00:02:51):

Hi, I’m Jen Roberts. I teach ninth-grade English at Point Loma High School, and that’s where I usually stop when I introduce myself. But for your sake—

Eric Cross (00:03:00):

I will keep introducing you if you stop there. <laugh>

Jennifer Roberts (00:03:04):

I am nationally board-certified in English Language Arts for early adolescence. I am the co-author of a book called Power Up: Making the Shift to 1:1 Teaching and Learning, from Stenhouse, with my fabulous co-author Diana Neebe. Shout out to Diana. I blog at LitAndTech.com about teaching and technology and literacy and the intersection of those things. And I’m looking forward to talking about how AI is showing up in my classroom and the fun things I’m doing with it.

Donnie Piercey (00:03:31):

And one of us is actually secretly a robot, and you have to guess which one.

Jennifer Roberts (00:03:35):

Have to guess which one. Yes. <laugh>

Eric Cross (00:03:37):

That would be super-meta. And you were the CUE — Computer-Using Educator — outstanding teacher or educator? Whatever. Either one. Of the year.

Jennifer Roberts (00:03:45):

I was the CUE ’22 Outstanding Educator. Yes. And I’ve won a few other things as well.

Eric Cross (00:03:53):

The gaming backpack.

Jennifer Roberts (00:03:54):

I’ve won a gaming backpack recently! Yes. I once won an iPad in a Twitter chat.

Eric Cross (00:03:58):

What?

Donnie Piercey (00:03:58):

What’s a gaming backpack? Hold on. We need to talk about that.

Jennifer Roberts (00:04:01):

We will talk about that. <laugh> And then, I was once a finalist for county Teacher of the Year. That’s as close as I got to Donnie. Donnie was the Kentucky Teacher of the Year. He got to go to the White House and stuff. That was exciting.

Donnie Piercey (00:04:13):

<laugh> I mean, to be fair, there’s only three million people in Kentucky, and about what, 50 million people that live in California? <Laugh> So odds are definitely stacked in my favor, I think.

Jennifer Roberts (00:04:23):

So you’re saying we’re even there? Is that, is that what you’re going for?

Donnie Piercey (00:04:25):

Yeah, evens out. Evens out.

Eric Cross (00:04:27):

So I’ve been looking forward to talking to you both for a while now, and talking about artificial intelligence. It’s like the big thing. And both of you, at different ends of the spectrum and in my life, have contributed to this. Donnie, you’ve been sharing so much great information online about how you’re using AI in elementary. Jen, you are the reason I got into education technology years ago, right when I was becoming a teacher. And so being able to talk with you both about it excites me a lot. So first off, for the listeners who may not have any experience with it — and there’s still a lot of people out there who have not been exposed to it, haven’t got their feet wet with it yet — I’m hoping we could start off maybe with an explanation of … we could do AI, ChatGPT, I know that’s the big one. But simply explaining what it is, just for the new person. And whoever wants to start off can tell us about it. Or maybe we’ll start … we’ll, let’s actually, let’s do this: Let’s continue going like K–12? So Donnie, maybe you could … what’s your pitch to the new person of, “Hey, this is what it is”?

Donnie Piercey (00:05:31):

All right. So, AI, artificial intelligence, probably the way that most people are exposed to it, at least since November when it launched, is through ChatGPT. Where if you Google it, you know it’s made by a company called OpenAI. The best way to describe what it is … when you go there for the first time, make an account, it’s free. You have like a little search window, looks like a Google search bar. And instead of searching for information, you can ask it to create stuff for you. So for example, like on Google search, you might type in a question like, “Who was the 19th president of the United States?” Where on ChatGPT, instead of just searching for information, it creates stuff for you. So you could say, you could ask it to, “Hey, write a poem about the 19th president of the United States.” Or, “Write a short little essay comparing, I don’t know, Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King Jr.” And it would do that for you. You know, that’s most people’s first exposure to AI, at least in these past few months. Instead of … you know, it’s artificial intelligence, but it’s not just chatbots. There’s lots of other AI that exist out there.

Jennifer Roberts (00:06:47):

And I think that’s the thing: that people don’t realize how much AI is already in their lives.

Donnie Piercey (00:06:51):

For sure. Yeah.

Jennifer Roberts (00:06:52):

You know, they just haven’t seen … the term that I see being used a lot now is “generative AI.” AI that can produce something. It can produce writing, it can produce art, it can produce a script, it can produce a character. But the AI that has been helping you pick what to watch next on Netflix and the AI that’s helping Google help you get where you wanna go on Google Maps faster, those are forms of artificial intelligence as well.

Donnie Piercey (00:07:21):

Yeah. I mean, even those, when you get that that message in Gmail, and instead of having to type out that response that says, “Yeah, that sounds great,” you can just click the little button that says, “Yeah, that sounds great.” I mean, that’s been in Gmail for years, but that’s artificial intelligence too.

Eric Cross (00:07:39):

Absolutely. So why is it important, do you think, for educators to, to be familiar with it? Like, why are we all so excited about it?

Jennifer Roberts (00:07:47):

So, educators need to know what kids are into, and kids are obviously into ChatGPT. And anyone who’s an educator right now has probably already had something cross their desk — or more likely their computer screen — that was written by AI and passed off as a student’s own work. And that is, of course, the great fear among teachers everywhere, that this is what kids are just gonna do these days and they won’t be able to catch it and children won’t be doing their own work and this and this. But I think the big reason teachers need to know what’s going on is because teachers need to be futurists. Our clientele will live in the future. We teach kids, kids will become adults, adults will live in the world. And so if we’re not thinking about and trying to predict on some level what’s gonna happen 5, 10, 15 years from now … we might be wrong, but what if we’re right?

Jennifer Roberts (00:08:38):

And if we’re not at least trying to think about what is their future world gonna look like, then we’re not serving our students well. I did a whole night talk on that. So I think ChatGPT is part of that. I teach seniors. I had this moment of realization I felt a few months ago. I’m like, “This is gonna be the world they graduate into. They need to know what this is before they leave me.” If I don’t teach them how to use this well, and not the way they’re using it — which is to copy and paste the teacher’s assignment and drop it into ChatGPT and take whatever it spits out and turning that in without even looking at it — if I don’t teach ’em how to use it critically, if I don’t teach them how to write effective prompts, if I don’t teach them how to use the AI as a tool, as a collaborator, then they’re gonna graduate into a world where they lose out to people who do know how to do that. And I think the advantage goes to kids who have access and knowledge of what’s in front of them and what’s available, and can use all of the tools at their disposal. Because when you’re writing in school and you write with a collaborator, that could be considered cheating. But when you do that out in the adult world, that’s considered doing a good job. <Laugh> Being a team player. <Laugh> You know, adults don’t work alone for the most part. And adults are expected to churn out beautiful, perfect content no matter how they got there. So if I’m not teaching my kids how to use this, they’re not being ready. They’re not gonna be ready to be the adults that I want them to be.

Donnie Piercey (00:10:07):

A hundred percent agree. And I also believe … as you know, I teach elementary school. I also don’t think anybody is saying that on the first day of kindergarten, you hand a kid a Chromebook and load up an AI chatbot or ChatGPT and say, Hey, this thing’s gonna do all your work for you for the next 12 years; just coast through life. You don’t have to think creatively. You don’t have to learn how to develop a paragraph or learn how to write a speech or develop an idea. Like, I don’t think anybody’s saying that, because as an elementary school teacher, there’s many days when I’m like, “Y’all, we’re just putting the Chromebooks away today and we’re just gonna go old-school. We’re just gonna maybe just jot down five quick ideas and stand up and present those ideas to the class.”

Donnie Piercey (00:10:54):

Because while AI definitely will, like you were saying, Jen, play a significant role in the lives of our students who are, not just graduating, but the 10- and 11-year-olds in my classroom this year. A significant role in their lives. It’s also really important to recognize that we’re not saying that this means that “Hey, kids don’t have to work anymore.” They still have to put forth that effort. There’s still — one of the ways that you become a good writer is by trial and error. And sometimes that trial and error comes through talking to a teacher or talking like you were saying to a peer or collaborating with a peer and saying to them, “Well, this sentence here, this paragraph here, really doesn’t make sense.” And I do believe one of the ways — especially as AI starts to become more fine-tuned and starts to be embedded more and more in tools like Google Docs and Microsoft Word — is it’s almost going to be a tutor to students.

Donnie Piercey (00:11:56):

Mm-hmm. <affirmative> Where I could very easily see in a few years, or maybe a few months, who knows what Google or any of these other big companies has rolling out, where a student could highlight a paragraph that they wrote simply, and then say, “Hey, proofread this for me,” or “Check for coherence.” Or even just ask a simple question: “Does this paragraph make sense?” Because you can already do that. You can copy a paragraph over into a chatbot and say, “Hey, does this make sense?” You know, “Rate my idea from one to 10,” and it’ll do that for ’em.

Jennifer Roberts (00:12:26):

We did that last week <laugh>.

Donnie Piercey (00:12:28):

Yeah. Right. I mean, that’s the thing. That technology exists now. It’s just not totally embedded yet. But based on what I’ve read and what I’ve seen, that’s gonna happen sooner rather than later. And it’s really, really important that we teach our students that, “No, you’re not just gonna use this, this tool to cheat, but you can use this tool to help you become a more creative student.”

Jennifer Roberts (00:12:50):

This is the use case in my classroom. Can I talk about that? You ready for that?

Eric Cross (00:12:53):

Please.

Jennifer Roberts (00:12:54):

OK.

Eric Cross (00:12:54):

Please.

Jennifer Roberts (00:12:55):

So my ninth graders are writing a comparative analysis essay, where I took them to the student art gallery and I made them pick two pieces of completely unknown student art and take notes on it, so they could go back and write this essay. And as soon as we got back to class, I said, can ChatGPT write this for you? And they all kind of froze ’cause I didn’t tell them what ChatGPT was. And they weren’t sure if they were allowed to know or not. And finally one of them kind of bravely raised his hand and said, “No.” And I said, “Why not?” And he said, “Well, the AI hasn’t seen the art. How can it write an essay about art when the art is completely original that we just went and looked at?” I said, “It’s almost like I planned it that way, isn’t it?” And they laughed nervously. And then I said, “Does that mean it can’t help us with this assignment?” And they said, “Well, no — of course it can’t help us, because it has not seen the art.” And I said, “Well. …” And I open ChatGPT, and I typed in what they were trying to do: “I need to write a comparative analysis essay comparing two pieces of student art on these reasons. And I need to choose which one did it better, basically. Can you help me with an outline?” and ChatGPT produced a lovely outline. And I looked at that with my students and we looked at it together and I said, “This is what it gave us. Would this be helpful to you?” And they’re like, “Yeah, that would be helpful to us.” So we — to be clear here, I was the only one using ChatGPT in the room. They were not actually using it. We were using it together. I copied and pasted the outline that it gave us and put it in their learning management system where they could access it so they could use the outline that the robot provided, and then they could use that to make their own writing better. So then I let them write for a little while, and, after they’d written for a little while, I said, “Does anybody wanna let me share your first paragraph with ChatGPT and see what it thinks of how you’re doing?” And a brave student raised his hand and we took his paragraph and we put it in ChatGPT, and it spit back advice. We said, “This is what I have so far for my first paragraph. Do you have any advice for me?” And we gave it the writing, and the first piece of advice it gave back was very generic, you know, “Add a hook,” you know, like kind of thing. But after that, it started to get more specific about things he was actually doing in his writing. And it started to give him some feedback. And we looked at that together as a class. And I said, “Does any of that feedback help you?” And he said, “Oh yeah, absolutely. I’m gonna go add some revisions to my paragraph.” And other students did too. They looked at the feedback he got and used that to improve their writing. And so everybody went and revised. And I said, “Look, if you take what the robot gives you and you copy and paste it, and you turn it in as your own work, it’s gonna get flagged for plagiarism. And that’s not gonna go well. But if it gives you writing advice the same way I would give you writing advice, and you decide that advice is good, and you take that advice and you incorporate it into your own writing yourself, then the robot’s making you better, but you’re still the one doing your own writing.” And the writing they turned in from that assignment was, was better. It wasn’t written by ChatGPT; it was still about the student art that they found in the gallery. But I showed them a path. Like, it can help you with an outline, it can help you with feedback. Right? These are fair ways to use it that’s gonna make you better. And they really liked that. They really liked — no one had shown them that before. The idea that you don’t just take the teacher’s prompt and give it to it … like, these are new uses to students and worked well.

Eric Cross (00:16:17):

So right now, you both just laid out these ways that you’re using it. And I do this with people that I’m trying to introduce to ChatGPT or AI. ‘Cause I get excited. Anyone could write a 500-word persuasive essay on the use of color in The Great Gatsby or The Outsiders, and they can get something back within seconds. But for a lot of educators, it might feel like the sky is falling.

Donnie Piercey (00:16:43):

Oh, understandably! Understandably. I mean, that totally makes sense.

Eric Cross (00:16:49):

What would you say to them? Donnie, go ahead.

Donnie Piercey (00:16:51):

Yeah. Well, I feel like every teacher kind of goes through the same experience when they see like a generative chatbot. I mean, all these major companies are gonna start incorporating AI, the generative AI piece. And a lot of times, when they see it for the first time, two things. First they’ll say “Oh, but I’ll know that that’s not my students’ writing.” Which, frankly, I think is a good thing, because that tells me that the teachers know their students’ writing. They’ve seen them write in person. They’ve conferenced with them one-on-one. And if a student were to turn something in to me, who I know might be a struggling writer, maybe it’s not their strength, and all of a sudden they’re turning in this10-page dissertation-worthy thesis written at a PhD level, I’m like, “All right, man, you’re nine. Can we talk about where this came from?” <laugh> But I also don’t think that at like the heart, I don’t feel like kids want to cheat. I really don’t. I feel like sometimes like kids are in a situation where they’re like, “OK, I’ve got nothing left. I gotta get this assignment done.” And when those kind of things happen, that’s when we as teachers, we have those one-on-one conversations. Even when I showed my students ChatGPT and even some of the AI image-generating stuff for the first time, and I talked to them about, “What do y’all think about this?” Because, you know, they’re under 13. In my district, ChatGPT is blocked for students. Staff, we have access to it. And that’s just because one, it’s so new, and at the same time, we need to figure out, “What’s the best way they can go about using this tool?” But when we were talking about it as a class, you know, I didn’t want to ignore the elephant in the room. So I asked them, I said, “Hey, do you feel like this is something that you all would use to. …” I mean, I used the word. I said “cheat.” And to be honest, the majority of the students in my class, they were taken aback. They’re like, “What? You think we just would cheat all the time?” Right? <Laugh> And I’m like, “Oh, well good. I’m glad to know that integrity is still alive and well.” But yeah, that’s definitely my thoughts on it, as far as not only the student integrity piece — I think that that’s the big thing that you need to just bring up with your students. Because again, I like to think that I’ve seen my students write enough that if they were going to turn something in that wasn’t their voice, or it didn’t sound like them, like I could have that conversation. And don’t be surprised, too, if in the next … I don’t know, one month to a year, there’s lots of AI detectors that exist. A lot of them are these like third-party things. You can go ahead, but I would not be surprised if in the next year or so, like you start to see those AI detectors be built into Google Docs, into Microsoft Word, into even Canva. And honestly, it’s almost like a fail-safe button for teachers, that we could say “All right, this is telling me that this is 99% probably written by AI.” So you can have that conversation with a student that way.

Jennifer Roberts (00:20:03):

I mean, if you’re worried about it, Formative, right now, will even tell you if something is copy-and-pasted into the boxes that they give you for students to write in. I find that kids who cheat are desperate, you know. Especially at the high school level. They’re panic mode. And, and usually their panic comes from, “I have no idea how to even start this assignment.” And so part of what I wanna use ChatGPT for is to lower that barrier for them. Like, you’ve got an assignment, you don’t know where to start. Tell the robot, tell ChatGPT, about the assignment and ask it for a list of steps. You know, ask it for an outline. Ask it for a time management plan. I see so much tremendous potential for this to help many of my students with IEPs who have executive functioning issues.

Donnie Piercey (00:20:49):

Oh, a hundred percent, right?

Jennifer Roberts (00:20:51):

Yes, a hundred percent. This can be their personal assistant who, you know, instead of me sitting with them one-on-one and saying, you know, “This is the task you need to do, let’s break it down into these six discrete chunks,” the artificial intelligence can do that for them. And it can do that for teachers too. <laugh>

Donnie Piercey (00:21:09):

Jen, I was just thinking about, how long until we see like the phrase artificial intelligence written onto a student’s IEP? I could see that happening very, very soon.

Jennifer Roberts (00:21:20):

Right? They should be able to use that. And then, also, of course, all of its amazing beneficials for teachers. I had to completely rewrite a unit of my curriculum. I knew what I wanted to do. I had some ideas of things I wanted to put in there. And I resorted to, I went to EducationCopilot.com and typed in my stuff that I had: You know, what standards I wanted to cover, what outcomes I was hoping for mm-hmm. <affirmative>. And it generated an eight-week unit for me. And I actually told it then to go back and do it as a 12-week unit so that I’d have more stuff in there to go and cherry-pick to decide what I really wanted to do. But it gave me ideas. It gave me places to start. It saved me an hour of just brainstorming. And I don’t think that was cheating. I still got to go in and decide which ideas were valid. And I still got to … you know, I mean, I’m a teacher. Can I get accused of cheating? I don’t think that’s a thing. It’s—

Eric Cross (00:22:18):

That’s collaborating! It’s collaborating!

Donnie Piercey (00:22:20):

Collaborating! It’s a feature! It’s a feature.

Jennifer Roberts (00:22:22):

It’s Tony Stark talking to Jarvis. You know, they’re figuring it out together.

Donnie Piercey (00:22:26):

Oh, when you use the AI, Jennifer, do you call yours Jarvis? In my class we call him Jeeves. ‘Cause remember Ask Jeeves?

Jennifer Roberts (00:22:33):

I think Eric calls it Jarvis.

Eric Cross (00:22:35):

Yeah. Jarvis is gonna be the AI’s name when, when I can get that fully functioning. There are some things that you had said, I just wanna circle back on. Donnie, Jen — so what I heard was like, best intentions. The part you said about integrity and students wanting to cheat … even the mindset that we go in assuming our students, what they would want to do and assuming best intentions, really kind of frames how you look at this kind of technology. And then Jen, you kind of brought up why students cheat, and realizing that either they don’t feel equipped, or maybe it’s time management, or something else. But most people — and I believe this as an educator — most students want to learn, and they want to be able to perform and achieve. And when they cheat, it’s because they didn’t feel like they could, for whatever reason. Whether it’s it’s outside factors, whether it’s something internal, motivation, whatever it is.

Jennifer Roberts (00:23:24):

Or they were very disconnected and just didn’t care.

Eric Cross (00:23:27):

Sure.

Jennifer Roberts (00:23:27):

This is just busy work the teacher’s giving me, so I’m gonna give it very little of my time and energy. But I think, yeah, it can be that. But if the kid cares about it, if they wanna learn, they wanna learn, you know?

Eric Cross (00:23:40):

Right.

Jennifer Roberts (00:23:40):

This is the day of the internet. Any kid can learn anything they really want to learn. And we see that all the time in our classes. The kid who has zero interest in what I’m teaching in English, but he is an expert coder, and that’s what he wants to spend his time learning. He’s like, “Can I read this C++ book as my independent reading book?” And I’m like, “You know, actually, you can. Go ahead.” <Laugh>

Eric Cross (00:24:01):

Yeah. And for both of you, saying that this makes content more accessible … and I think Donnie, or Jen, you said something about IEPs. I actually put in having it write an IEP to see what would happen. I gave it a prompt for a student’s ability level and I asked it to create a plan. And then I asked it to create a rationale. And it did! And it was good! I went through and vetted it. And right now … you know, a lot of it is funny, ’cause the conversation I’m having with different teachers is kind of like the Wikipedia one. Remember when Wikipedia first got out and everyone was like trying to discourage everybody from using it, because, well, it could be changed by anybody? And now everyone’s like, “Oh, check Wikipedia, and then steal the sources, ’cause they’re already done for you.” Like, the mindset has shifted since then. And I was talking to someone and they said, “Well. …” And I said, “We can use AI, it could be a tutor, these other things. …” And they said, “Yeah, but what happens?” And then insert apocalyptic scenario. Like, what happens if you don’t have access to wifi? And it reminded me of, for some reason, cooking classes. So in the 1700s you probably had to be able to farm to be able to generate your food. Right? Like, you had to get it from somewhere. But if you take a culinary class now, you just go to the grocery store. And someone might say, “Well, but you should know how to farm, ’cause what if there was this worldwide apocalypse and nobody could go to the grocery stores?” <Laugh> And you’re like, “Well, balance of probability though.” You know, it’s like we’ve been really been living in these iterations of life, and I think this next step for some folks … like, we don’t even realize, even like something like bank statements, right? So many folks are paperless. And there’s always a what-if scenario. What if you need it and the internet goes down. But we get so used to to to technology advancing and making our lives different. This kind of seems like that next iteration. And I wanna ask you this question: Are we looking at like the next calculator? The next internet, with this tech? Or do you think it’s too early to say?

Donnie Piercey (00:26:01):

Well, I’ve seen a lot of people compare ChatGPT to a calculator. I’ve seen that pop up on social media. There’s, “Oh well, no, this is like when the calculator was invented. Everyone was up in arms about how ‘that’s not what math students should do.’ Math should be pencil and paper, math should be this.’” However, you can give a kid a calculator and you can give ’em a word problem and they can punch in all the numbers, but they could do the wrong operation or they could put the decimal point in the wrong place, ’cause the student is still the one who’s controlling what’s on the calculator. Where with AI, all you gotta do is just copy it and then paste it into the bot and it’ll spit out whatever the question asked it for. Whether it was, you know, a 500-word rationale or proof for something in geometry, or if it’s analyzing data on a chart, it’ll do all that.

Jennifer Roberts (00:27:00):

Yes. But it’s not that magical. It’s back to what Eric did with the IEP. He put in a prompt and then he knew enough to ask for a rationale and then he knew enough about IEPs to critically read the results he got and make sure they actually worked for what he needed. He had to know all that. He was an expert using it to do an expert thing. My husband’s a computer scientist; he got ChatGPT to help him write an app, and it was a new programming language to him, and he could put in the data and he could ask for things that I would’ve never thought to ask for. But because he knows the language of computer science, he knew what to ask for. And when it gave him results that were bad, he could see that, and he could say, “Yes, but do it again, but without this,” or “make this part more efficient.” He, again, knew what to ask for. So I think the generative AI is, as a partner with humans, a powerful thing. But if the human doesn’t know what they’re doing, yeah. You’re still not gonna get great results.

Donnie Piercey (00:28:03):

<laugh> And I think that’s why I’m coming at this from the elementary school perspective, right? Because in K–5 students are still learning, like, “Hey, where does the decimal point go?” They’re still learning, you know, if you’re dividing by a two-digit number, where does the first digit go, if you go in the old long-division algorithm? And so they’re still acquiring that base-level knowledge that … I don’t know, maybe this is similar to in Jurassic Park when Jeff Goldblum says, “It didn’t take any knowledge to attain,” you know, “they stood on the shoulders of geniuses,” that whole thing. Like they had to acquire the knowledge for themselves, was his whole point. And so that’s why I don’t think it’s exactly the same as the calculator. It is definitely going to change things, in a similar way that the calculator did. But to me it’s just a whole new animal. And I don’t know if it’s going to be like the next internet, Eric — if you’re gonna get little devices that have AI built into it, like a Star Wars kind of thing, like a droid or something that follows you around — all that would be kind of cool, not gonna lie. But whether it’s something that you’ll access through the internet, something that’s built into your TV, that part I don’t know. But I do know that there’s a reason why all of these apps and all these companies are investing so much — not just energy, but time and money into it. Because they’re recognizing. “OK, this really has the potential to change things.” But if used well, and used safely, to change people’s lives for the better.

Eric Cross (00:29:41):

So I definitely hear that you both agree with the statement that if AI ChatGPT was used in the classroom, it could be a force for good. And literacy development. And I wanna shift gears a bit and then come back to the AI. So with that said — and we’re gonna get into some best practices in a minute — in Science Connections right now in this season, we’re making the case for how science can do more in classrooms and in schools. And so I’m I’m curious about what both of you think about the role in science fostering a better future when it comes to AI and education. And this season we’re really talking a lot about literacy. You know, in schools, so often it’s taught in a siloed way. And Donnie, you’re doing multi-subject. Jen, you’re single-subject: English. And we’ve really been trying to make this case for how science can actually support literacy, and these skills that students are trying to develop. So we’re going a little old-school, kind of diving into your content specialty, but maybe even pre-AI, or maybe AI has a component in this. But Don, maybe we’ll start with you. How has science been a way that has been helpful for your own literacy instruction? I know you do a lot of science, because I see your Google Earth stuff and the thing you did with the solar systems back in the day. And I think —.

Donnie Piercey (00:30:54):

Oh my gosh! You remember my <laugh> … wow.

Eric Cross (00:30:58):

That was amazing!

Donnie Piercey (00:31:00):

We haven’t done that since the pandemic. But I had my students go out, and using Google Earth, we built a scale model. Each of the students partnered up and they planned out on Google Earth a scale model of the solar system. They picked an object from around their house and we talked about like, “Don’t pick something bigger than a beach ball, or else, you know, your Neptune’s gonna end up like 10 miles away.” But you know, they just picked like a small ball, like a basketball, soccer ball, something like that. Or football, for international friends. And then we calculated the size of every other planet. And then on Google Earth, using their front lawn as where the sun was, then we went and we calculated where other planets would be, and then we actually drove to those locations and like held up the objects that would represent Neptune, Jupiter, Saturn, and all that. But it was a lot of fun.

Eric Cross (00:31:59):

And is that still accessible? ‘Cause I know you have some websites that you put resources out there.

Donnie Piercey (00:32:03):

Yeah. Yeah, I can … I wanna say on my Resources page — Resources.MrPiercey.com — I’ve got a link on there to a couple of student examples that I can share. And if not, when we get off this call, I’m gonna go on and put them on there <laugh> so people can find it. I’ll even throw on there just the assignment itself. So if you wanted to copy that and do that with your students, you could.

Eric Cross (00:32:27):

Donnie, the reason why I brought that up is because I saw that you had posted that or shared it a long time ago, and I just thought it was the coolest thing that you could totally do with middle-school students or high-school students. Jen, when I became a teacher, you said, “We’re all teachers of literacy.”

Jennifer Roberts (00:32:43):

<laugh> Yeah. I think we forgot to tell them that I was one of your professors.

Eric Cross (00:32:47):

Yes. <Jennifer laughs> One of the people who’ve definitely influenced and shaped my teaching. And that statement has never left my mind: that we’re all teachers of literacy. And I want to ask you, at the high-school level, how can science educators, or how can science — how have you seen it, or how does it, support literacy, when it’s done right?

Jennifer Roberts (00:33:09):

Like I said, I think we’re all teachers of literacy, but I think literacy is bigger than just reading and writing. I don’t think someone is literate if they can’t talk somewhat knowledgeably about what’s happening with climate change. I don’t think someone’s literate if they don’t know what’s going on in the world. And I think so much of what’s going on in the world has to do with science. We’re doing that all the time. If I could teach English just by giving kids articles about science, things to read, that would make my day. Right? We would never read another piece of fiction again. It would all be, you know, what’s happening to the ice sheet in Greenland. My students thrive on reading non-fiction. And then whenever that non-fiction touches on science is even more interesting. And whenever I can get them writing about data, particularly their own data that they collected, I think that’s building those science literacy skills as well. So I think science and English blend together very, very well. I think the literacy aspects of that are fantastic. There are more subject-specific vocabulary words, advanced vocabulary words, in science than any other discipline. And I don’t see why those shouldn’t come up in English as well. You know, my seniors will do a unit at the end of the year on the new space race. Unless I replace it with a unit about generative AI, which I’m seriously considering doing, ’cause I think they really need to learn about bias in AI algorithms and things like that. And I would like to have them read a whole bunch about that stuff. And I wanna give them the open letter that all those CEOs signed that said that AI research should slow down, and make them part of that live conversation about what’s happening in that field. So science comes into that. You know, when we read Into the Wild, we start talking about a whole bunch of scientific concepts. And when it rains in Southern California, we pull up weather maps and look at radar and talk about that and how that works.

Donnie Piercey (00:34:59):

That’s like once every 10 years, Jen? <Laugh>

Jennifer Roberts (00:35:02):

Well, actually, this year it rained a lot. It rained a lot in San Diego. Which is actually very high-interest for them. ‘Cause they wanna know, is it gonna be raining at lunchtime?

Eric Cross (00:35:12):

Jen, you said something … you have your students writing about data?

Jennifer Roberts (00:35:16):

Oh yeah.

Eric Cross (00:35:17):

Can you tell me more about that?

Jennifer Roberts (00:35:19):

So, this is something we’ve done with the ninth grade team for a long time now, is writing about their own data. So it started with a unit about stereotypes and stereotype threat. And they would collect data individually and then they would enter that data into a Google form and then we would give them the spreadsheet of the aggregate data from the whole ninth grade. And then we morphed that unit into one about academic honesty, and they filled out a survey at the beginning of the unit about their feelings about academic honesty and about experiences with academic honesty and cheating and homework and things like that. And then we would do the unit. We’d do all the readings in the unit. And they’d have these “aha” moments about things that were happening at other schools. And then at the end of the unit, we would give them back their own aggregate data and ask them to write about whether or not academic honesty was an issue at our school. And then to support that answer with evidence from their own dataset. So they had that spreadsheet to comb through and figure out, you know, where am I gonna stand on this? We give them the multiple-choice questions we gave them as the graphs, in Google Slides, so that they could write about them and talk about them, too. So yeah, getting kids to write about data. And the the sentence frames we gave them were sentence frames out of, They Say, I Say, from the chapter on writing about science. And <laugh> as they write this stuff, they’re like, “I feel so smart writing this way.” And I’m like, “I know, ’cause you’re writing about big important topics!” Right? And writing about their own data come to think of it is another great way to make an assignment both very personal to them, but also make it ChatGPT-proof, you know, if you’re looking for something that kids can’t just hand to the robot, the robot doesn’t have that data set.

Eric Cross (00:37:08):

Absolutely. And Donnie, at the elementary level, do you, do you make connections between science and literacy? In your class? You talked about with math, definitely with the solar system, but now, I’m curious, what are your newer projects? What have you been working on lately?

Jennifer Roberts (00:37:23):

What’s up now, Donnie?

Eric Cross (00:37:24):

Yeah, what are you doing?

Donnie Piercey (00:37:25):

Oh, man. Well, let me think. I’m just trying to think of some fun projects that we’ve done this year. Science that we can tie in Literacy and also some student creation. Just recently we had a … so I’ve wanted to expose my students to famous scientists that weren’t just white dudes from Europe. So for this year, what I did — and I actually used AI for this — I went into ChatGPT and I asked for 64 famous scientists and it listed them all off. And then I asked it, like, how many of these were white? And I think it said like 61 of them. You know, it had like Neil DeGrasse Tyson, and a couple of other … I didn’t know who they were. So I’m like, “All right, so we need to make this more diverse and make this more equitable.” ‘Cause you know, with the student population in my classroom, try to find equal representation to make sure they can see themselves in some of these scientists. So, eventually got it narrowed down to where I had about 64 scientists. Half are women, half are men from all continents except Antarctica. I assigned these scientists to my students. Some got two; some got three. And their assignment was to go and one, do some individual research on this person, find out what they were famous for, what they were most well-known for, turn it actually into a persuasive piece, where I said, “Hey, you’re gonna have one slide.” And I’ll tell you why I gave him one slide in a minute. On that one slide, you’ve gotta convince the person who sees it that this scientist is the most important scientist since the dawn of creation. I said, “You could use images, text — I don’t care if they were famous for something that you didn’t even understand what it was. It’s a persuasive piece. You’re 10. Go all out. Add gifs, do that whole thing.

Eric Cross (00:39:21):

This is awesome.

Jennifer Roberts (00:39:21):

I wanna do this project.

Donnie Piercey (00:39:23):

And if you picked up on the number 64, and I did this in March, so what we did was throughout the weeks of March Madness of the women’s and men’s NCAA tournament, whenever a game was going on, we had another round of voting. I just paired ’em up. I was gonna like seed them, like 1 to 64 — that’s just way too much work for me <laugh>. So I just kind of did random kind of thing. But all the students had to do — they just saw the slides side-by-side, and the only question they had was, “Based on what you see here, who is the most important scientist? This person or this person?” And it eventually came down to Carl Sagan going up against Marie Curie.

Eric Cross (00:40:04):

OK, that’s a good matchup.

Donnie Piercey (00:40:06):

Yeah, well, the Marie Curie slide, they just liked the radium piece. So they added like some green glowing gifs. And I said, “Guys, it doesn’t always grow glow green.” But whatever. Anyway, eventually Carl Sagan, in case you wanted to know, according to the 10-year-olds in my classroom, is the most important scientist in the history of the world. So I don’t know if I agree with that per se — I think maybe Newton or somebody else might have had something else to say about it — but fun assignment. It was a unique way to expose my students to a bunch of ideas. I remember the student that I assigned Newton, the only thing that that she knew about Isaac Newton was “Didn’t he get hit in the head with an apple?” And I said, “Well, not exactly, I think you might have read or maybe seen too many like old-school cartoons or whatever.” But she ended up doing some research. She’s like, “Oh, I’ve heard of that before! That equal and opposite reaction thing.” Didn’t know what it meant. I had another student that just got really … you know, if you’ve ever been on one of those YouTube kicks where it’s just, you go like nine levels deep onto like, “What does this theorem mean?” Student sits in back of my classroom, I walked by one day and he’s just watching something on like the fifth dimension and what it might be. And I said, “Oh, your scientist got you started on that.” So definitely was a lot of fun. Unique way to combine reading, writing, but also expose my students to some ideas. And we’re definitely gonna do it again. I’ve actually done this assignment before. I picked 64 random elements on the periodic table. But their only slide that they have to make is “What’s your element? What is it used for? And then, why is this the most important element since the dawn of creation?” <Laugh> And, you know, there’s always that student that gets hydrogen. They’re just like “Sweet!” Right? They get excited about that one. <laugh>

Eric Cross (00:41:59):

Explosions.

Donnie Piercey (00:42:00):

Yeah. But then, for that kid who likes a challenge, or that student with the “gifted” label, you give them, like, einsteinium or palladium. Some of the more challenging ones. And they go all out with this. I didn’t use AI for that one, but it was kind of fun, and I figured it’d be neat to share an idea that another teacher could try.

Eric Cross (00:42:20):

Well you probably have at least two teachers right now that are gonna go and try that. And we’re both looking at you. So.

Donnie Piercey (00:42:24):

Go for it.

Eric Cross (00:42:25):

Thanks for that idea. I’m imagining my students coming in with jerseys with “neon.”

Donnie Piercey (00:42:29):

Oh yeah. <laugh>

Eric Cross (00:42:30):

“Neon” on it. Just all ’80s out.

Donnie Piercey (00:42:33):

The game behind it, too, is you tell kids — again, this is just so the 10-year-olds in my class don’t get their feelings hurt — but I say, “Hey, and if your element gets knocked out, you just have to start cheering for whoever beats you in the tournament.” So by the end, you kind of got half the class cheering for one and half the class cheering for whatever.

Jennifer Roberts (00:42:53):

So the only thing I got outta that whole story that I’ve got for you is, as a child I met Carl Sagan. That’s all I got.

Donnie Piercey (00:43:02):

For real?

Jennifer Roberts (00:43:02):

For real.

Donnie Piercey (00:43:03):

So did he talk with that cadence and tone?

Jennifer Roberts (00:43:06):

Yes.

Donnie Piercey (00:43:06):

Like in real life? Wow.

Jennifer Roberts (00:43:07):

Yes. My father was one of the cinematographers on the original Cosmos. And I got to go to the set a few times.

Donnie Piercey (00:43:14):

That’s incredible!

Jennifer Roberts (00:43:15):

I did not appreciate what I was seeing as a child. But as an adult, I’m like, “That was cool. I was there.”

Donnie Piercey (00:43:20):

“You can see my shadow off in the distance.”

Jennifer Roberts (00:43:23):

I mean, maybe that’s part of why I’ve always had an interest in science. I’ve always had fantastic science teachers. Every science teacher I ever had was amazing.

Donnie Piercey (00:43:31):

I credit mine to Mr. Wizard. I don’t know if you ever watched Mr. Wizard and Beakman’s World?

Eric Cross (00:43:35):

I remember Mr. Wizard. Yep. Yep. I definitely remember Mr. Wizard, Beakman’s World, all those. That was on Nickelodeon back in the day. I had to get up early to watch that one. But there’s a YouTube video—

Donnie Piercey (00:43:44):

Six am!

Eric Cross (00:43:44):

<laugh> It was! It was super-early! But there was one, Don, I don’t know if you’ve seen this on YouTube, but it said “Mr. Wizard Is Mean,” and it’s just clips of when he’s—

Donnie Piercey (00:43:56):

Yelling at kids!

Eric Cross (00:43:56):

Chastising. Or being really direct. It’s just one after another.

Donnie Piercey (00:44:02):

He always asked ’em a question and if the kid, you know, didn’t answer it right, he’d be like, “Well, you’re not right, but you’re wrong.” You know, whatever. <Laugh>

Eric Cross (00:44:14):

I have to make sure I’m not subconsciously saying Mr. Wizard quotes when I’m talking in the classroom, when things are happening. But yeah, that video’s hilarious. So I just want to bring us back to AI, and ask this question: Do you think science has a special role to play when it comes to teaching kids about AI responsibly? Does science have a special role in that?

Jennifer Roberts (00:44:36):

I think the responsible piece of AI I wanna teach my students about is the part about the bias in the algorithms and the bias in the training. And I want them to understand how it works, well enough to make informed decisions about how it impacts their lives.

Donnie Piercey (00:44:56):

Hmm.

Jennifer Roberts (00:44:57):

Because I do have concerns about a tool that was trained on the internet. And the answers it gives you is the average of the internet. And do we trust the internet? And the answer from kids is always, “Well sorta, no.” <Laugh> So I want them to understand the social science behind that.

Donnie Piercey (00:45:18):

Yeah. And just along that same point, having the students recognize that just because, you know, you copy-and-paste a question in, the answer it spits out might not always be correct. So, teaching them that just like you would with a source that you find about a topic that you’re researching, you’ve gotta fact-check.

Jennifer Roberts (00:45:44):

It’s just like being a good scientist. A good scientist wouldn’t always accept a single result or the first result. You know, you would look at multiple angles. You would try things different ways. Last week I took the article my seniors were reading about victim compensation after 9-11, and in front of them, I gave ChatGPT, I said, “Are you familiar with this article by Amanda Ripley? And ChatGPT came back and said, “Oh yes, this was written in the Atlantic in 2020 and it’s about these things, blah, blah blah.” And my students looked at that and went, “That’s not the article we read.” And I said, “I know. It got it wrong. That’s amazing!” Yeah. And I was so happy that it got it wrong! ‘Cause I wanted them to see that happen.

Donnie Piercey (00:46:21):

And I guess one of the big science questions there, or one of the big science components there, is that idea of inquiry. Right? It’s almost like you have to teach students how to ask those deep questions about what AI spits out.

Eric Cross (00:46:35):

All of those tips are great. And it leads me to this last question I want to ask. New teachers that are out there — it actually doesn’t even matter; new teachers, experienced teachers, all of us are kind of new at different levels of this race. We’re all kind of starting it together. I mean, it hit mainstream. We’re all getting exposed to it. You all really dive into it. When tech comes out, I know you two really like, “OK, how can we use this to transform education and do awesome things for kids?”

Donnie Piercey (00:47:04):

Usually, when new tech comes out, “How can this make my life easier?” is usually the question. Yeah.

Jennifer Roberts (00:47:09):

“How can I save myself time with this?” Yes.

Donnie Piercey (00:47:11):

“How can this result in me watching more TV and you know, less grading,” sometimes.

Eric Cross (00:47:16):

And I start there like you, but then I end up more time that I fill with another project. And I need to learn how to stop doing that. I’m like, “Oh! I got more free time! … to go take on this other task.”

Jennifer Roberts (00:47:28):

Oh, all of my tech adoption is driven by “how can I work less?”

Eric Cross (00:47:32):

So you’re you’re talking to a new teacher, teacher’s getting exposed to this, they’re starting the school year or they’re just getting their feet wet with it. What advice would you give them about AI, incorporated into content or even just best practices? Where you’re at right now in your own journey, and someone’s asking you about it —what would you share with ’em? And Jen, I want to start with you.

Jennifer Roberts (00:47:53):

So, the first thing I did is I was in the middle of grading, you know, 62 essays from my seniors about Into the Wild, when ChatGPT became a thing last November. And I wanted to see what would happen. So the first thing I did was take the prompt that I had given my students and gave it to ChatGPT, ’cause I had just graded a whole bunch of those essays and my brain was very attuned to what my rubric was doing and what I was expecting as the outcome. So I could take what ChatGPT gave me as that quote unquote “essay” and evaluate it critically. And I was ready to do that. So my first advice is take something you’re already asking students to do and ask ChatGPT to do the same thing. So that as you look at the student results, you can compare that to what ChatGPTgives you. If what you’re finding is that ChatGPT can generate something that would earn a decent grade from you, you might need to change that assignment. And it doesn’t need to be a big change, but it might need a tweak or something, so that it, it does rely on the student voice, the students to do something more personal. I’m finding very helpful in my classroom is having my kids do projects where they are recording themselves on — I like Flip. So they’re writing a scene together and they’re having to record the scene together. And I’m emphasizing more of the speaking roles than the writing roles necessarily. So yes, first, take something you’re already doing, paste in to ChatGPT, see what the results are, see how that fits with what your students are doing, and then do that for every assignment you give and just sort of see what comes out of that, and see which assignments are failing and which assignments are working. ‘Cause that’s gonna give you a sense, when you do see one of those results from your students, you’ll be able to recognize it. But it’ll also help you tweak your assignments and decide, “How can I make this a little more original or a little bit more authentic for my students?” And if the robot, if the AI, can’t generate a response, what could the AI do that would be helpful to your students? Would be my next question. So can you use the AI to help them generate an outline? Can you use the AI to help them generate a list of steps to help them get started? And when you’re comfortable enough doing that by yourself, then don’t be afraid to open it in front of your class. If it’s not blocked at your school site, which I hope it’s not. Because I think the advantage goes to kids who have access to this in the long run, or at least see what it is and know what it is. Right? Because if a kid graduates from school without knowing that AI exists, they’re not gonna be prepared for what they face out in the world. So give them a chance to see you using it. Model effectively using it. I have a blog post about that. I just wrote it. LitAndTech.com. You can check that out. “Introducing 9th graders to ChatGPT.” How it went, right? There’s a chart there you can have. It’s my very first draft of this, but it seems to be very popular. So, you know, show students how it can be used as their mentor. If I can’t come read your paragraph because I have 36 kids in my classroom and I cannot stop and read everybody’s first paragraph, can you, if you want to, give your first paragraph to ChatGPT and ask for advice? And will that advice be helpful to you? So showing students how it can be used responsibly is, I think, something every teacher should be doing right now. And don’t hold back just because you’re afraid you’re gonna be teaching them what this is. They know what this is. Right?

Donnie Piercey (00:51:13):

They know what it is.

Jennifer Roberts (00:51:13):

Especially if you teach high school. They know what it is. I’ve had parents thank me for showing them how to use it responsibly. You know, this can actually be a really useful tool, but if you’re trying to make it do your work for you, it will probably fail you. If you’re trying to use it to help you do your work, it will probably be helpful. Sort of the way I’m breaking it down for them at this point. You want the great metaphor? The great metaphor is if you build a robot and send it to the top of a mountain, did you climb that mountain? No. If you build a robot and ask it to help you get to the top of the mountain, and you and the robot go together, did you climb that mountain? Yes.

Eric Cross (00:51:53):

I like that. I’m thinking through this. I’m processing that now.

Donnie Piercey (00:51:57):

Me too.

Eric Cross (00:51:59):

Yeah. I just imagine a robot holding my hand climbing Mount Everest and I’m like, “Yeah, I did it.”

Donnie Piercey (00:52:04):

If I got a robot though, like I would have to dress it like Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator 2. Like I would just have to.

Eric Cross (00:52:10):

Of course.

Donnie Piercey (00:52:10):

Of course.

Eric Cross (00:52:13):

Donnie, same question. Advice. Teachers getting immersed into it. Tips. What would you say?

Donnie Piercey (00:52:20):

So, I would definitely agree with everything that Jen said. Just, if anything else, to familiarize yourself with it. Almost like pretend like it’s a student in your classroom and it’s answering questions, just so that way you can see what it can do. And you’re kind of training yourself, like, “Oh, well, if I ever need examples, exemplars.” If you’re in a writing piece and you don’t wanna sit there and write out four different types of student responses — you know, advanced writer, beginning writer, whatever — great way to to do that is you just—

Jennifer Roberts (00:52:48):

Oh yeah. We did that.

Donnie Piercey (00:52:48):

—copy the prompt in and give a beautifully written piece that a fifth grader would be impressed with. Boom. It’ll do it for you. In my classroom, the way that I approach it is I kinda look at AI as almost like this butler that I don’t have to pay. That if I need it to do something for me, it’s just bookmarked. I can click it. And I mean, sometimes I just talk to it like it’s a person. And it’s almost like, in the chat window, I’m just rambling at it, what I’m trying to do. And it’s almost like I’m talking to a coworker, and I’m trying to hedge out some ideas for a lesson. Simple example: For a science lesson, if you’re trying to come up with … let’s say you’re a fifth-grade — or, sorry, I teach fifth grade. Say you’re a seventh-grade science teacher. And you’re trying to teach the students in your class about Newton’s third law of motion. You know, every action [has an ] equal and opposite reaction. Look around your room. See what you have. Maybe look around and you’re like, “All right, I got a whiteboard, microscope, I’ve got magnets, a cylinder. …” And you just copy all this stuff into ChatGPT. Say, like, “Hey, I have all of these items. Cotton balls, peanut butter, whatever.” And say, “I’m trying to teach students Newton’s third law of motion. Give me some ideas of some ways I could teach it using some of these materials.” And it’ll do it! It’ll give you like five to 10 ideas!

Jennifer Roberts (00:54:15):

And then tell it what your students are into. Like, my students are really into basketball. Can you work that into this lesson?

Donnie Piercey (00:54:21):

Yeah! They’re into the Avengers! Hey, find some way to tie Spider-Man into this. You know, that was a pun that didn’t go so well. But, you know <laugh> figure out some way that you could incorporate this and it’ll do it. And Eric, like you said, it won’t be perfect. Right? But if anything else, if you’re a starting teacher and you’re trying to brainstorm ideas — try it.

Eric Cross (00:54:44):

And Donnie, as you were saying that, I was thinking — first, I imagined Spider-Man shooting cotton balls with peanut butter all over them — and then my mind went to having students have these items, like you were saying. And then they create labs, working alongside AI. To do inquiry. To create a lab about something, and then going and performing and collecting data. OK, that’s — now I wanna go do that tomorrow!

Donnie Piercey (00:55:10):

Listen, it is so easy to do. If you have an extra computer in your classroom. … We were talking about Jarvis and Iron Man and Tony Stark earlier. Make a new chat in ChatGPT. Tell it, “I want you to pretend that you are Tony Stark. Only answer questions as if you are Tony Stark.” Or “Pretend you’re Jarvis.” Whatever. “Stay in character the whole time. I’m going to have sixth grade students come up to you and ask you questions about science or forces of nature, and only answer questions like you’re Iron Man.” And guess what? You keep that station in your classroom. Students are working on a project — you know, in elementary school, a lot of times we’ll have that, “ask three before me” — you’re supposed to ask three friends before you go and bug the teacher. Well, maybe one of those “three before me” can be that little computer station, where they go up and ask Tony Stark a question, and then it answers them as Jarvis or Iron Man. I mean, we’re really just scratching the surface with all this AI stuff. And as more and more companies and more and more creatives are gonna start to realize everything that it can do, we’re gonna start to see it more and more. And hopefully we as teachers can really figure out how to use this tool to, of course, help students, but also help them be creative and explore and learn on their own.

Eric Cross (00:56:35):

That’s amazing. And just both of you are just dropping gems right now. And I wanna wrap up by saying — and I’ve said this before on earlier podcasts I’ve done — but at this phase in my life, the people that I’m the biggest fans of are teachers. And it’s true. I don’t mean that in a cliche way. When I watch celebrities and things like that, when I watch professional sports, that doesn’t fill me the way it used to when I was a kid. At this point, as a professional, I get inspired by other educators who are just doing awesome things. And when I think about educators who are doing that, you two are on that list of people that make me better. And when I get better, I can do better things for my kids. And so, one, I want to thank you for staying in the classroom and continue to support students. They’re so lucky to have you both. The second thing I wanted to say is, Jen, I wanna start with you. Where can people — and I know we said at the beginning — but where can people find the stuff that you put out? You got blogs, your social, your book.

Jennifer Roberts (00:57:28):

I got lots of social. Twitter, I’m JenRoberts1 on Twitter. And then my blog is LitAndTech.com. And then I’m on lots of the new social too, the Mastodons, the Spoutables, the Posts — those kinds of things — as just Jen Roberts, because I got in early and I got my real name without a 1. And there was some other one I’m on recently that I’ve forgotten about. But there’s lots of ’em. They’re fun. And I’m Jen Roberts. You can find me there.

Donnie Piercey (00:57:56):

And I’m SergeantPepperD on AOL, if anyone’s interested.

Eric Cross (00:58:00):

If you wanna hit Donnie up on AIM. <Laugh>

Donnie Piercey (00:58:03):

SergeantPepperD.

Jennifer Roberts (00:58:04):

You know, speaking of rock stars and people who do amazing things, I did write a blog post about using ChatGPT in the classroom, but I hear Donnie wrote a whole book.

Eric Cross (00:58:13):

Oh yeah. So, Donnie! Donnie, that’s a great segue. Thanks Jen. Donnie, how do people find out more? And can you tell us about this book you wrote, that’s coming out in the summer?

Donnie Piercey (00:58:22):

Yeah, so the book I wrote is called 50 Strategies for Integrating AI Into the Classroom. It’s published by Teacher Created Materials. They reached out to me. They had seen some of the stuff that I was doing, not just with ChatGPT, but also some image-generating AI stuff. You know, I got featured on Good Morning America, which was kind of cool. And they saw that and they said, ‘Hey, that looks really neat.” Reached out to me and asked me to write a book. And the idea behind the book, that launches this summer, it’s just 50 ideas, 50 prompts, different things that, as a classroom teacher, that you can do. So, you know, I think there’s so many AI books that are out there now. A lot of them are big ideas, which I think are important. Definitely important discussions that need to be, have around, the ethics of AI. What’s the role that AI should play in the classroom. But I just wanted to write a book, kind of like the discussion that, that Jen and I were just having, which is like, “Can we just share a whole bunch of ideas, different things that we could try with our students?” So definitely check it out. And I appreciate you giving me a shout-out too. That was cool, Eric. Thank you.

Eric Cross (00:59:35):

Of course. Definitely. And Donnie, your Twitter is again. …

Donnie Piercey (00:59:39):

Oh, @MrPiercey, M R P I E R C E Y.

Eric Cross (00:59:44):

Follow Donnie. Follow Jen. Tons of stuff on there. Both of you, thank you so much. For your time, for talking about students and how we can take care of them, science, literacy, AI. I hope we can talk about this again. I feel like even if in just six months, we might be saying different things. In a year, the landscape might completely change. And that makes it really fun. But thank you both for being on the show.

Jennifer Roberts (01:00:04):

Thank you for having us, Eric.

Donnie Piercey (01:00:05):

Thank you so much, Eric. We appreciate it, bud.

Eric Cross (01:00:10):

Thanks so much for listening to my conversation with Jen Roberts and Donnie Piercey. Jen Roberts is a veteran English teacher at San Diego’s Point Loma High School and author of the book Power Up: Making the Shift to 1:1 Teaching and Learning. You can keep up with her at LitAndTech.com. And Donnie Piercey is a fifth-grade teacher from Lexington, Kentucky. He hosts the podcast Teachers Passing Notes. Stay up-to-date with him at Resources.MrPiercey.com. And let us know what you think of this episode in our Facebook discussion group, Science Connections: The Community. Make sure you don’t miss any new episodes of Science Connections by subscribing to the show, wherever you get podcasts. And as always, we’d really appreciate it if you can leave us a review. It’ll help more people and AI robots find the show. You can find more information on all of Amplify’s shows on our podcast hub, Amplify.com/hub. Thanks again for listening.