The power of productive struggle in K–5 math

Why fluency matters in K–5 math education

Lesson creation: The playful side you never knew existed

This is one of the best things I have ever worked on.

Every discussion teaches kids about math—and about themselves.

Among many other reasons, discussions are important because they’re moments when the teacher assigns value to students. In a discussion, the teacher says, “Hey—I have precious little time to teach what I know. Still, I’m going to dedicate some of that time for you to share and talk about what you know.” That’s a moment when students learn about math, but also that their own ideas have value.

Discussions are difficult, and “more wait time” is rarely the reason.

There are a few reasons why discussions frequently fail, and it’s rarely because the teacher didn’t give students enough “wait time” to respond, as is commonly believed.

1. The question was hard to understand or find your way into. For a long time, I’d ask my kids at dinner, “How was your day? What happened?” And my kids wouldn’t have much to say. Lately, I ask them to tell me two things about their day that happened and one thing that didn’t, and we all guess which was which. It’s an easier prompt, one that kids can find their way into with ease and then use as a launching pad into a larger conversation.

2. There isn’t enough to talk about. If your math class consists of a lot of binary, right/wrong questions, what is there for anyone to talk about? “A lot of us got this one wrong. Here’s a pie chart that shows how wrong we were. How about I show you how to do it?” That’s fine, but it isn’t a discussion, and it’s quite often a very dreary classroom environment for children.

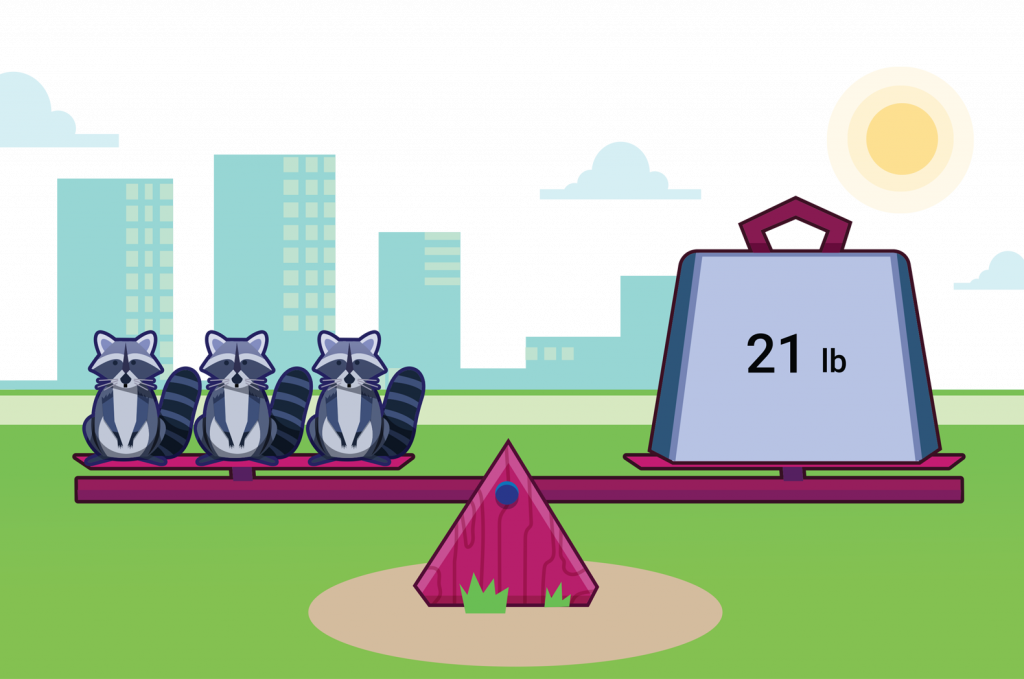

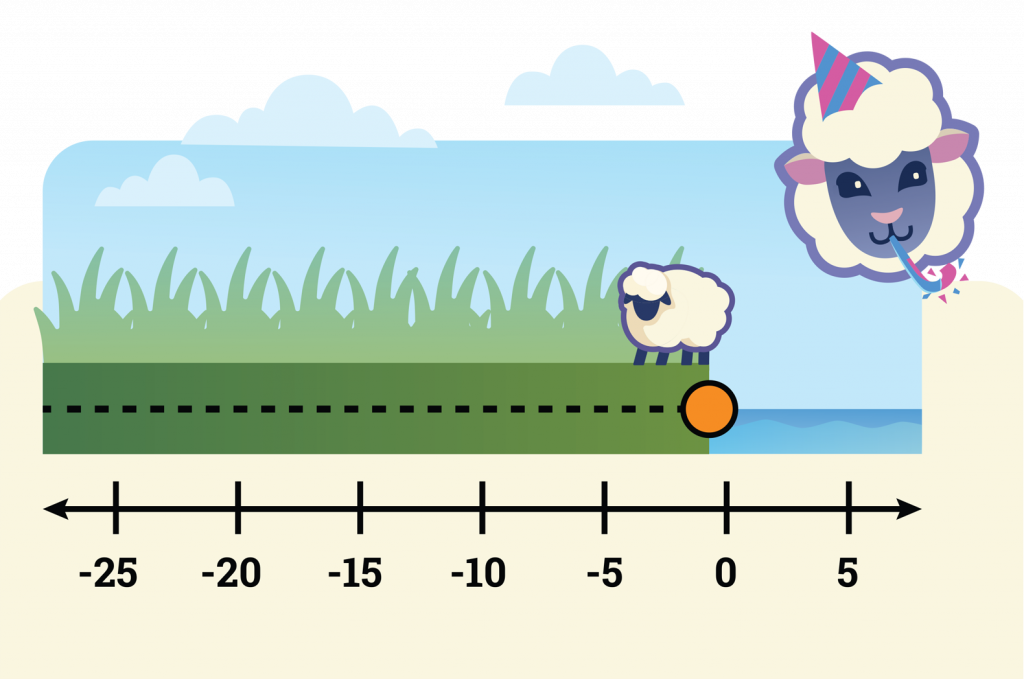

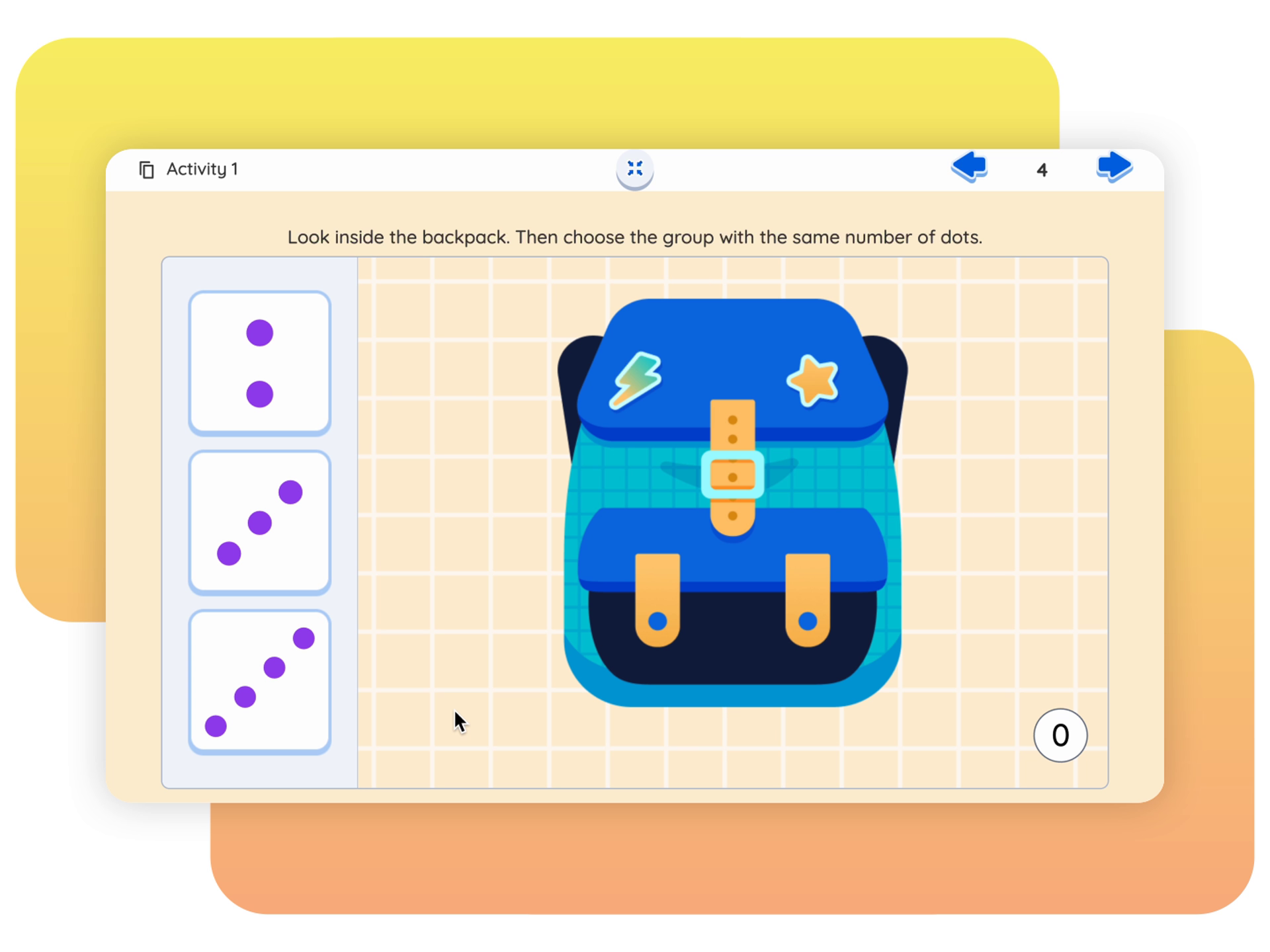

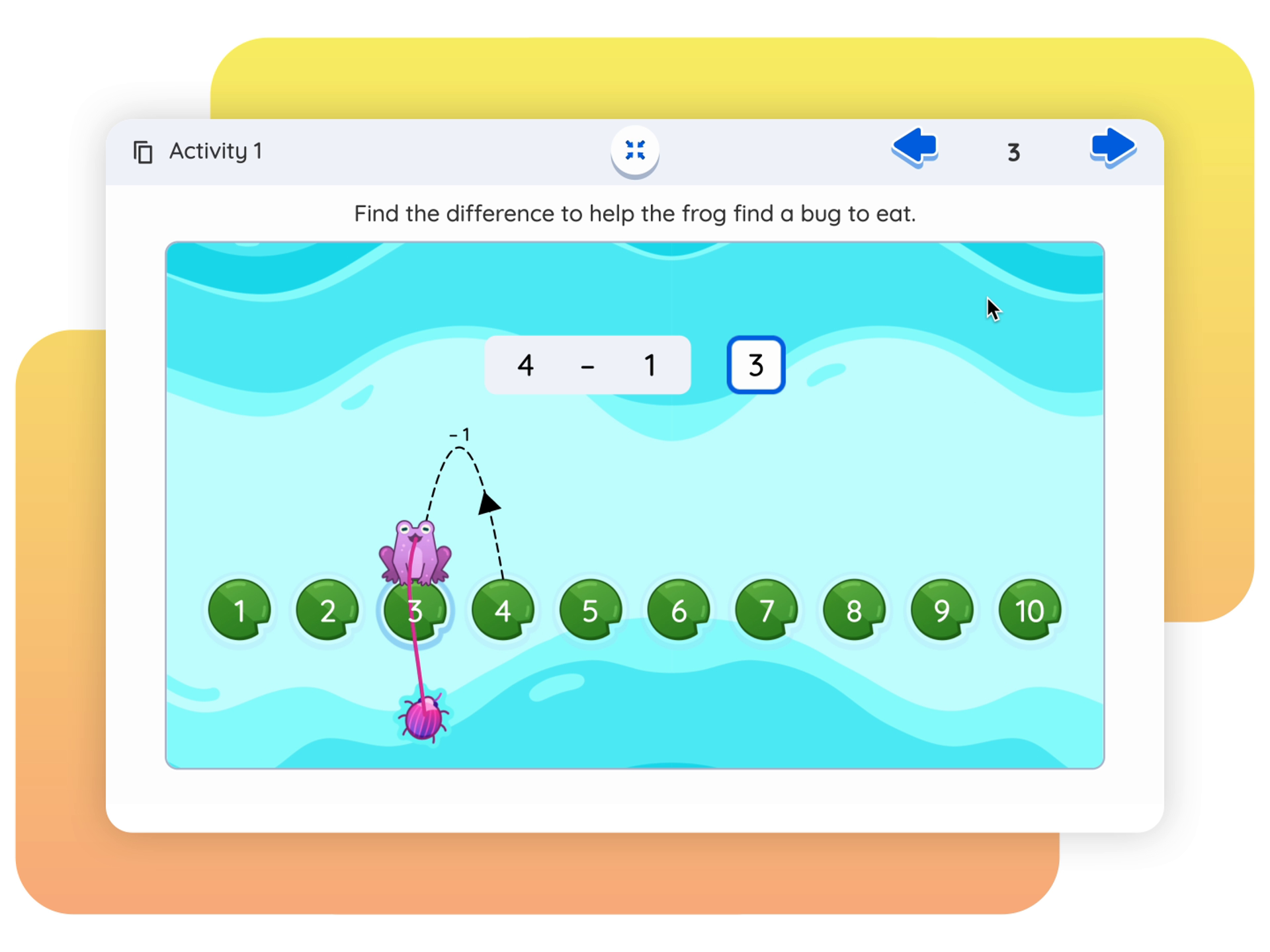

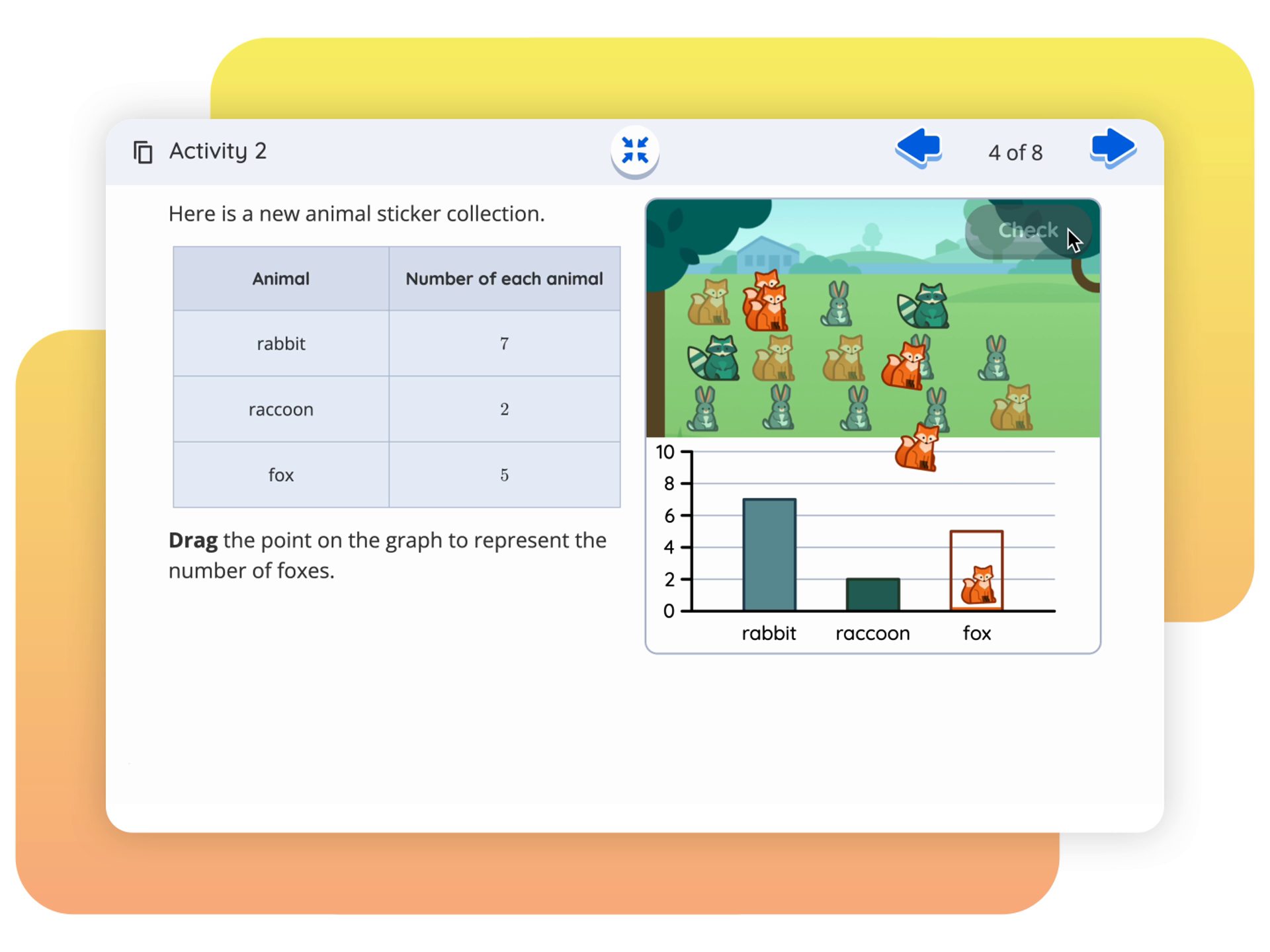

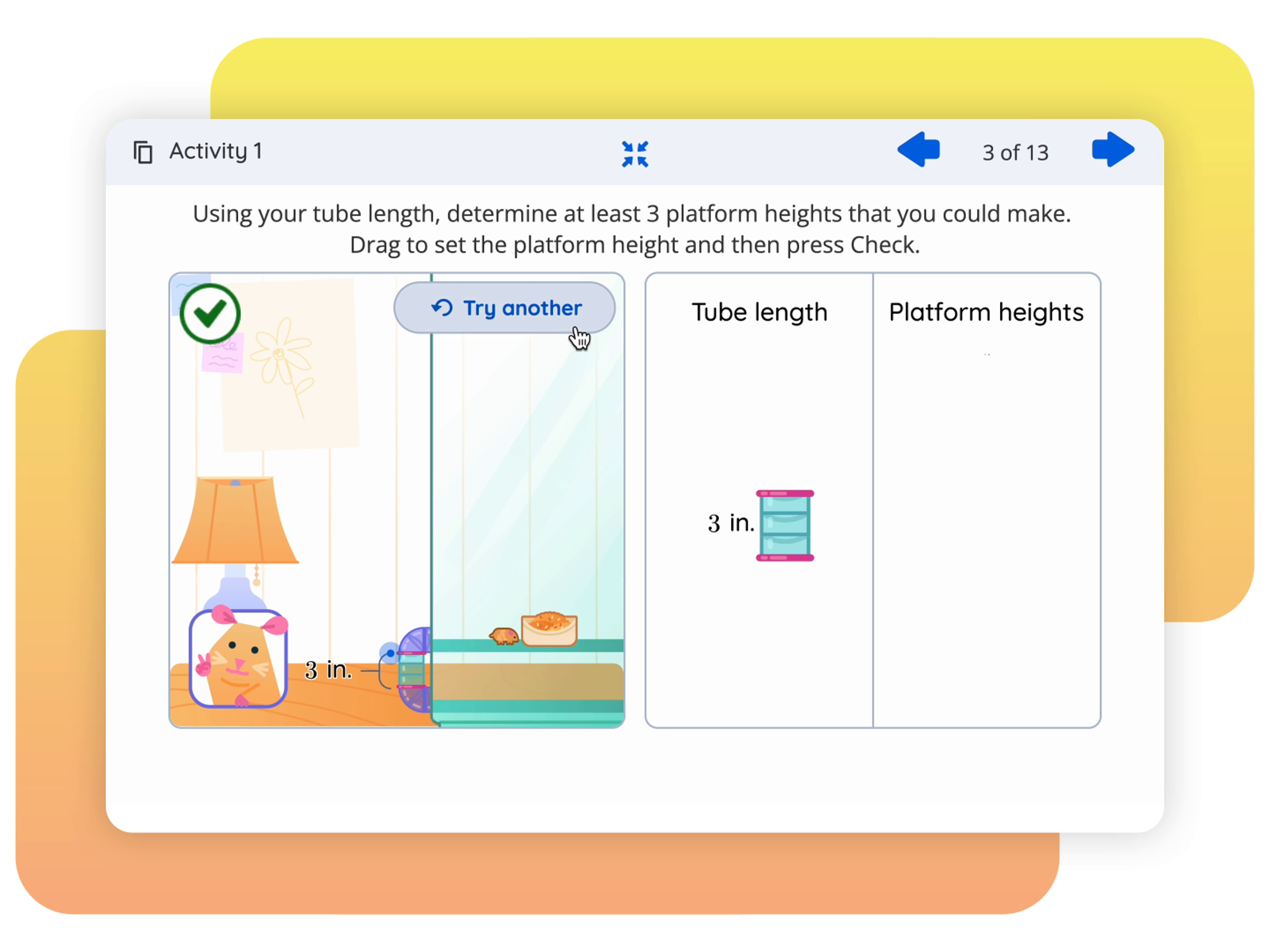

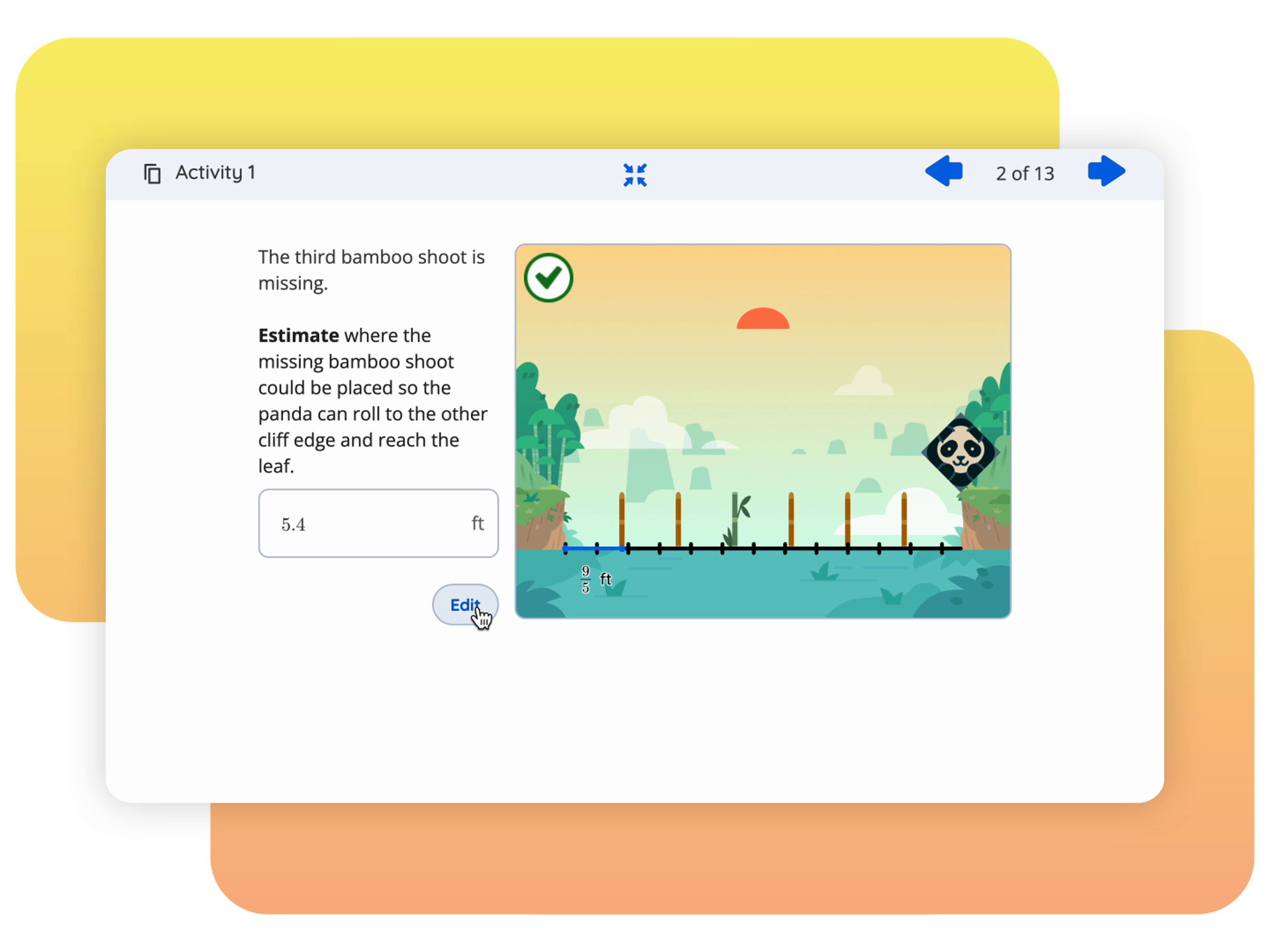

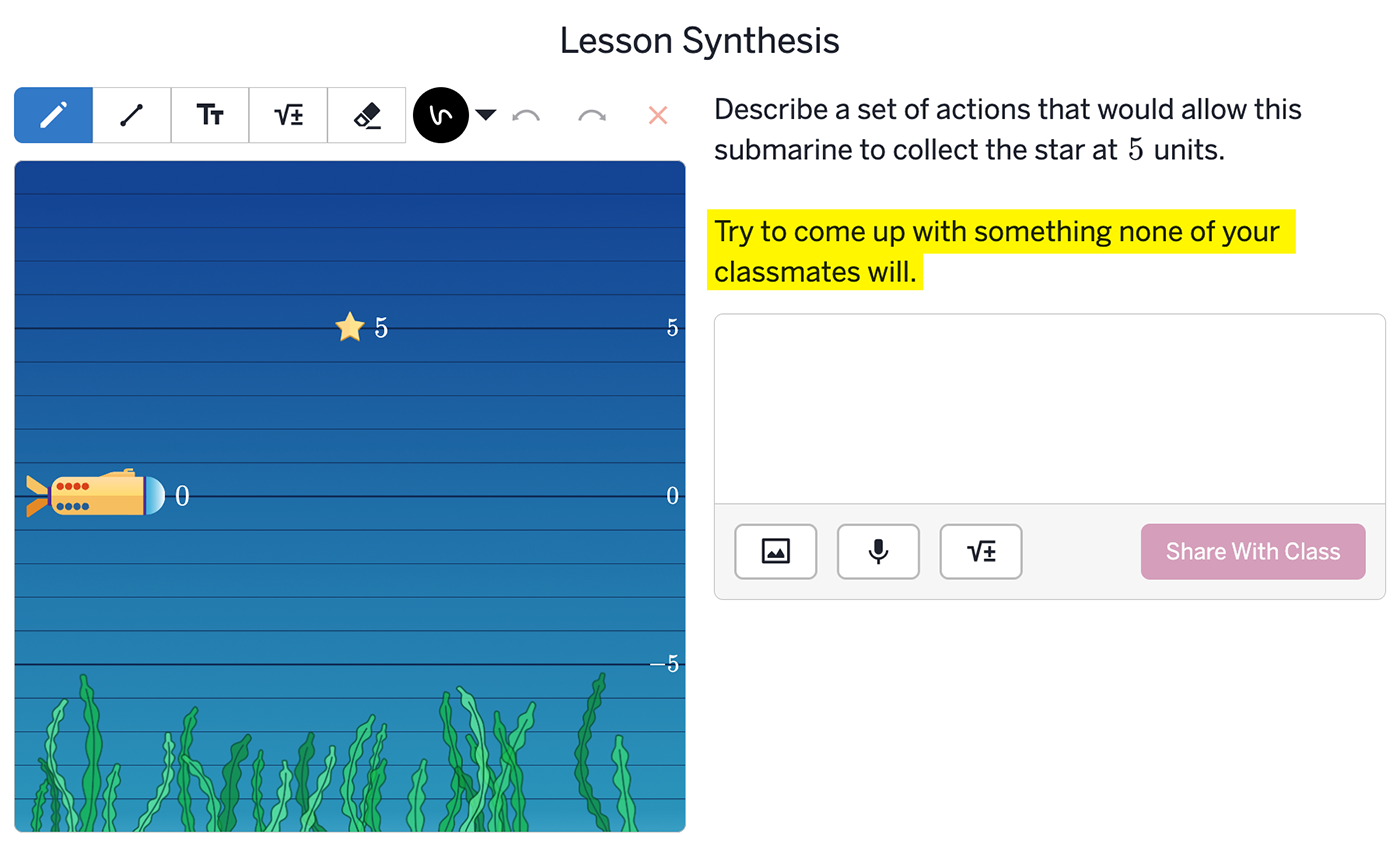

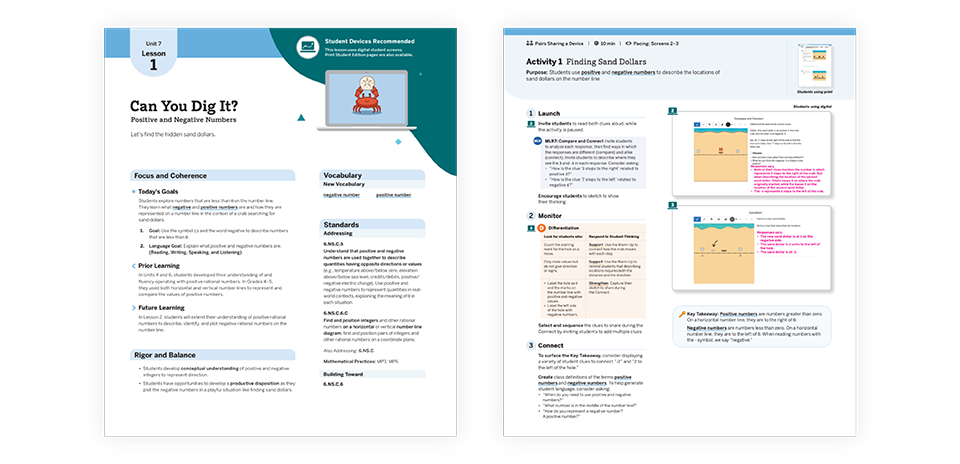

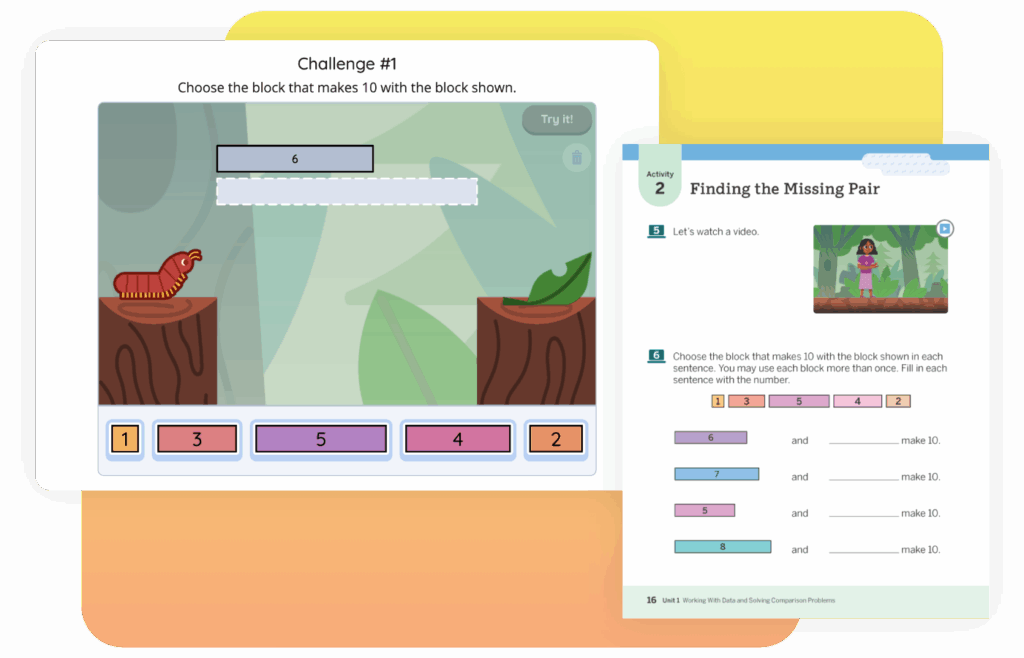

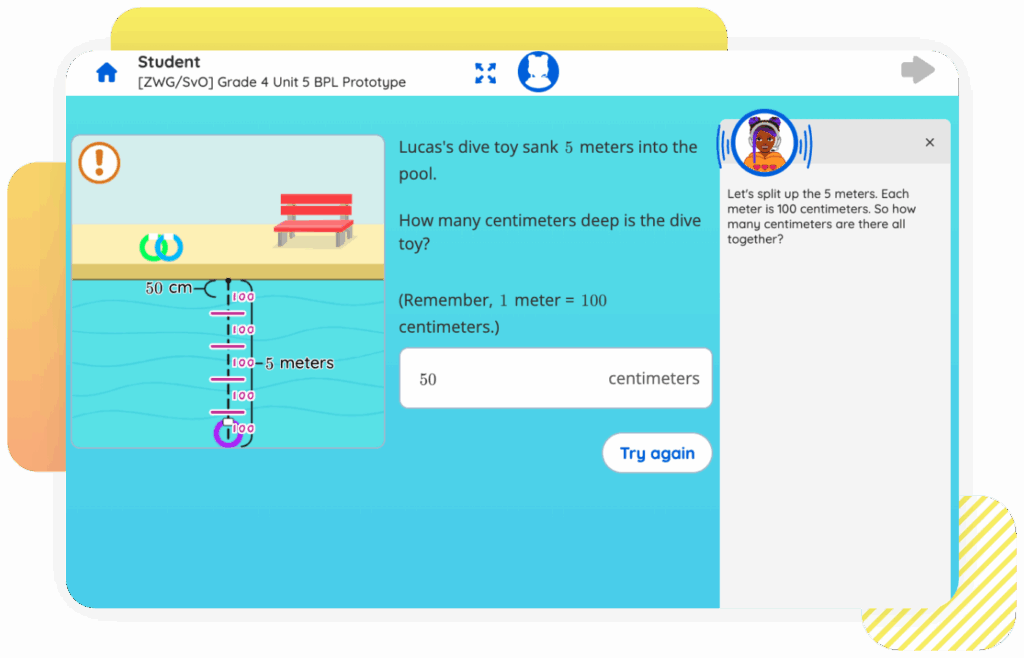

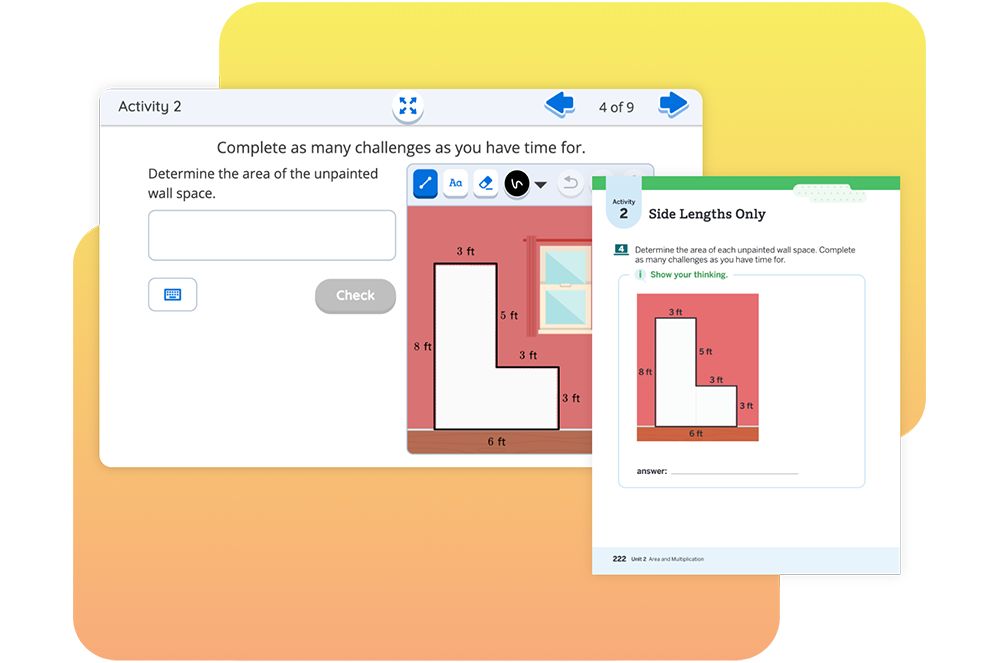

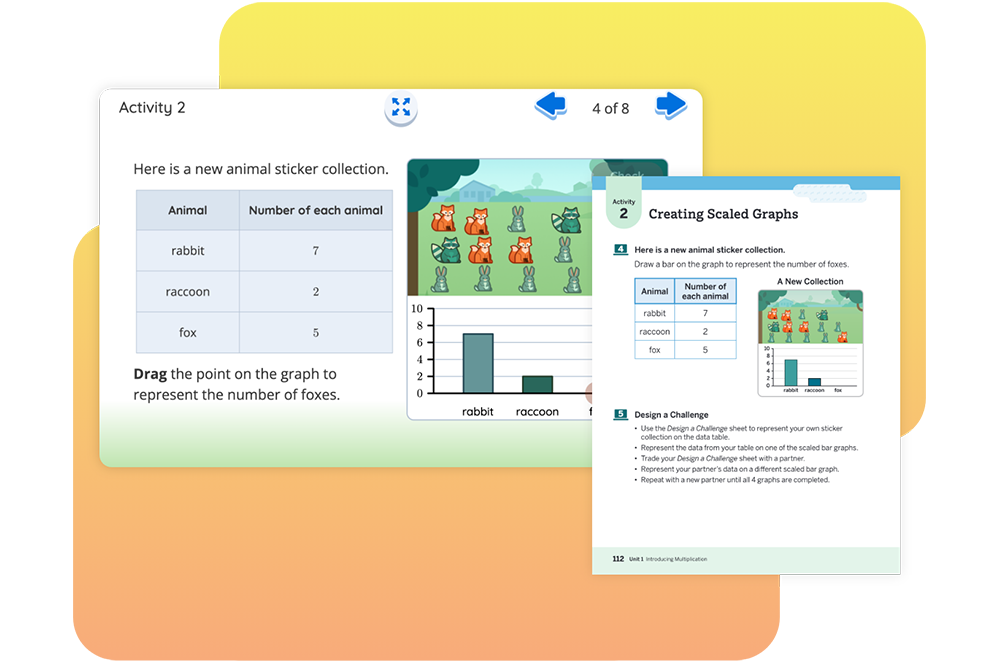

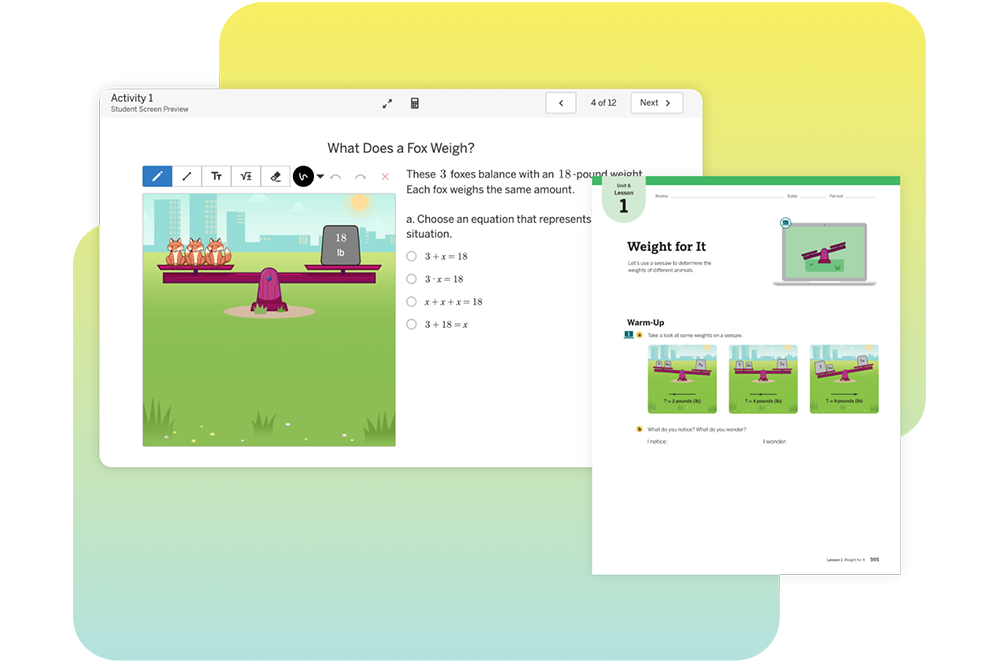

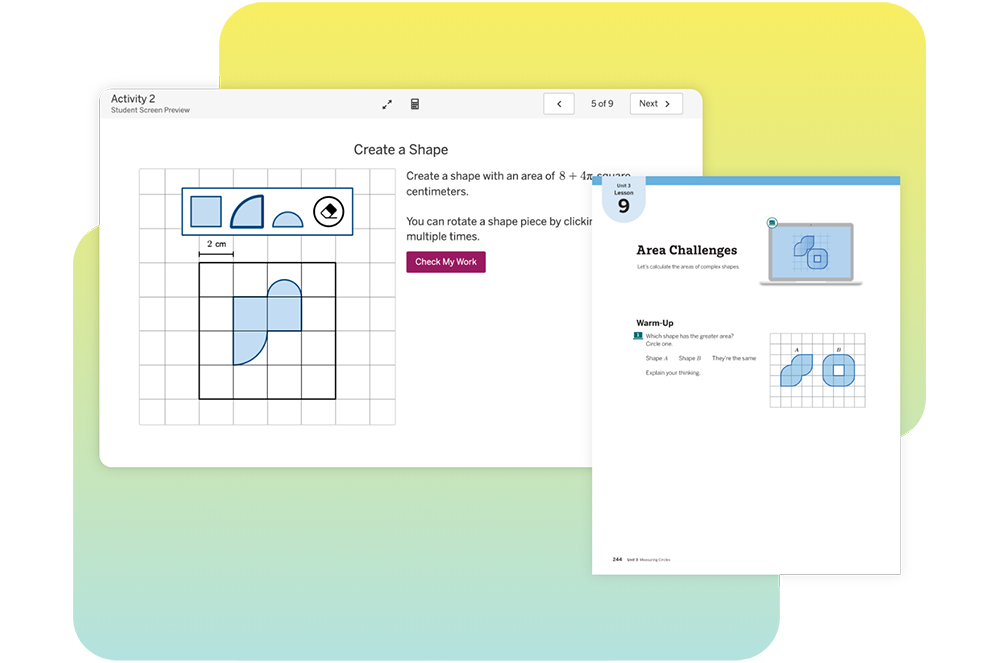

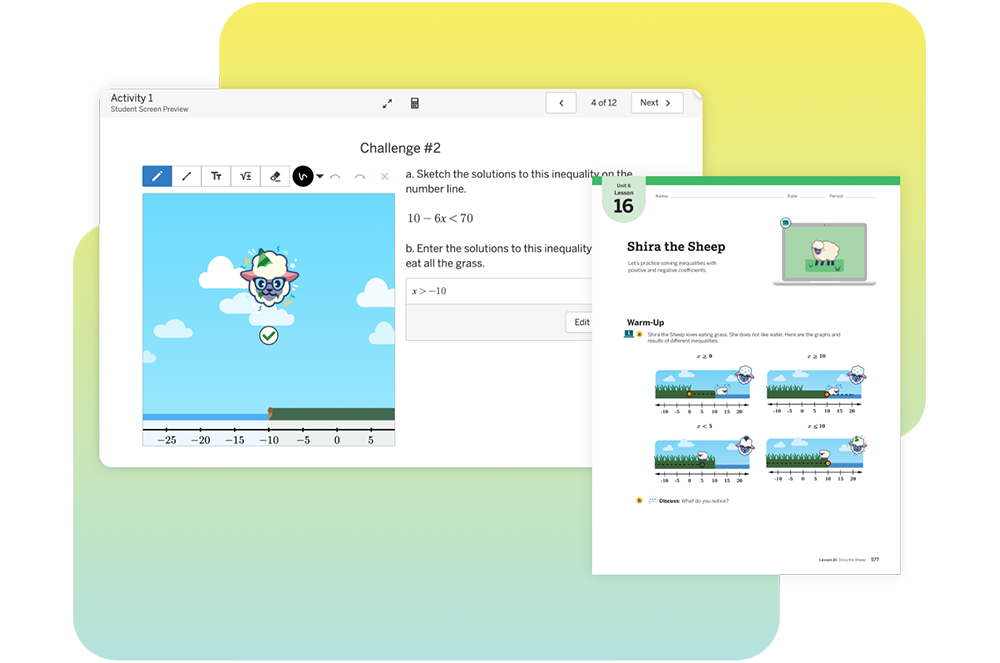

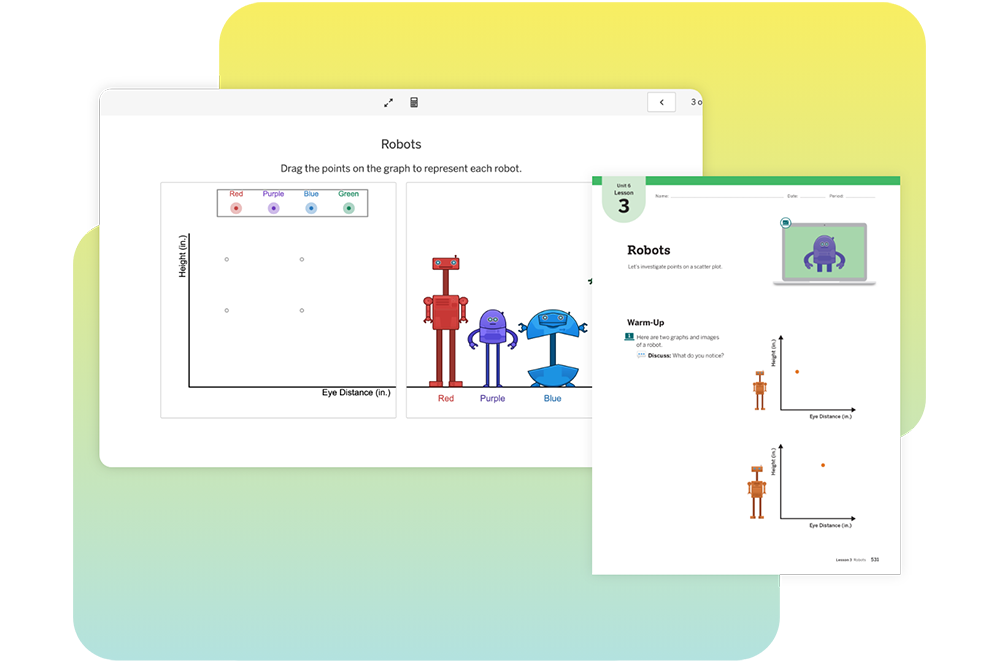

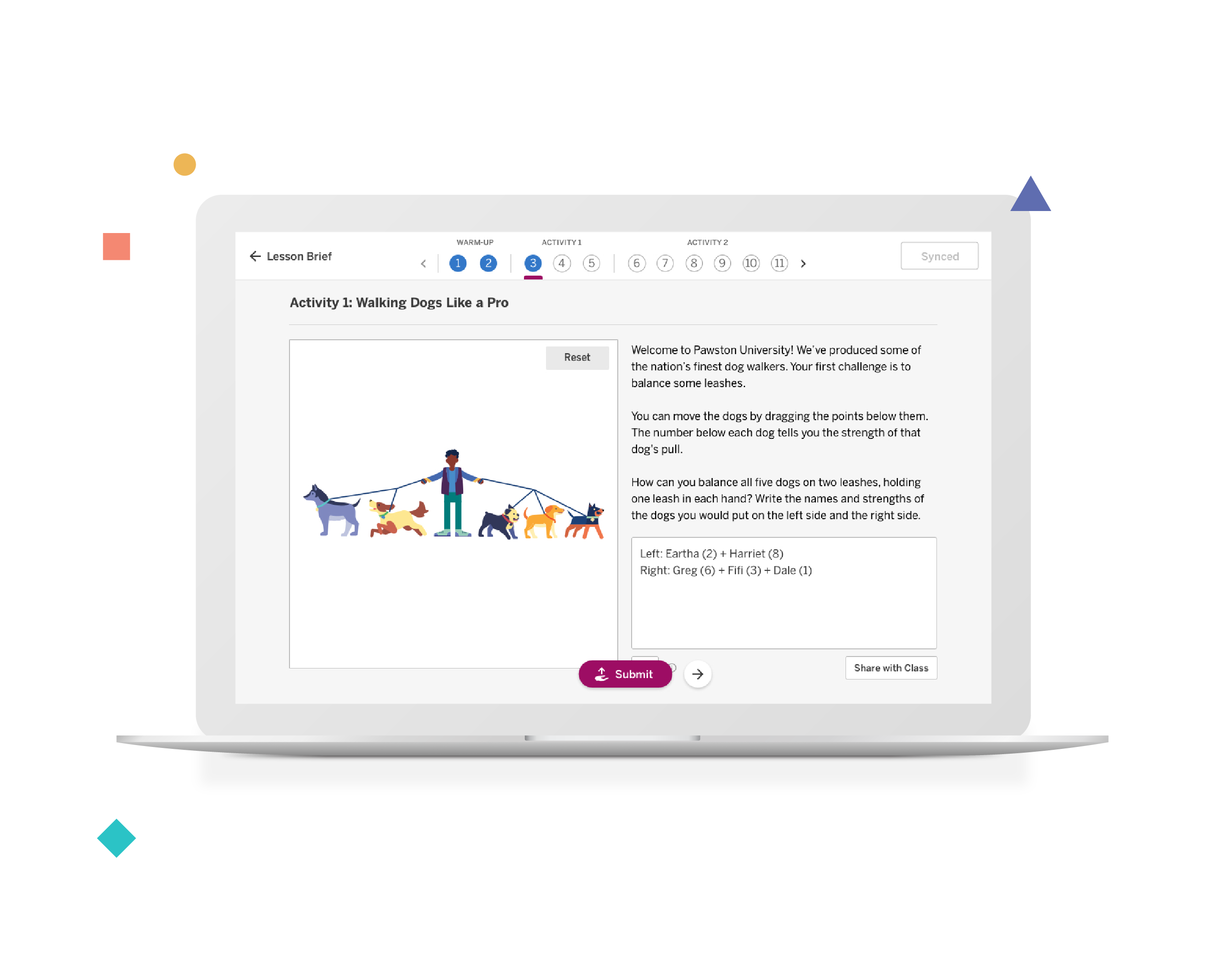

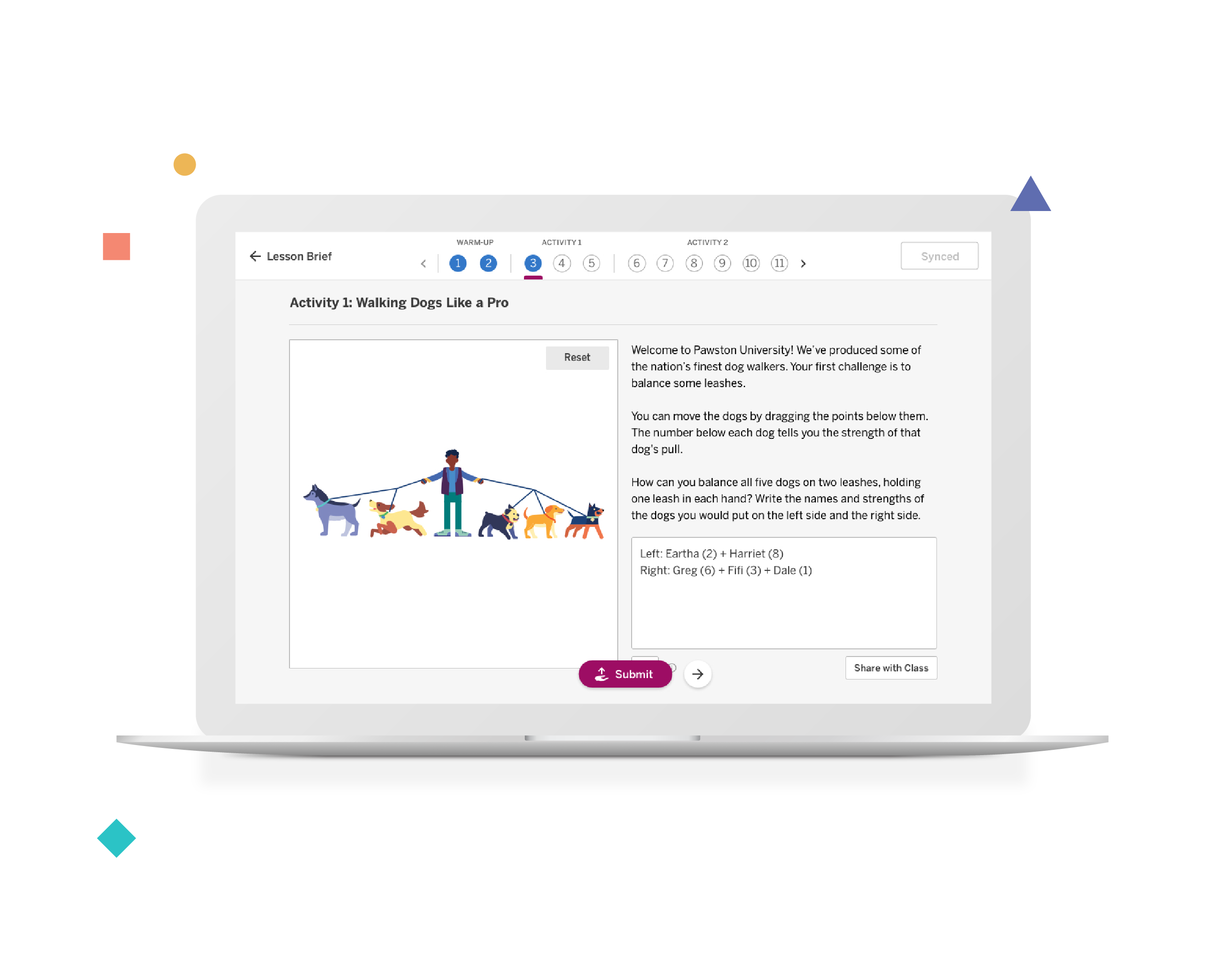

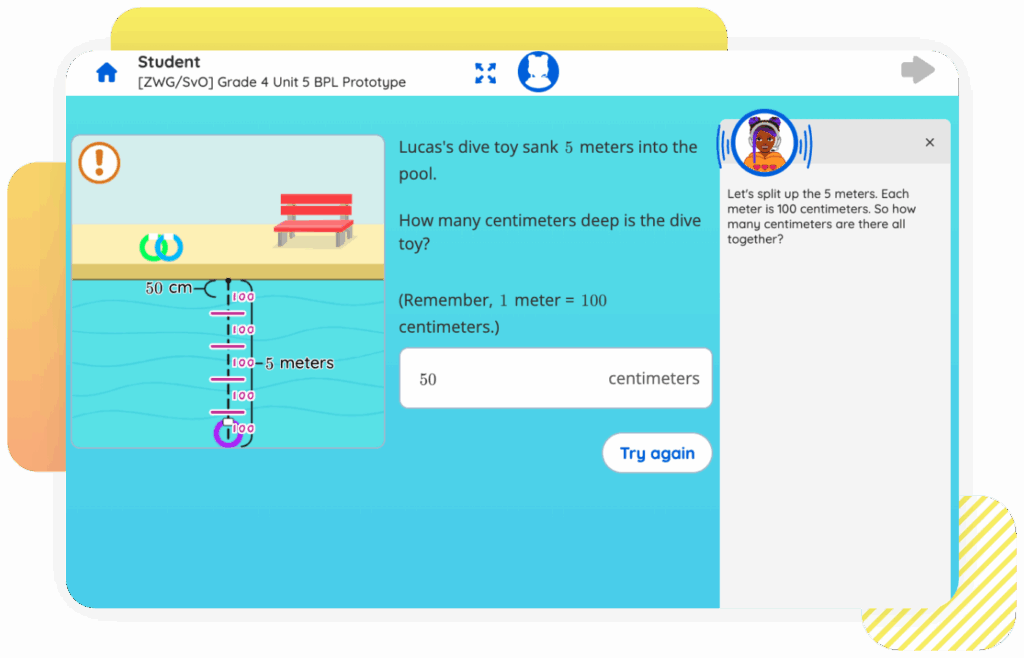

In Amplify Desmos Math, a curriculum I work on, kids generally have plenty to talk about. Our interactives stir a kid’s imagination for even the most abstract areas of math. For example, this submarine interactive stirs up a kid’s ideas about adding positive and negative integers.

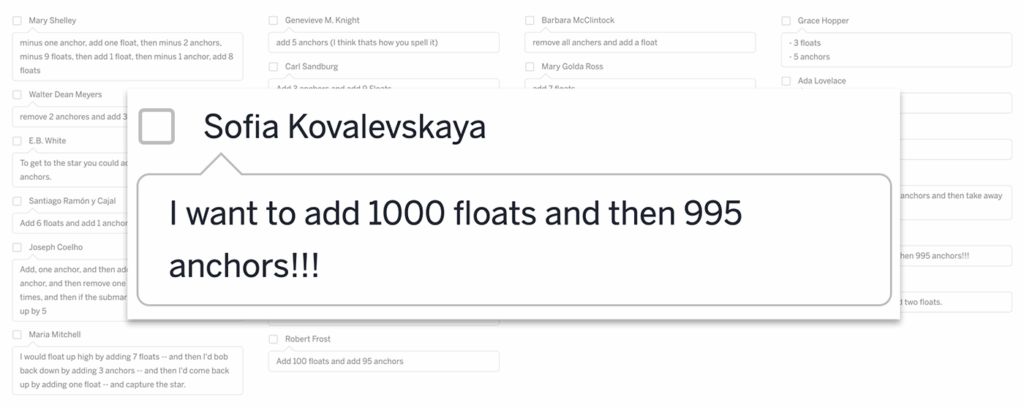

And then we ask kids, “Hey, what do you think about the star at +5? Can you come up with something that none of your classmates do?”

Let me tell you: Kids accept that challenge.

3. There is too much to talk about.

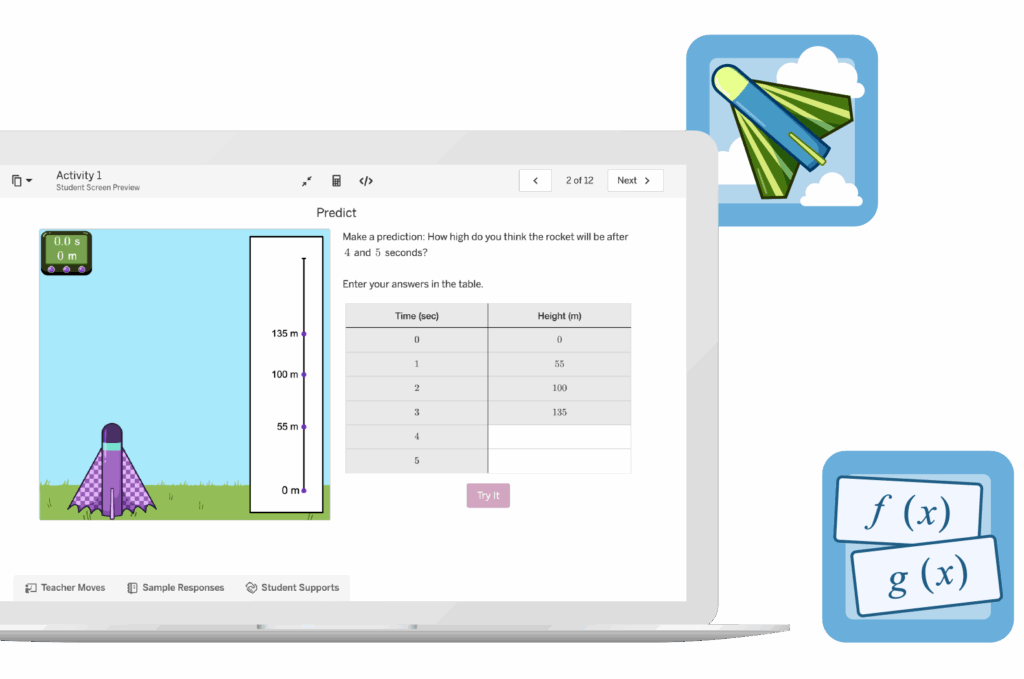

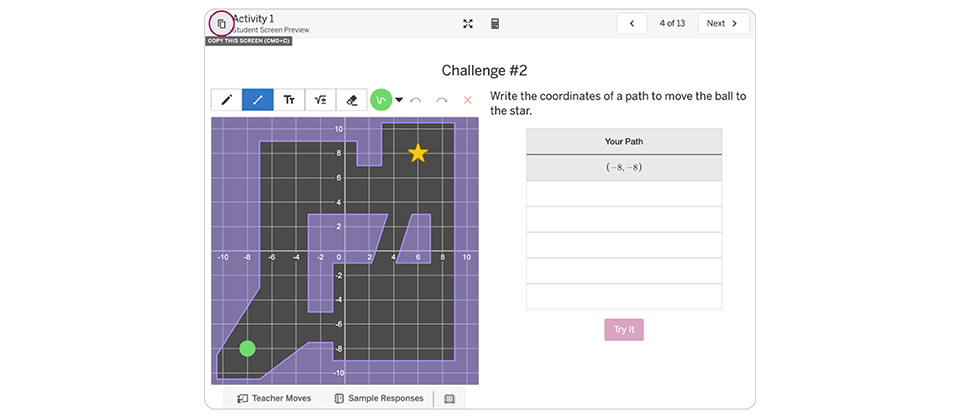

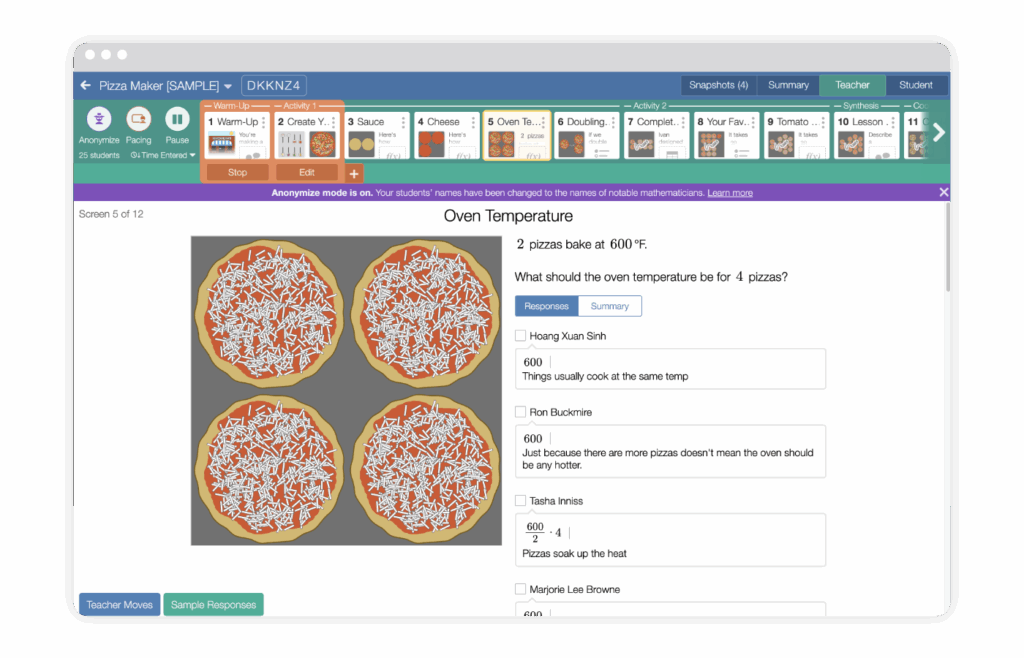

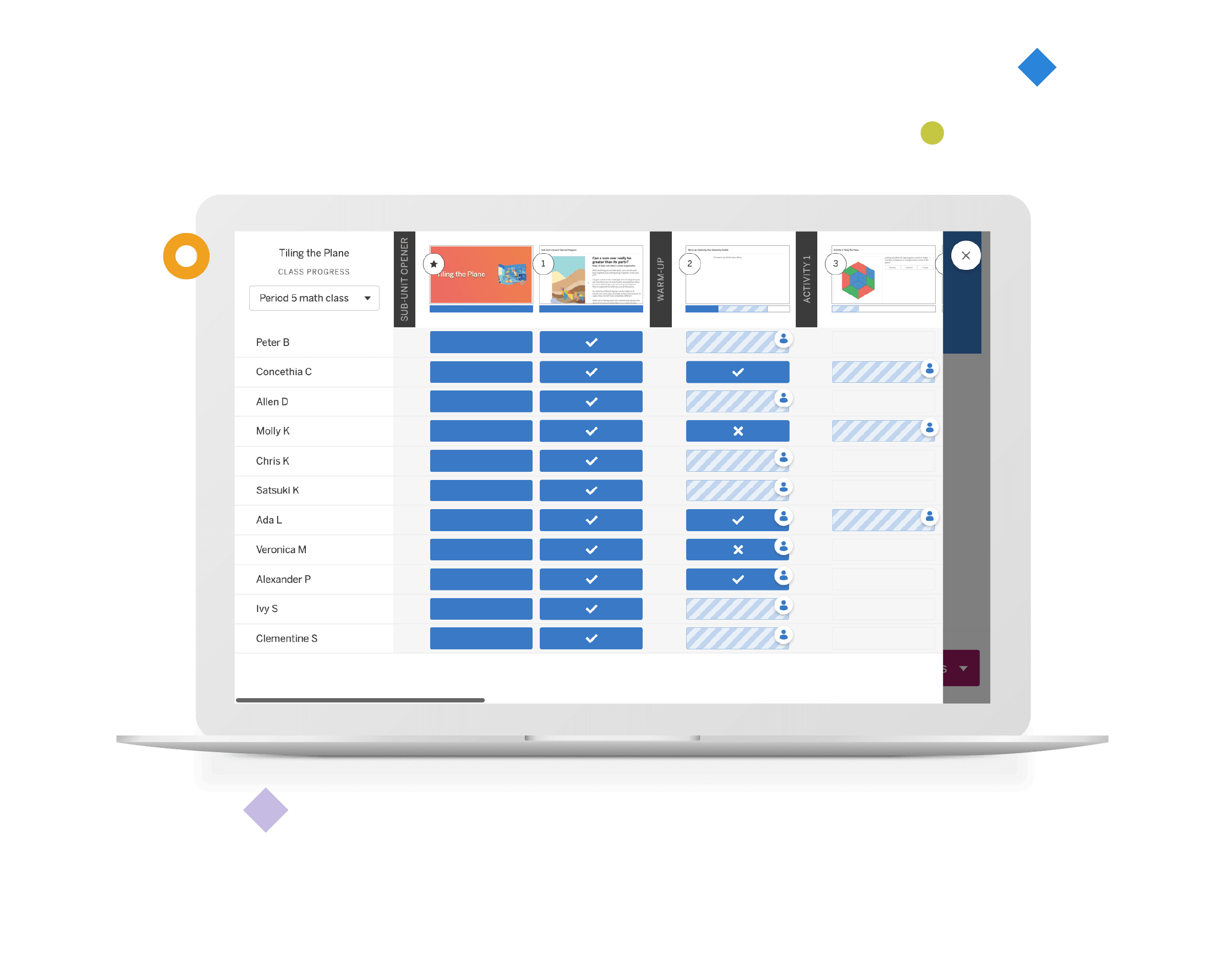

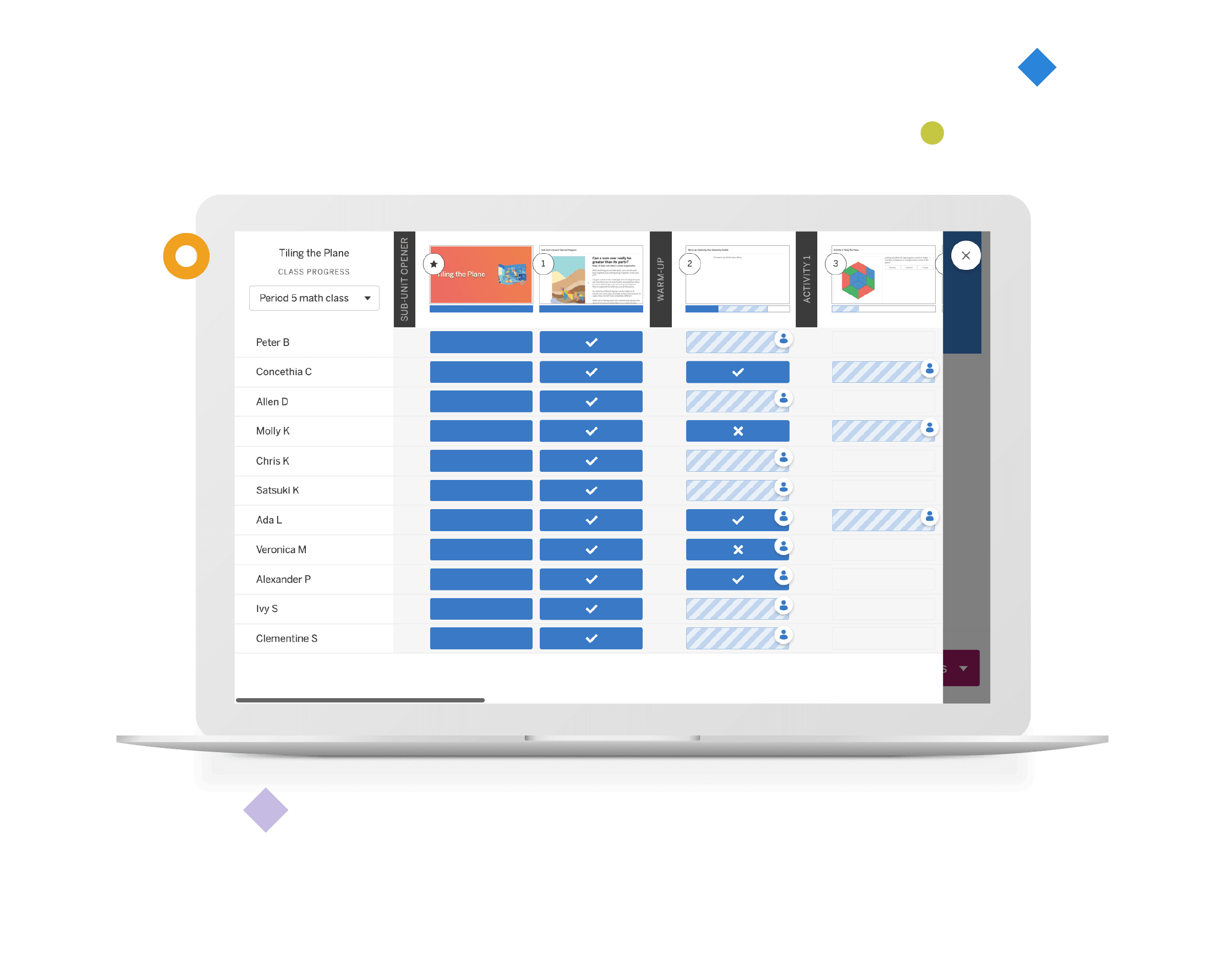

This is a good problem to have, but it’s still a problem. In the class screenshotted below, 25 students have put 300 thoughtful words in front of the teacher, every response different from every other!

Teachers now have a problem of abundance, not scarcity. They have to decide which responses to select, and why, in an environment of cognitive overload.

This is very hard work for teachers, especially novices, especially teachers who lack mathematical content knowledge, especially teachers who are hanging onto the school year by their fingernails.

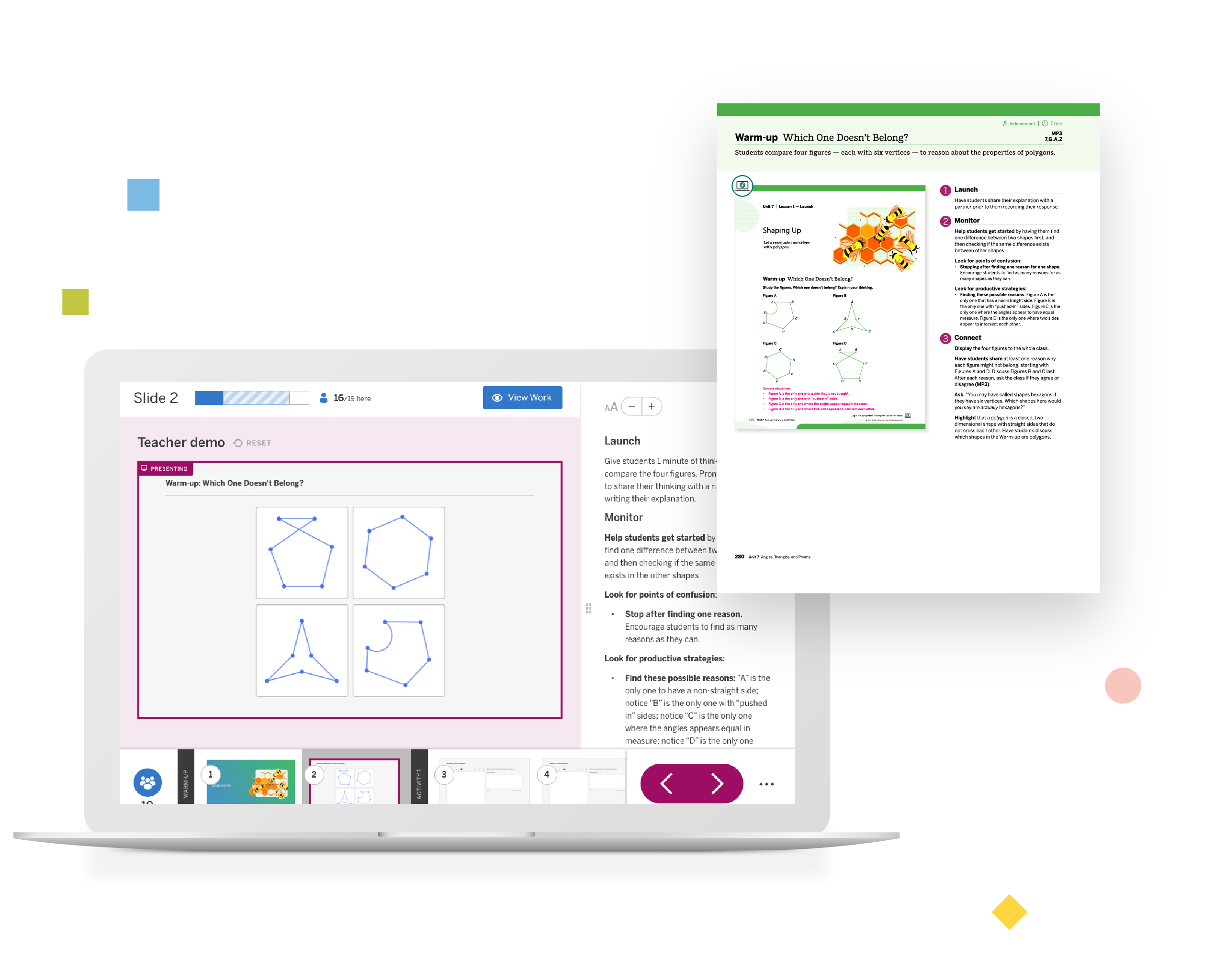

We offer teachers lots of different support for discussions throughout our curriculum—both in print and digital activities—but our new discussion support for digital activities is first-of-its-kind and best-in-class.

Discussion Moments.

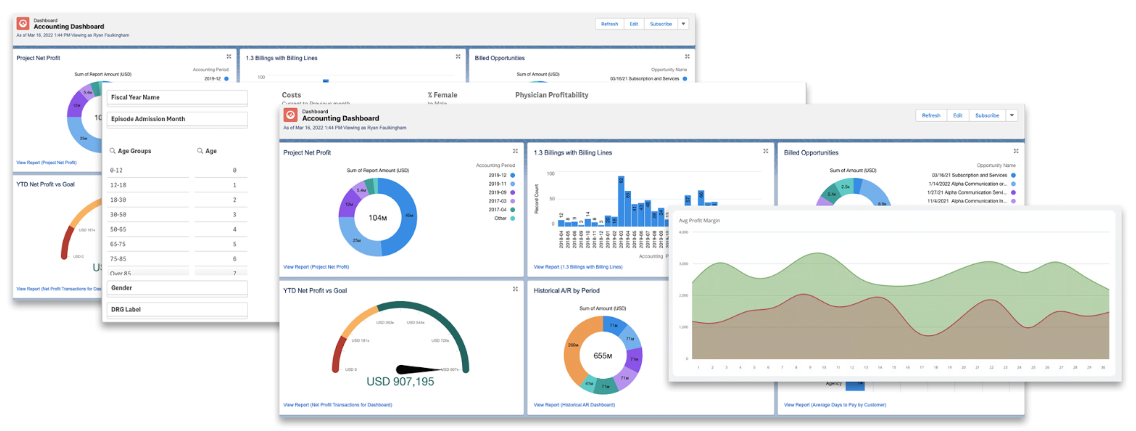

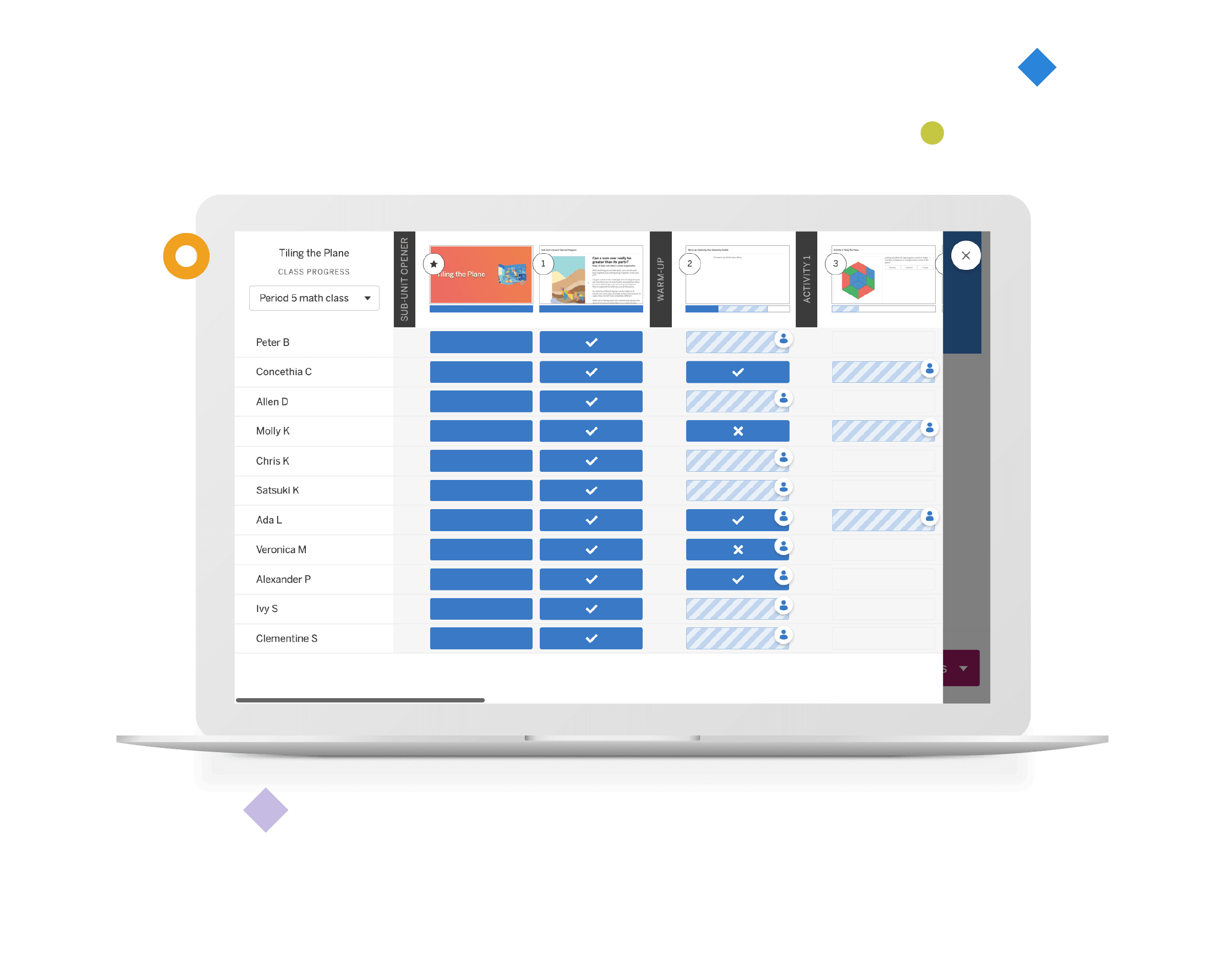

- Student responses stream into the teacher’s dashboard.

- A message appears: “Analyzing Student Responses.”

- Shortly after, the message changes: “Open Discussion Moment.”

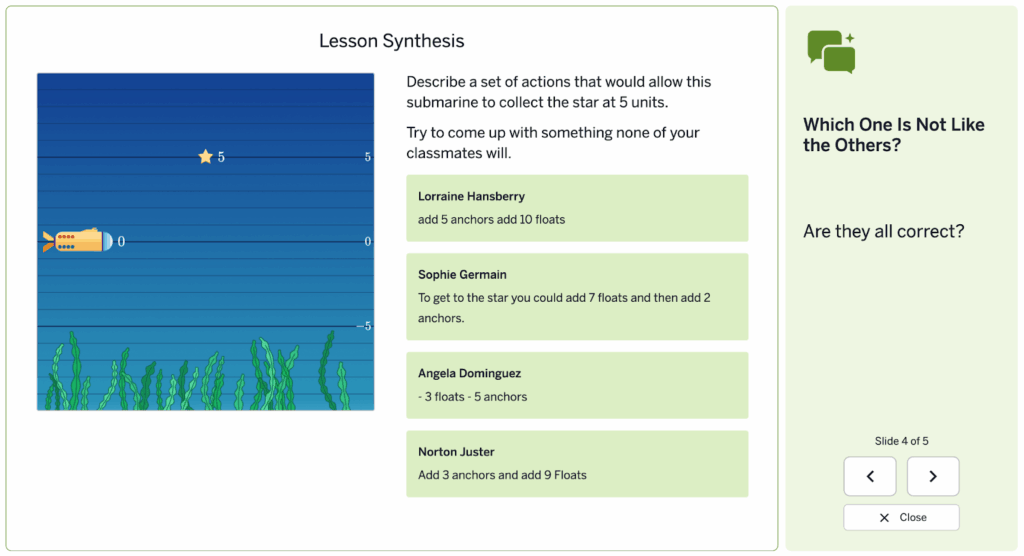

You click the message and see a classroom-ready discussion screen.

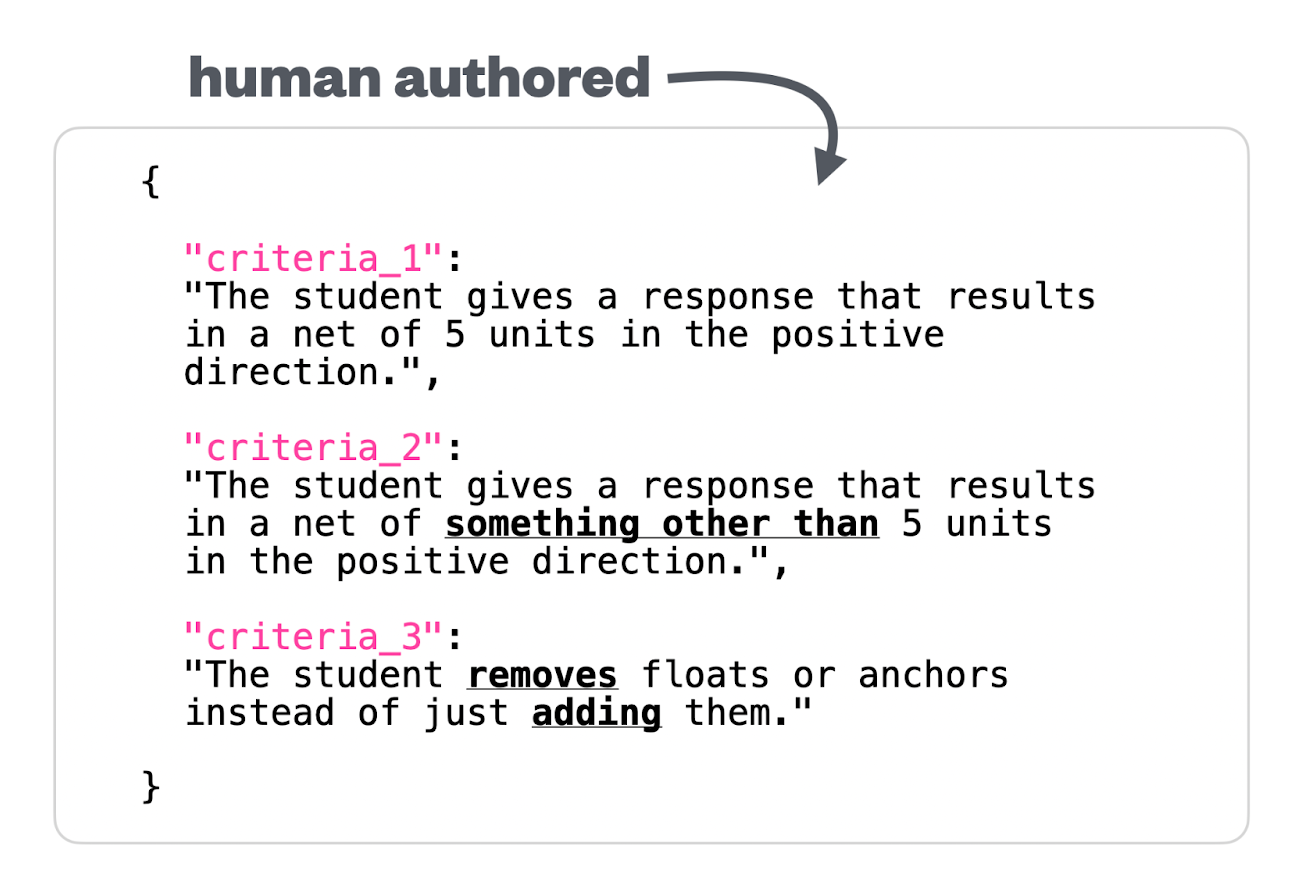

First, you see four student responses, each one authored by a student in the class, each one interesting on its own. This was not luck. Those responses were curated by a large language model at the direction of our curriculum experts. “Find three responses that capture the star in different ways,” our experts prompted the AI. “Responses that add anchors. That remove anchors. Find one response that might not capture the star.”

Next to those responses you see a question: ”Which one is not like the others?” That question feels surprisingly well-matched for this math and for those student responses. This, also, isn’t an accident. Curriculum experts made that decision.

You click the right arrow and see a suggested narration for the Discussion Moment, narration which was authored, again, by our human authors for this particular problem, to help novices learn to facilitate productive discussions in math.

That’s a “Discussion Moment.”

In the past, coaches, experts, and publishers have all asked teachers to . . .

- Select and sequence student responses.

- Construct a student-facing discussion resource.

- Lead the conversation.

Now we are asking teachers to . . .

- Lead the conversation.

In our experience, computers do quite well with the first two jobs while teachers obliterate computers at the work of leading a conversation, at connecting student ideas, at asking one kid what they think of another kid’s idea, at pulling ideas out of a kid who maybe doesn’t think they have ideas to offer. Discussion Moments delegate to humans and computers the best work for each of them.

Discussion Moments are different.

Lots of edtech companies are putting AI to work in lots of different ways. Discussion Moments are unique.

First, they’re designed to work through rather than around the teacher, during class rather than outside of class. They’re designed to support social interactions between students and teachers in the moment of instruction. This is the action.

Second, this is a classroom-ready resource. So many AI applications just output a ChatGPT-style resource. Lots of text. Several main bullets. Lots of sub-bullets. An emoji or two. And I am very sorry, but they are not useful in class. The teacher has to read all of that text, copy and paste and edit it, and then construct the student-facing resource all in the middle of class. That’s fantasyland, folks. At Amplify, we have, instead, created a one-click, classroom-ready resource.

Third, we’ve fortified these digital Discussion Moments with gallons of human expertise. Since December, I’ve worked with several of our curriculum experts—Casey Nelson, Brian Kam, and Tom Snarsky—and for every problem across several units of middle school math, they:

- Reviewed thousands of student responses to each problem.

- Identified thematic trends in the student responses.

- Decided whether or not those themes demand a discussion.

- Decided which of several discussion frames would be most appropriate, given those themes.

- Wrote an AI prompt specific to each problem to increase the odds that the large language model will curate useful student responses.

Most edtech companies would prefer to let AI lead this process from end to end, using the same prompt for every problem, even at the cost of the teacher and student experience. Meanwhile, we only ask AI to execute instructions and construct a resource. The nature of those instructions, the type of resource, and how it’s used—that is all determined by different humans and their expertise.

What do teachers and administrators think?

I ran a small-scale pilot of this feature last spring and kicked off a larger-scale pilot last week. A couple hundred teachers overall. I have never had an easier time recruiting teachers for a project than with this one. Every district math curriculum lead knows how challenging it is for teachers to lead discussions, and every one I asked was eager to support.

Two other examples of Discussion Moments.

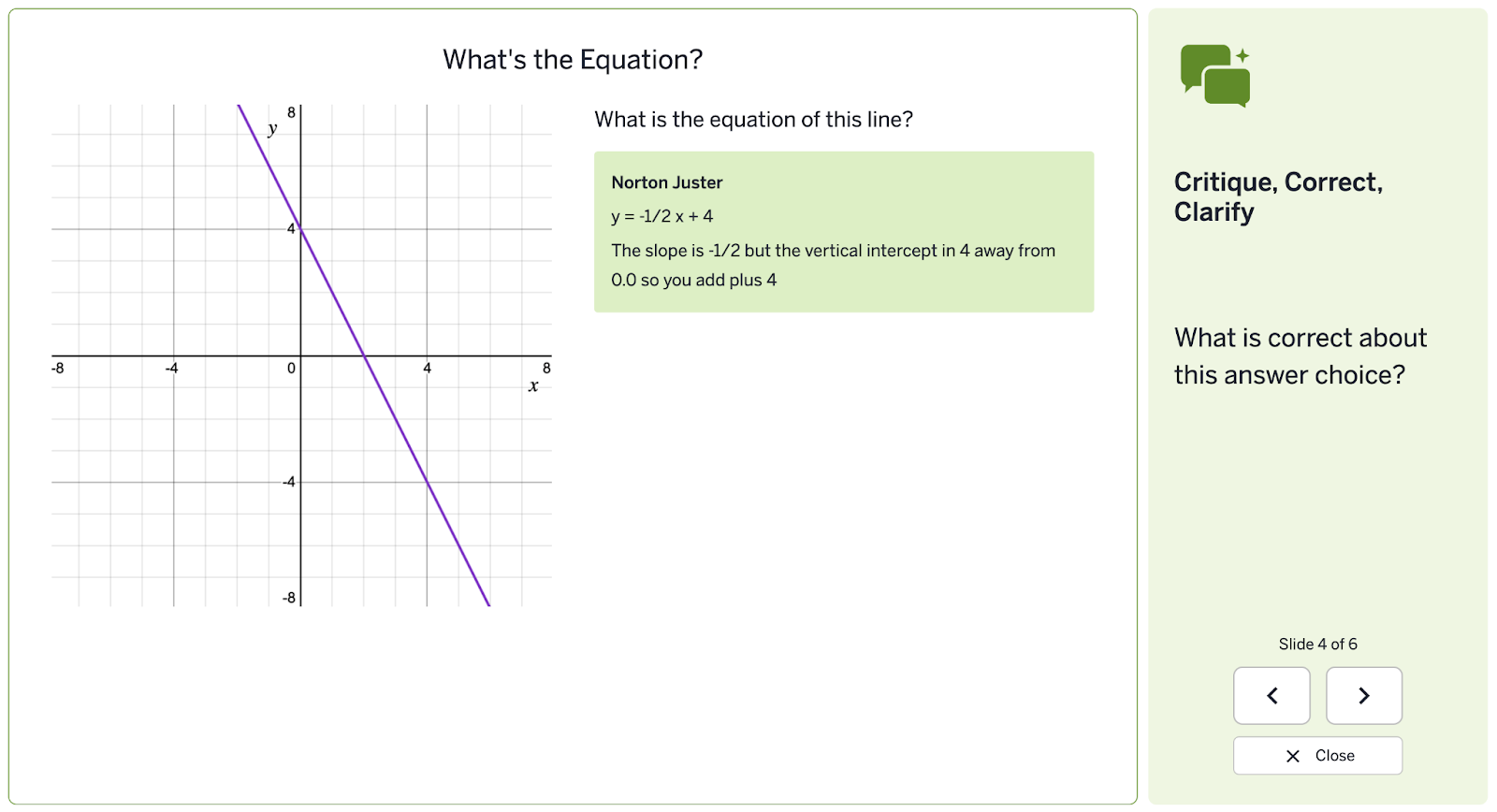

Compare and Connect. We asked a large language model to locate responses that have one of a couple of important features but ideally not both. Then we constructed a Discussion Moment asking students to write a response that combines the best of both answers.

Critique, Correct, Clarify. Our curriculum authors noticed a frequent incorrect answer to a question. We told the LLM to watch out for it and frame it in a Discussion Moment where the class is asked to find value in the wrong answer before correcting it. Try to imagine what it does to a kid to hear their incorrect answer described as valuable.

Wait—don’t you hate AI?

I get why you might ask me that, but no. I think generative AI is perhaps the most overrated education technology of my lifetime; I don’t think the chatbot tutors or lessonslop generators are going to transform K–12 education. But I do think generative AI is neat. And look, I have tried to support discussion work with K–12 teachers for the last ten years in other ways, too. I have run in-person and remote PD. I have written math lessons and teacher supports for those lessons. I have sent nifty little customized email sequences tailored to teacher usage. None of those supports have been as promising as AI is here. None of them has moved the needle like Discussion Moments because none of them has been able to meet teachers in their moment of need, at the point of use.

That’s it. You can find Discussion Moments in Amplify Desmos Math next school year.

Other publishers say they have “Desmos.” What’s the difference between what Amplify has and what they have?

If you’ve been in the math world for a while, you know the name Desmos. It’s synonymous with free dynamic math tools.

And lately, you’ve probably also been hearing about Amplify and Desmos together. But other publishers also say they have Desmos, so what’s the deal?

Let’s clear it up.

The most important thing to know is that, back in 2022, the original Desmos split into two separate parts. Think of them like a calculators and other tools part and a classroom activities and curriculum part.

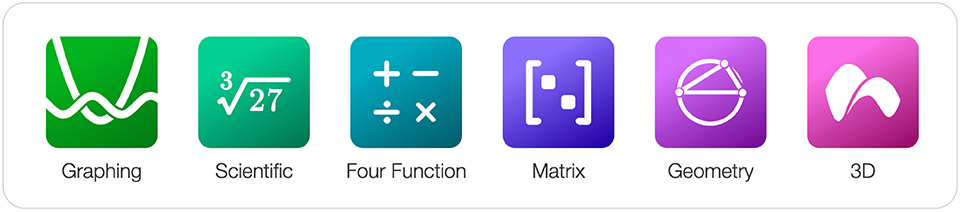

The tools part: Desmos Studio

This is the Desmos you first fell in love with.

What it is: Desmos Studio is the name of the company that builds and maintains the powerful, free Desmos calculators. This is an independent Public Benefit Corporation, and can be found at www.desmos.com. That team builds and maintains a collection of free math tools:

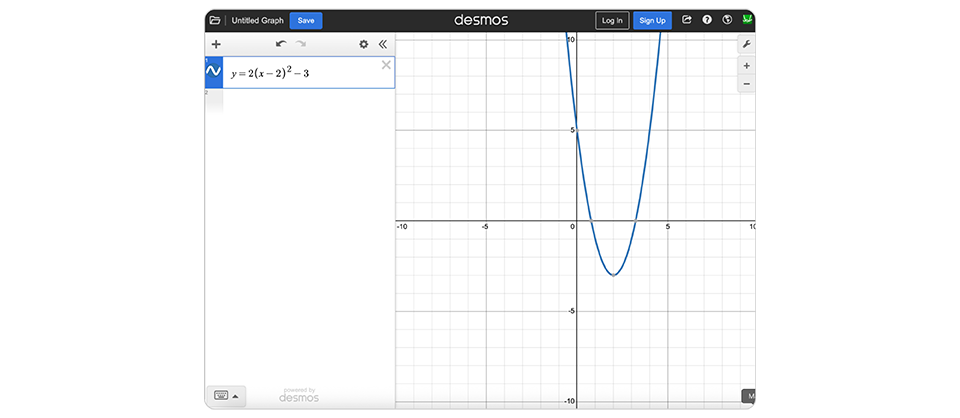

What it’s for: This is your go-to for exploration, demonstrations, and “What if I change this?” moments. It’s the blank canvas you use on your smartboard or the tool your students use for homework.

The bottom line: The calculators are run by an independent company called Desmos Studio PBC. You can find their tools for free at their website, desmos.com; on state tests; and in curriculum programs (including ours).

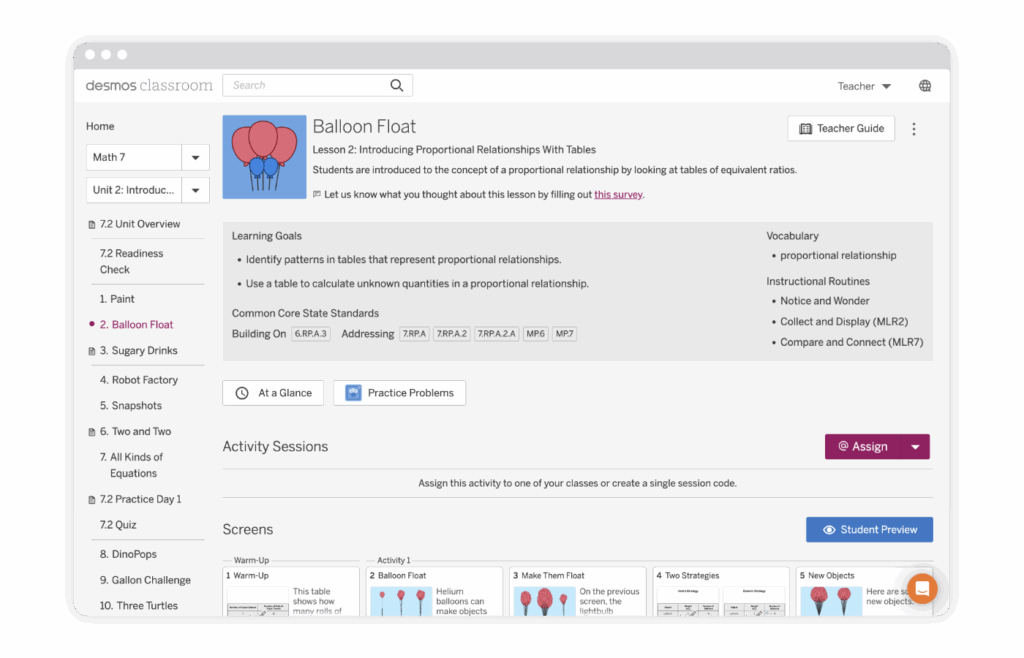

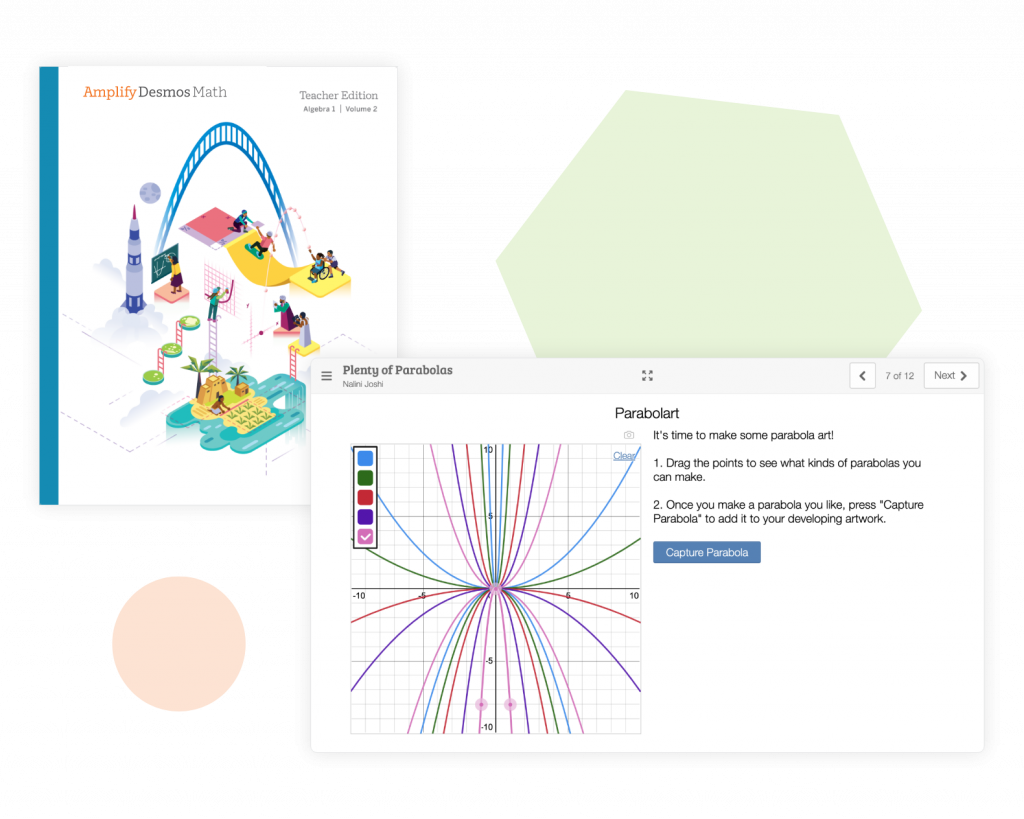

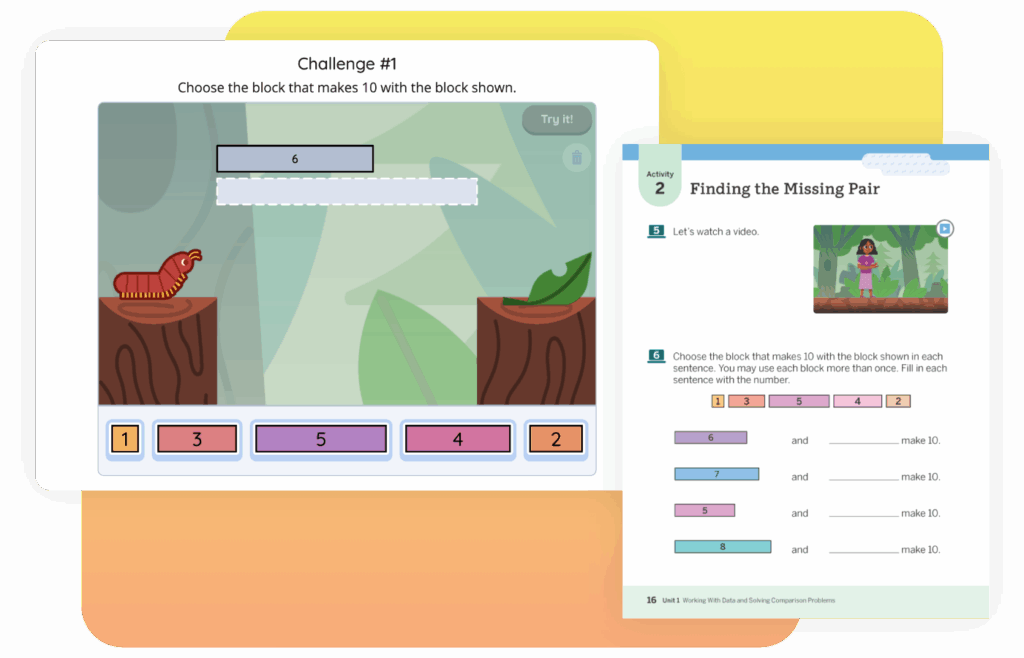

The lessons: Amplify Classroom & Amplify Desmos Math

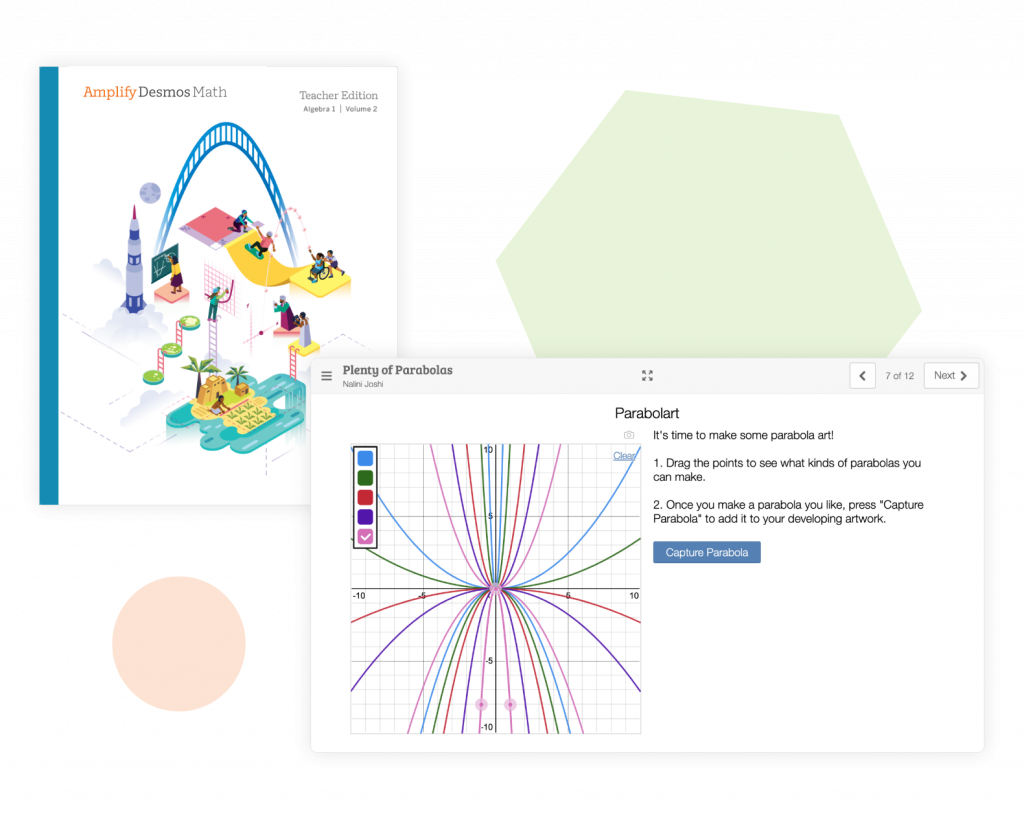

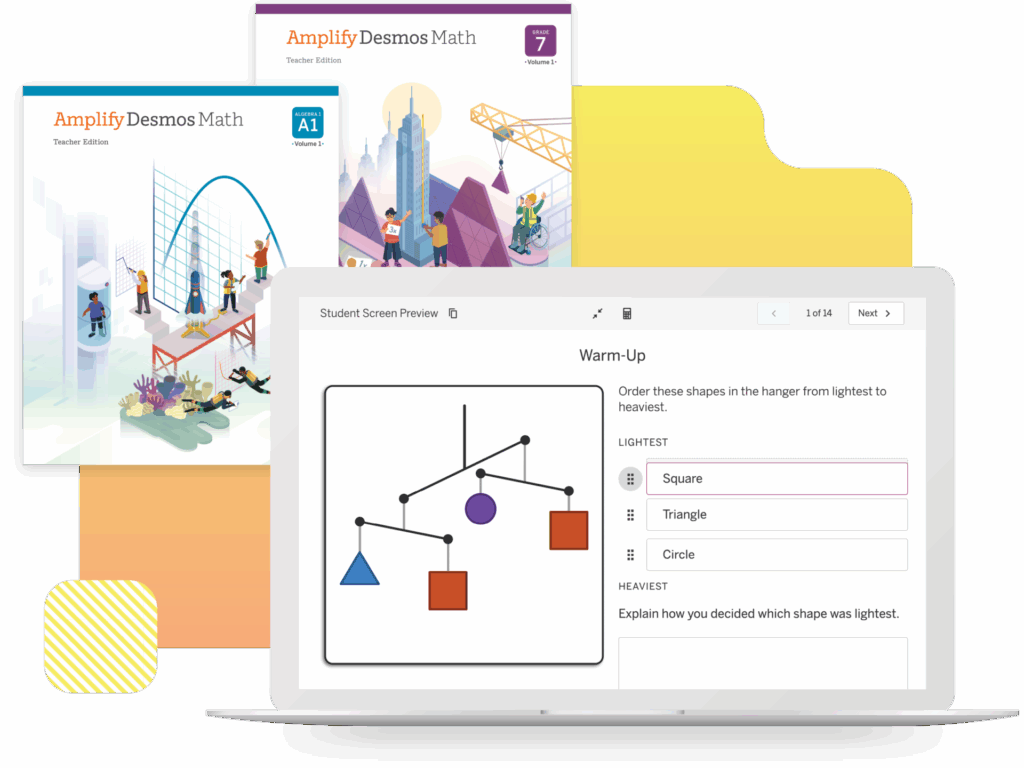

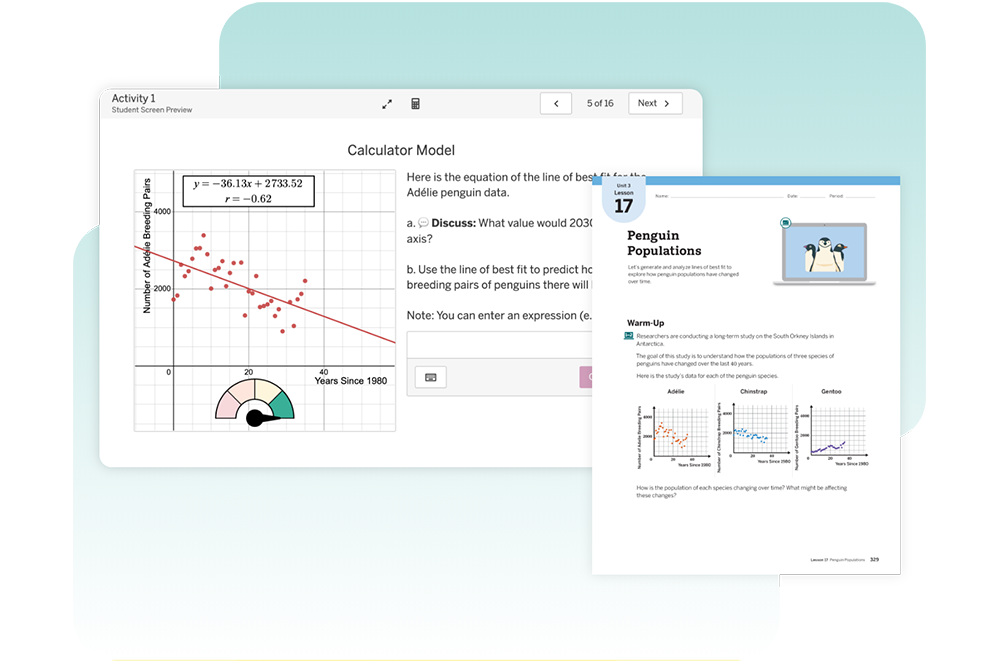

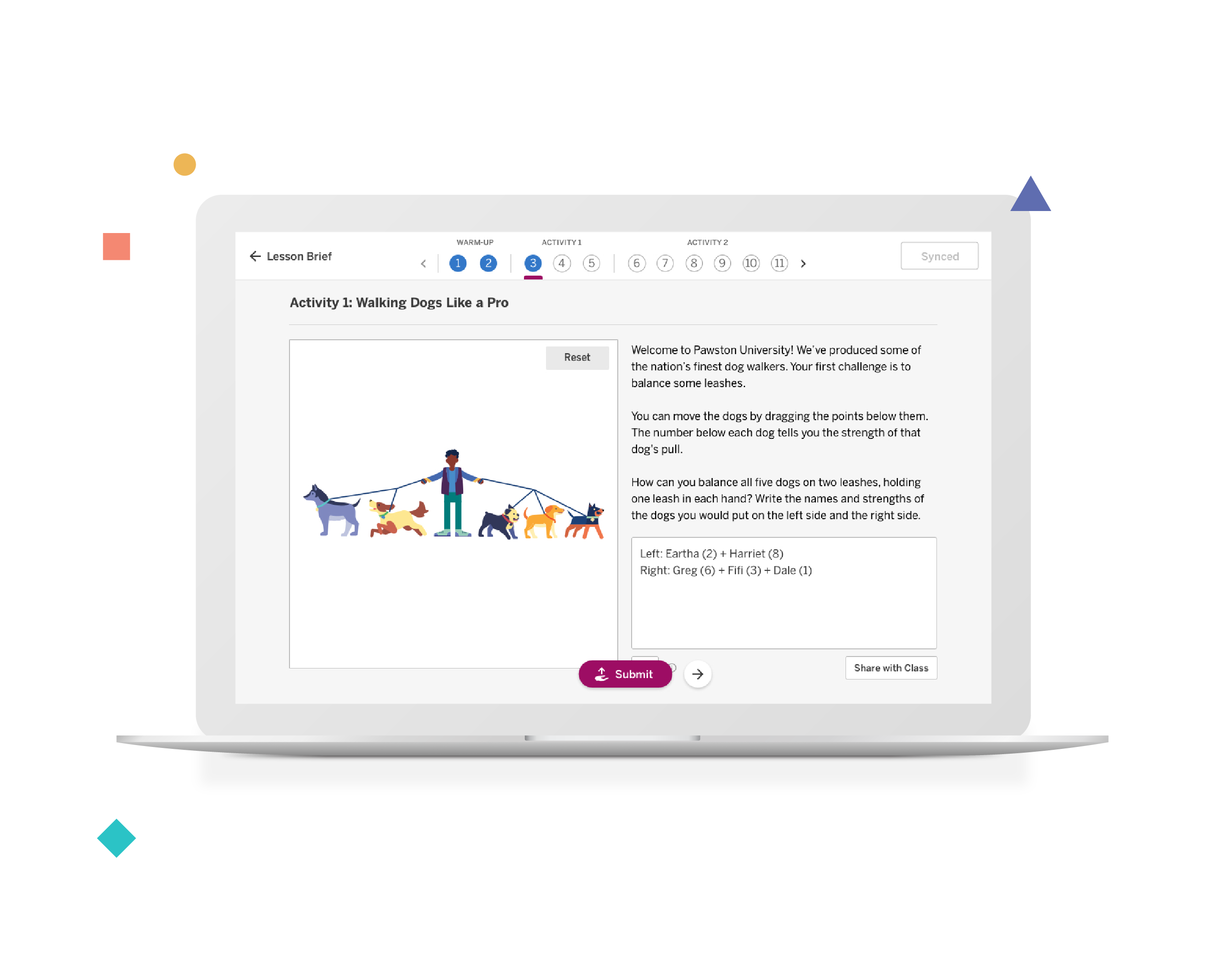

What it is: In 2023, Amplify acquired the Desmos instructional platform (then called Desmos Classroom, now called Amplify Classroom) as well as their math curriculum for grades 6–8 and the teams that built those resources. We had already been working on our own math curriculum, decided to combine forces with the Desmos curriculum team, and created Amplify Desmos Math, now available for grades K–12.

When other publishers may talk about having “Desmos,” what they mean is they license the calculators and Geometry tool from Desmos Studio.

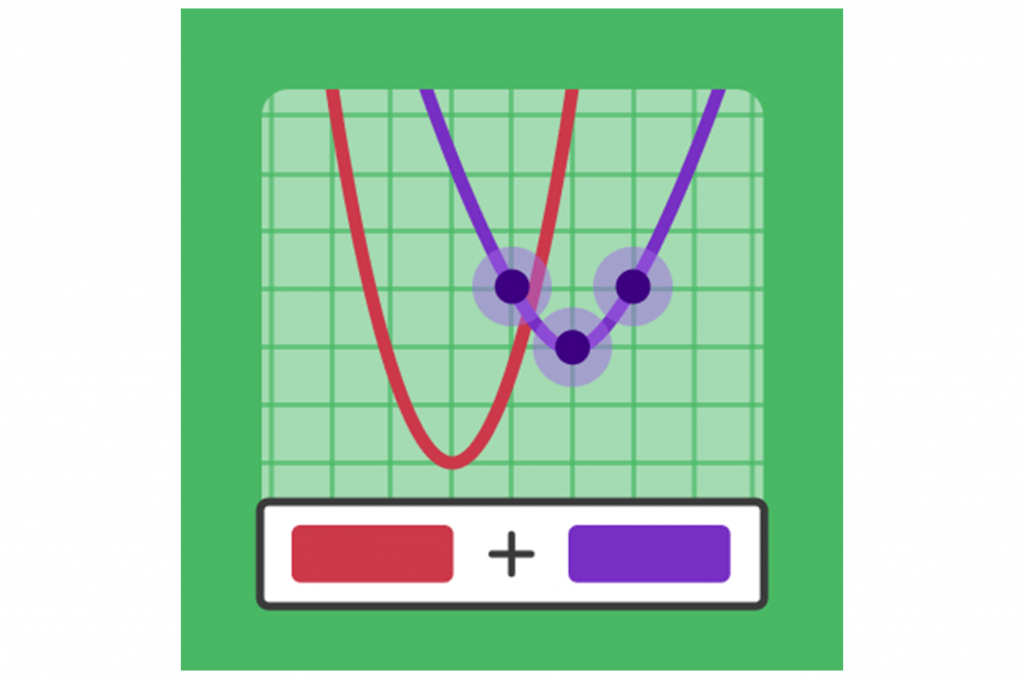

What it’s for: Amplify has these tools, too, but we also have the Activity Builder, which integrates these tools much more deeply than is possible with other Desmos Studio partnerships. We take this powerful Desmos technology and layer instruction, student collaboration, and dynamic teaching tools on top, creating classrooms that buzz with excitement and learning.

What’s available for free:

- The “Desmos activities” platform (you might know it from teacher.desmos.com), now Amplify Classroom. This is where you can find hundreds of free lessons and activities. You can also use the Activity Builder tool to create your own custom activities from scratch.

- The beloved, pre-built “Activity Builder” activities like “Marbleslides” and more are still available for free on Amplify Classroom.

The bottom line: Educators can still use the vast library of free activities and build their own on Amplify Classroom. This is not changing.

The core curriculum: Amplify Desmos Math

This is the new, comprehensive curriculum available to districts and schools.

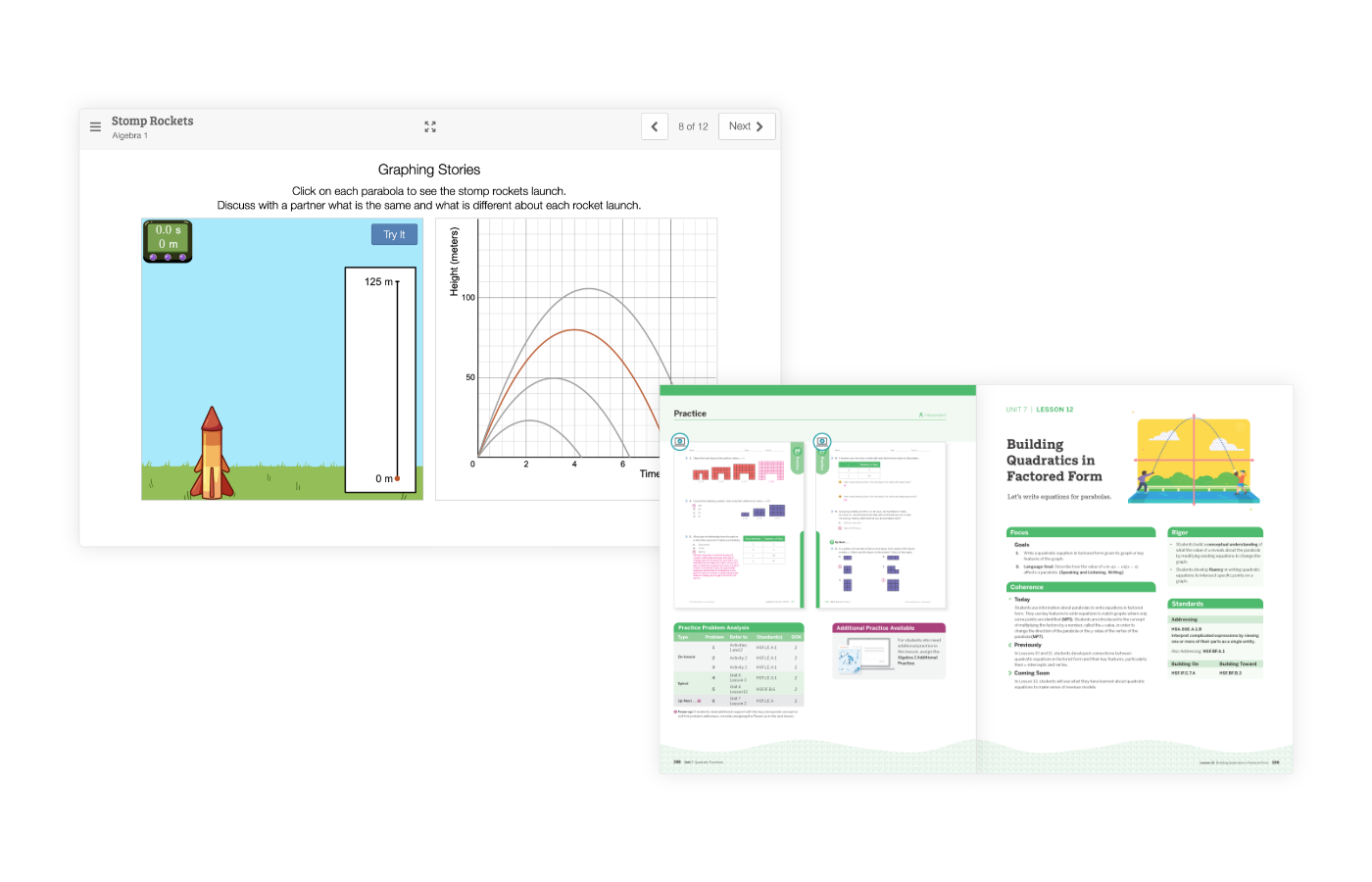

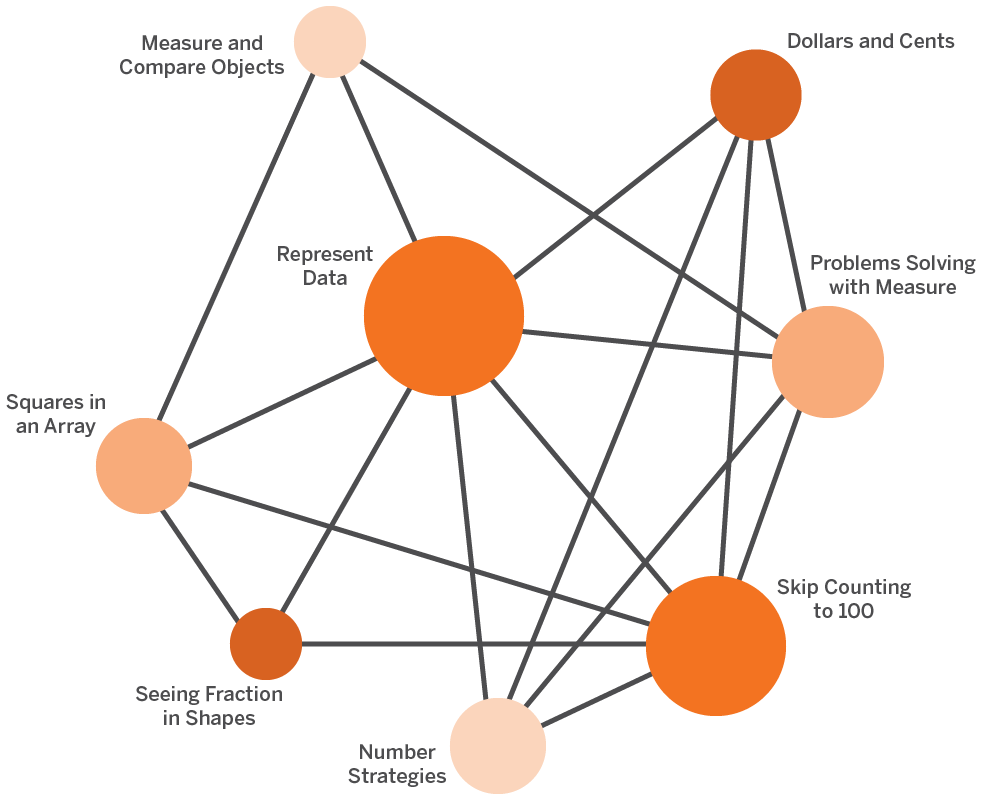

What it is: This is a full core math curriculum for grades K–12 that Amplify has built in collaboration with the Desmos curriculum team that joined us a few years ago. It uses the Desmos instructional philosophy and tools as its backbone, but it’s much more than a collection of activities.

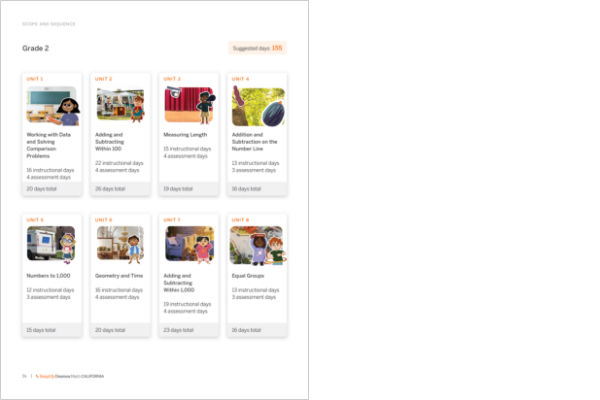

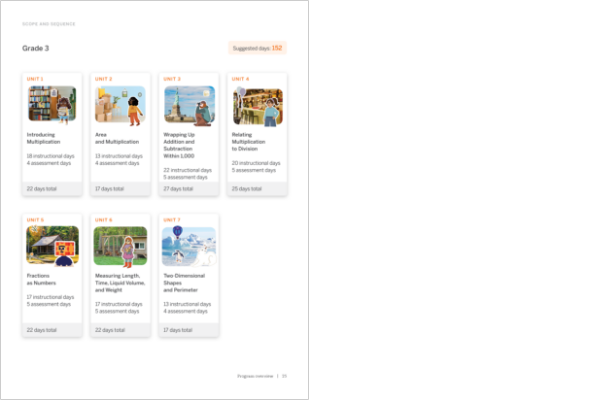

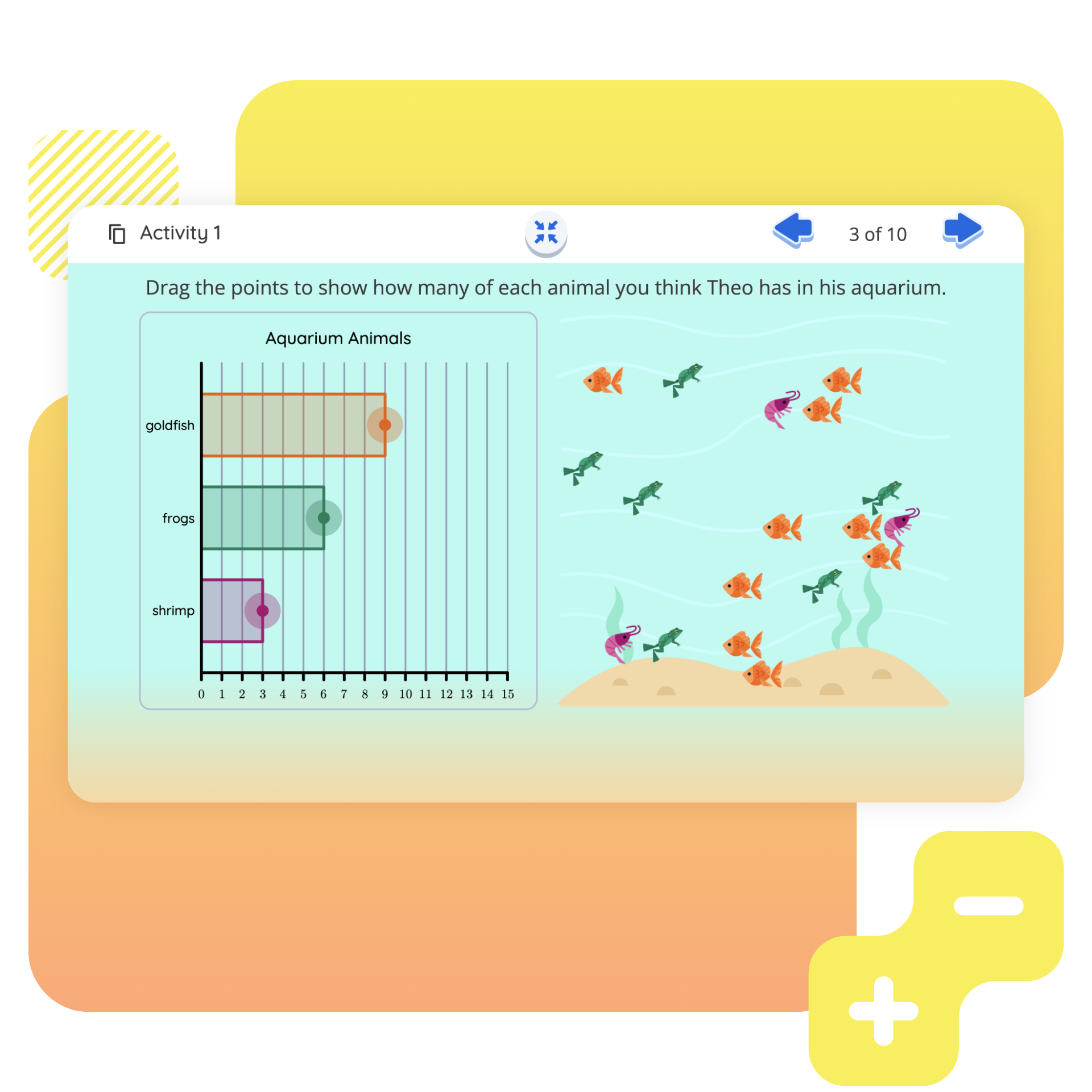

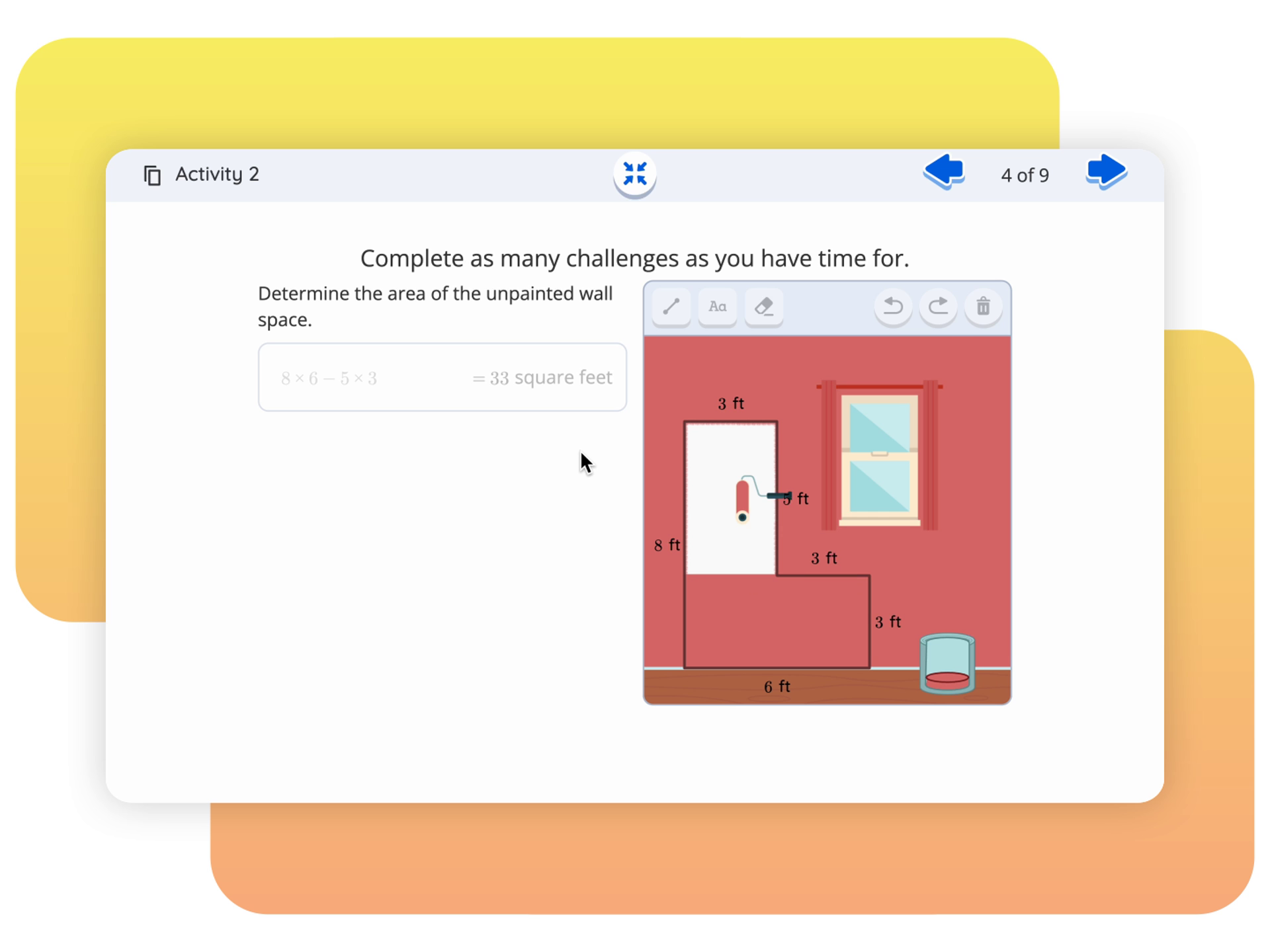

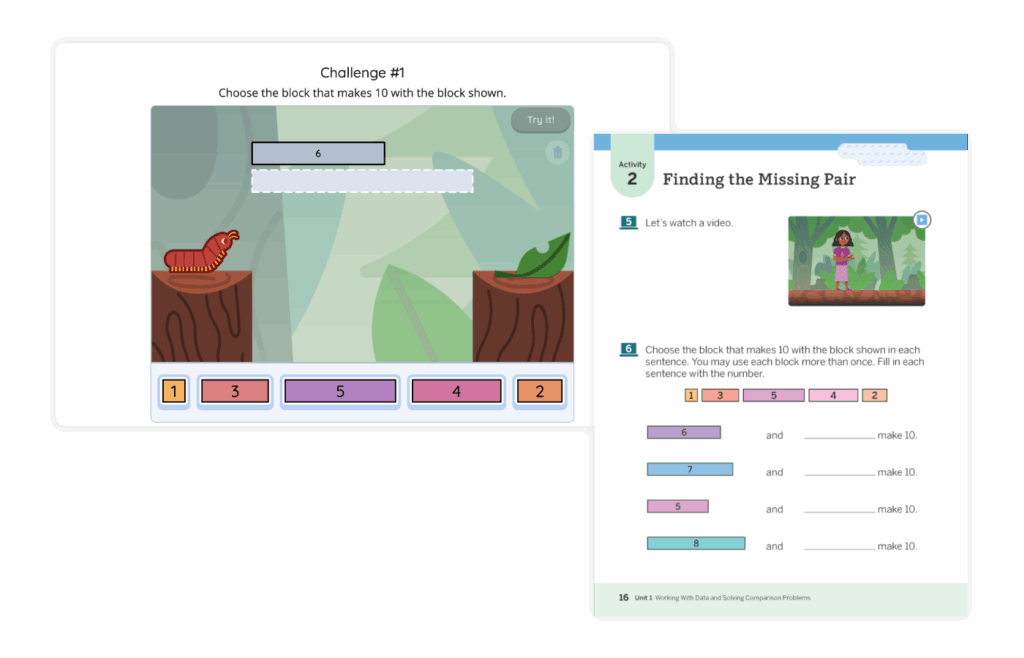

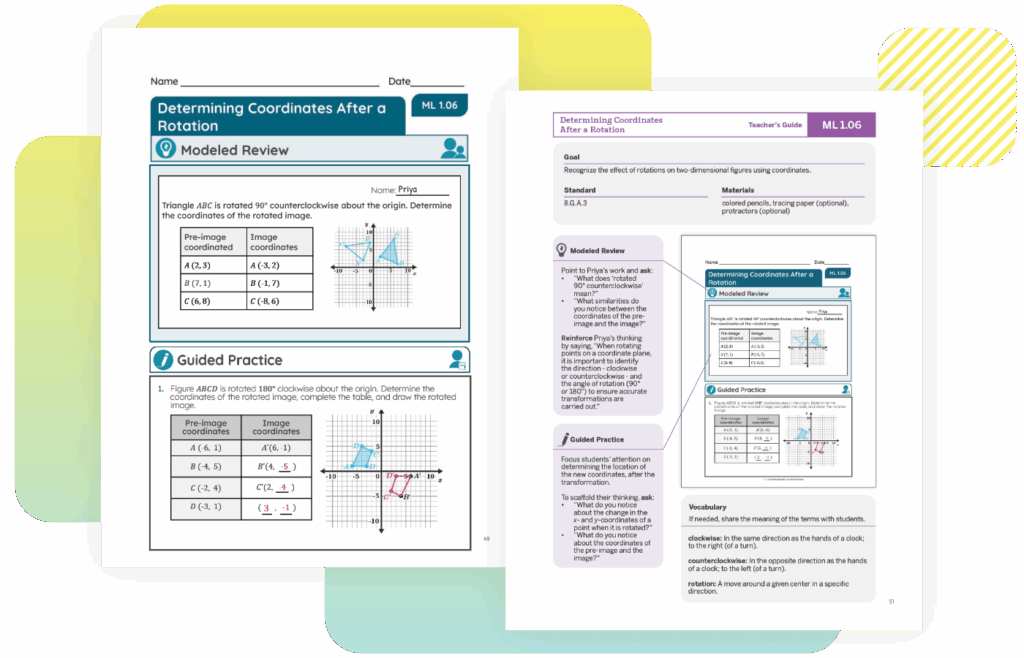

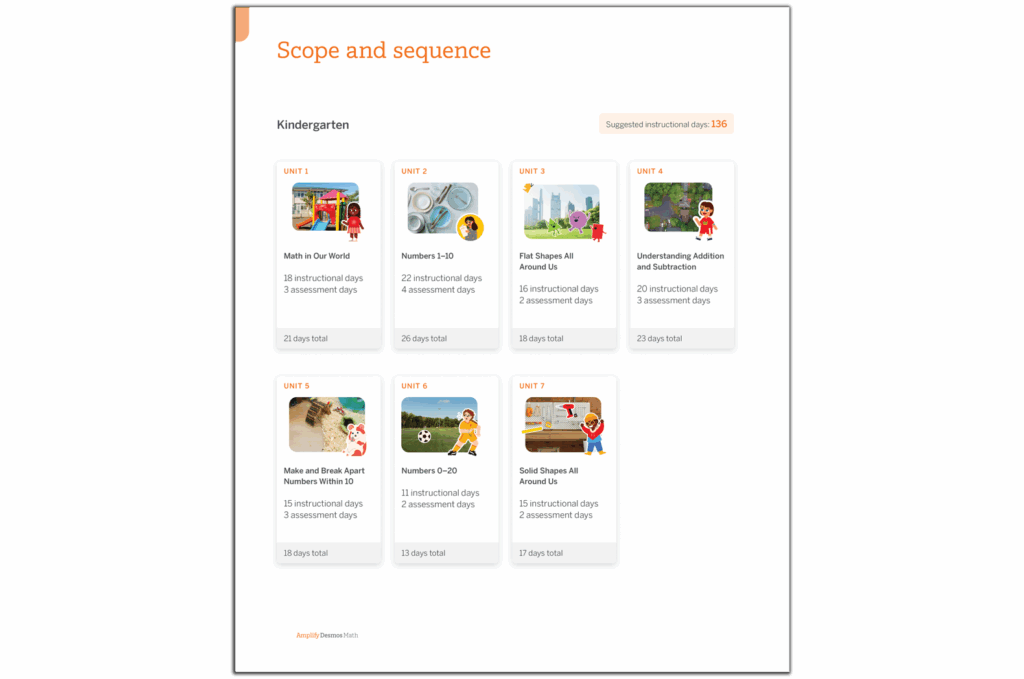

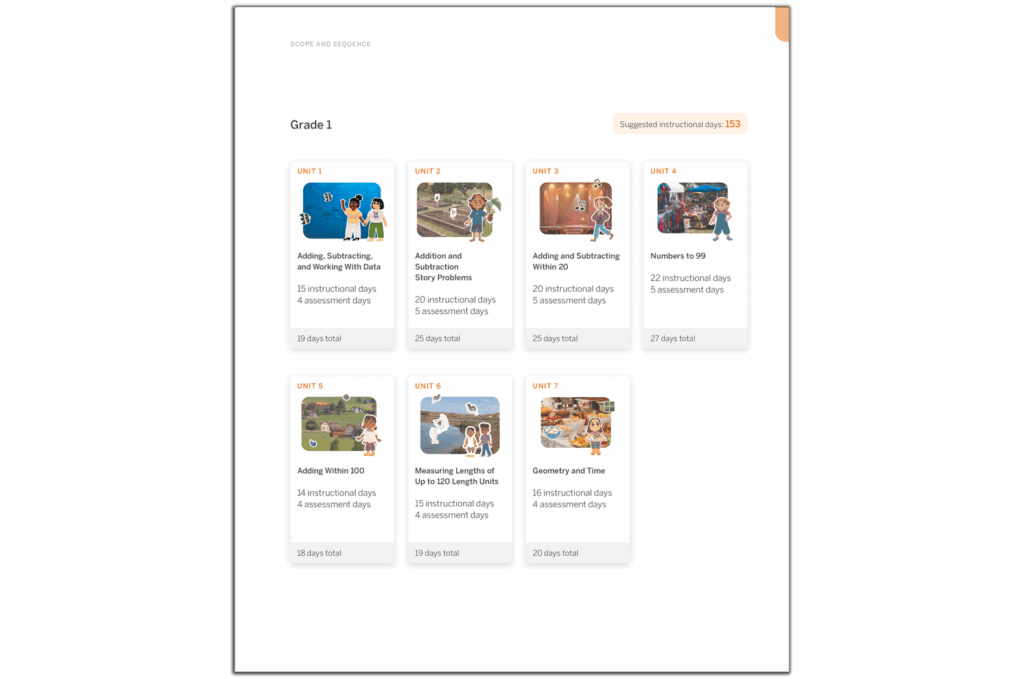

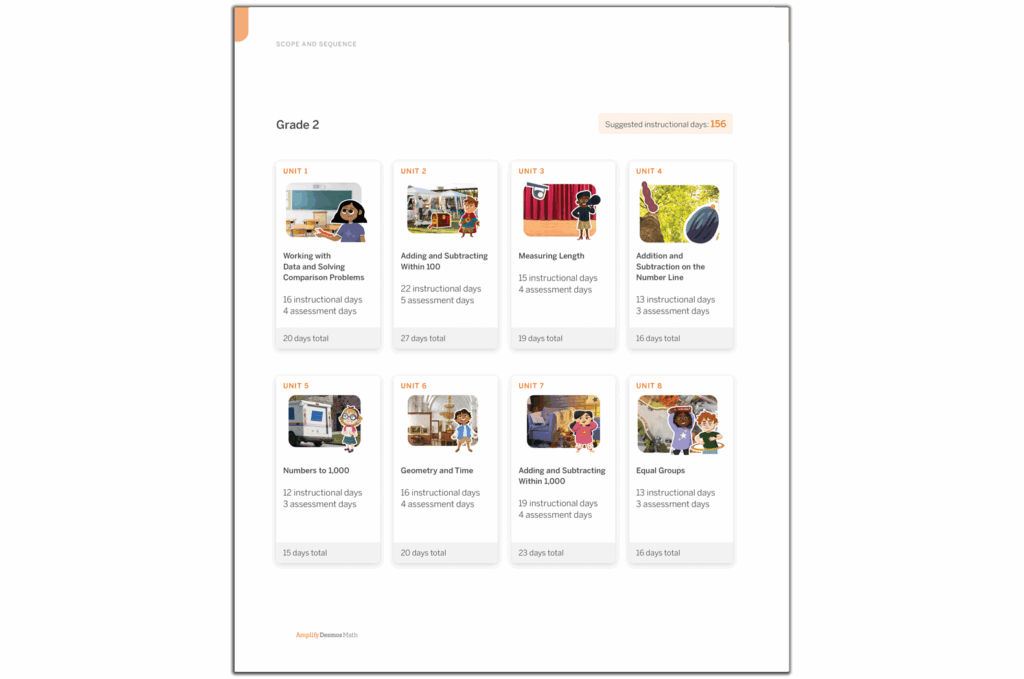

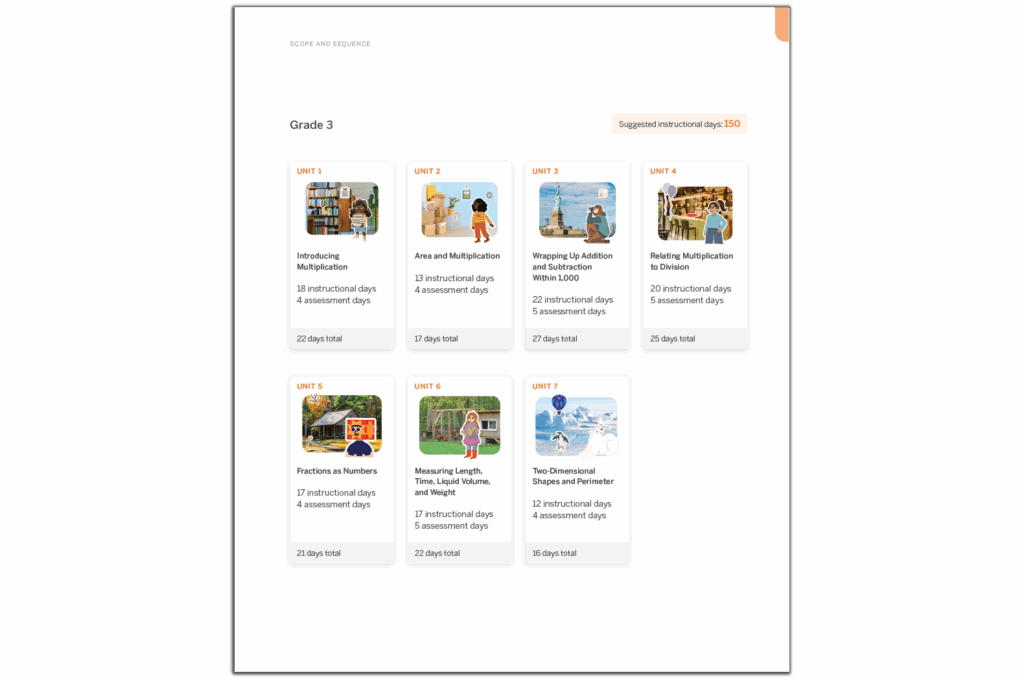

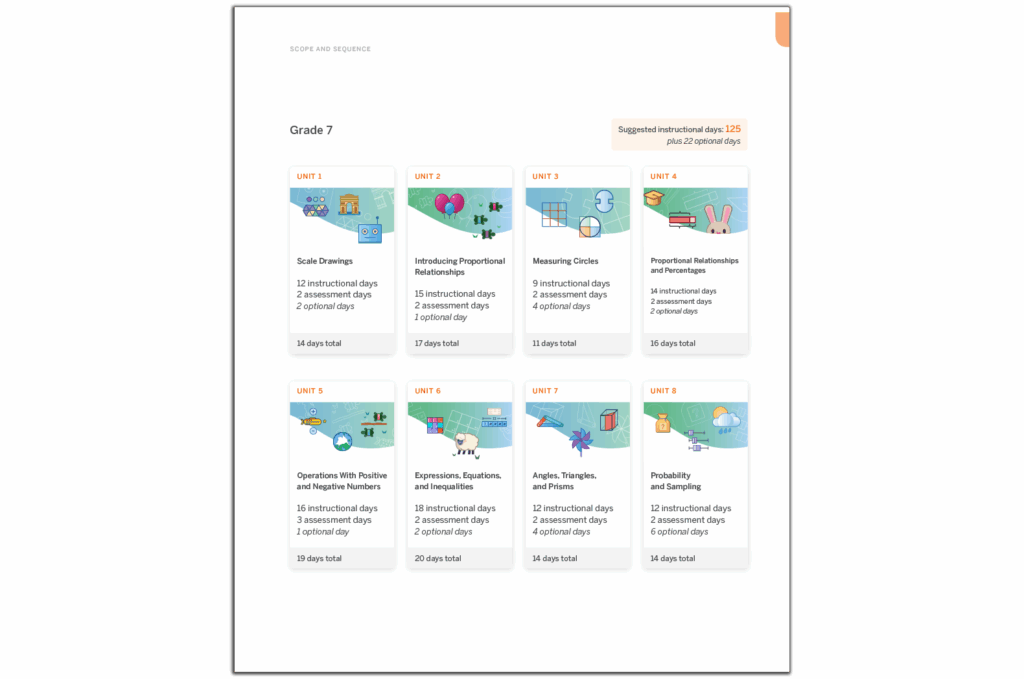

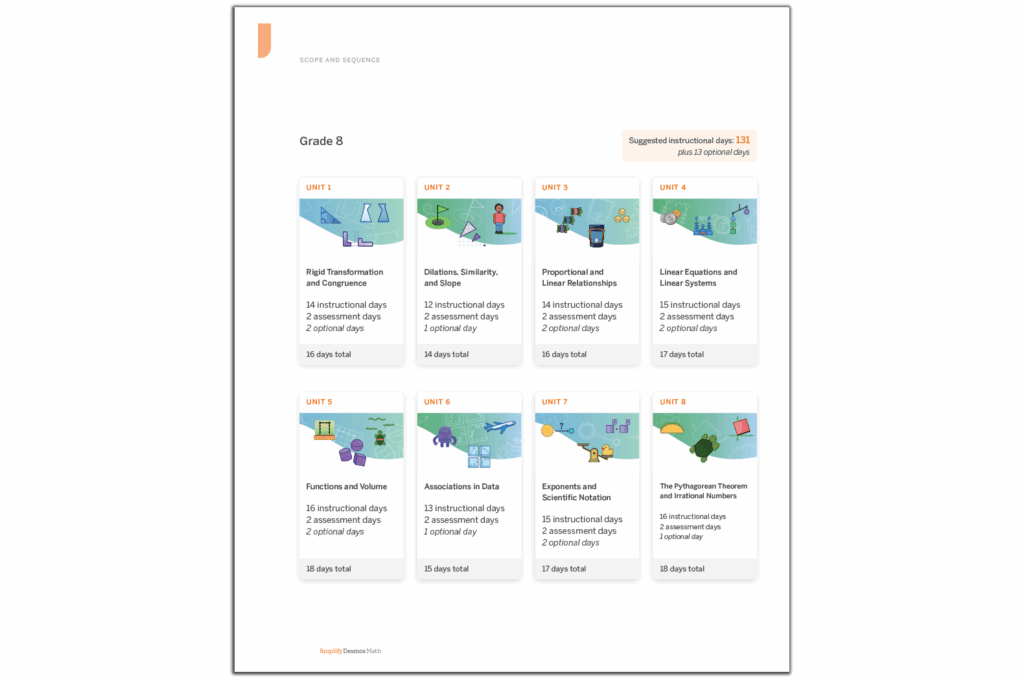

What it’s for: This program is designed to be your primary, day-to-day curriculum. It includes a complete, standards-aligned scope and sequence, print materials, digital lessons (with activities enhanced and aligned to standards), assessments, intervention resources, and personalized practice.

The bottom line: If you want a complete curriculum in which every lesson is built on polished Desmos-style activities, you want Amplify Desmos Math K–12. This core curriculum is offered exclusively by Amplify.

Quick-reference chart

| What is it? | Where to find it? | Cost | |

| Desmos Studio Tools | Powerful math tools and calculators (graphing, scientific, etc.) for graphing, calculations, and geometry visualizations. | Access via desmos.com or embedded in partner products | Free for individual use |

| Amplify Classroom | A teaching and learning platform that couples Desmos Studio tools with instruction and collaboration tools – Rich activities and lessons that develop understanding with Responsive Feedback™ – Collaboration and facilitation tools designed for the classroom – Student ideas used to build new problems and scenarios Browse free activities and lessons or build your own with Activity Builder. | Only available from Amplify at amplify.com/classroom (previously Desmos Classroom) | Free |

| Amplify Desmos Math | A comprehensive K–12 math curriculum built on the Amplify Classroom platform – Ready-to-teach print and digital curriculum built on the Amplify Classroom platform – Comprehensive coverage of all standards without the searching. – Additional support for your classroom, including assessment, differentiation, practice, professional development, and more. | Try lessons for free on Amplify Classroom Contact us for more information on purchasing for your district | With a paid subscription |

Become an Amplify Classroom Fellow!

Are you an Amplify Classroom (formerly Desmos Classroom) superfan or a math educator who loves using technology to make learning come alive? If so, consider applying to join the next Amplify Classroom Fellows cohort, a passionate community of math educators who inspire one another and help shape the future of Amplify’s products!

Applications are open through Jan. 30, 2026.

If you have any questions, reach out to amplifyclassroomfellows@amplify.com.

What is the Amplify Classroom Fellowship?

The Amplify Classroom Fellowship is a professional learning community of K–12 math educators who:

- Use Amplify Classroom to empower students’ mathematical thinking.

- Share insights, strategies, and inspiration with peers.

- Care deeply about making math learning accessible and engaging for all students.

As an Amplify Classroom Fellow, you’ll receive:

- Invitations to unique professional development experiences, both online and in person.

- Opportunities to connect with the Amplify Classroom Fellows community of peers and Amplify teams.

- Early access to learn about new features before other educators.

We ask participants to:

- Share experiences through presentations, publications, and educator events during the school year.

- Connect and collaborate with like-minded educators and Amplify teams.

- Attend an in-person New Fellows Orientation event in mid-July 2026.

Interested in becoming an Amplify Classroom Fellow?

Applications are open through Jan. 30, 2026.

If you have any questions, reach out to amplifyclassroomfellows@amplify.com.

Amplify Desmos Math for NYC

Welcome! This site contains supporting resources for the New York City Department of Education Amplify Desmos Math adoption for grade 6–A1.

What’s new?

- Prepare for 2025–26! Get everything you need to teach Amplify Demos Math with this checklist.

- Use this guide to learn about the materials included through Core Curriculum purchases.

- Need help? Check here for who can help! Our dedicated phone number, just for NYC, has team members ready to help! 1-888-960-0380

About the program

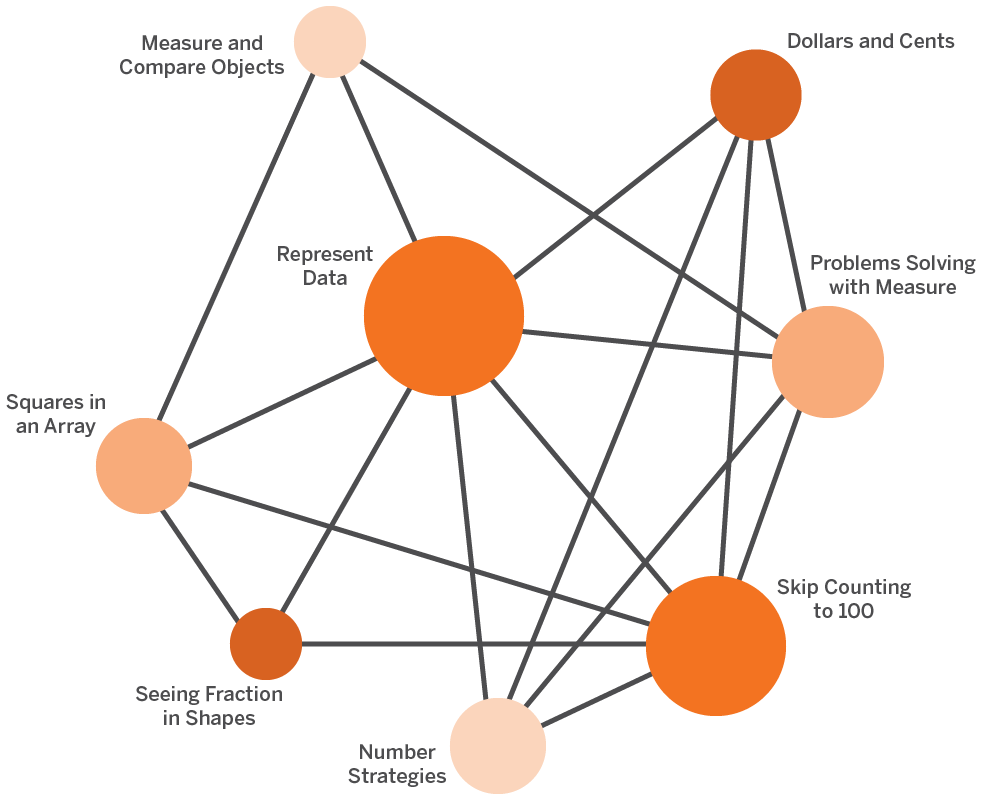

Amplify Desmos Math New York is based on Illustrative Mathematics® IM K–12™ and expands on Desmos Math 6–8 (which received all-green ratings from EdReports) with beautiful print resources, and robust practice, differentiation supports, assessment and reporting. Read the review on EdReports.

Amplify Desmos Math provides:

- Engaging, discourse-rich math lessons that are easier to teach.

- Flexible, collaborative problem-solving experiences both online and off.

- Real-time insights that make student thinking more transparent.

Program highlights to know about

- Getting started with Amplify Desmos Math Video (coming soon)

- Curriculum overview and background

- Examples of implementation

- Implementation considerations

- Caregiver Resources

- Multilingual Learner Supports

- Packing List

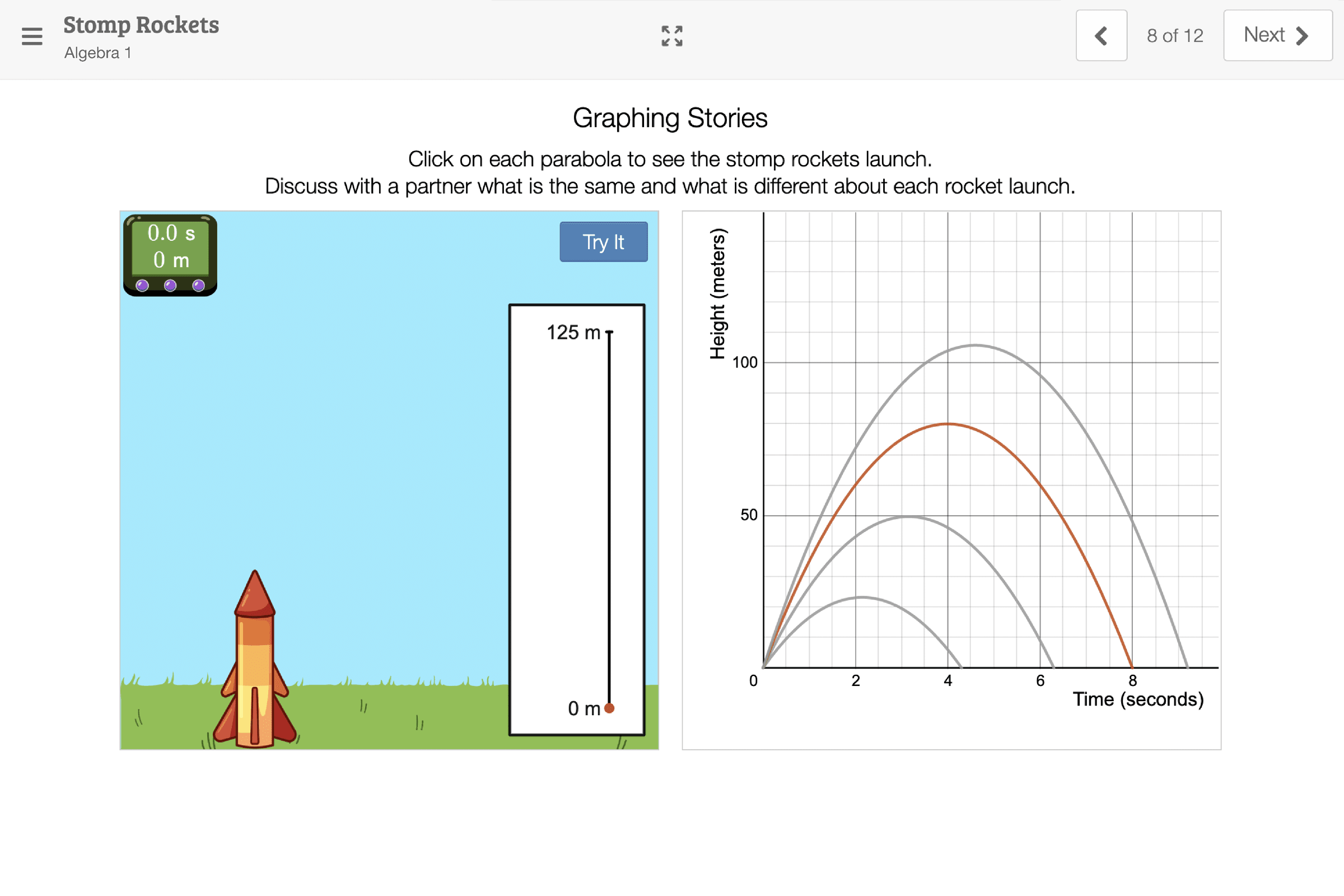

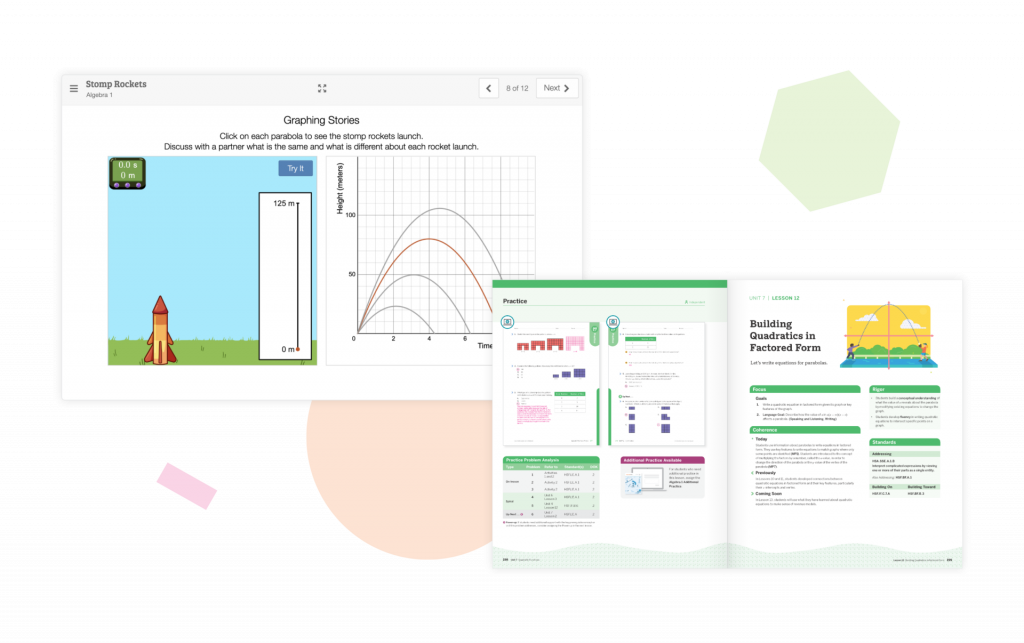

Desmos Classroom digital lessons

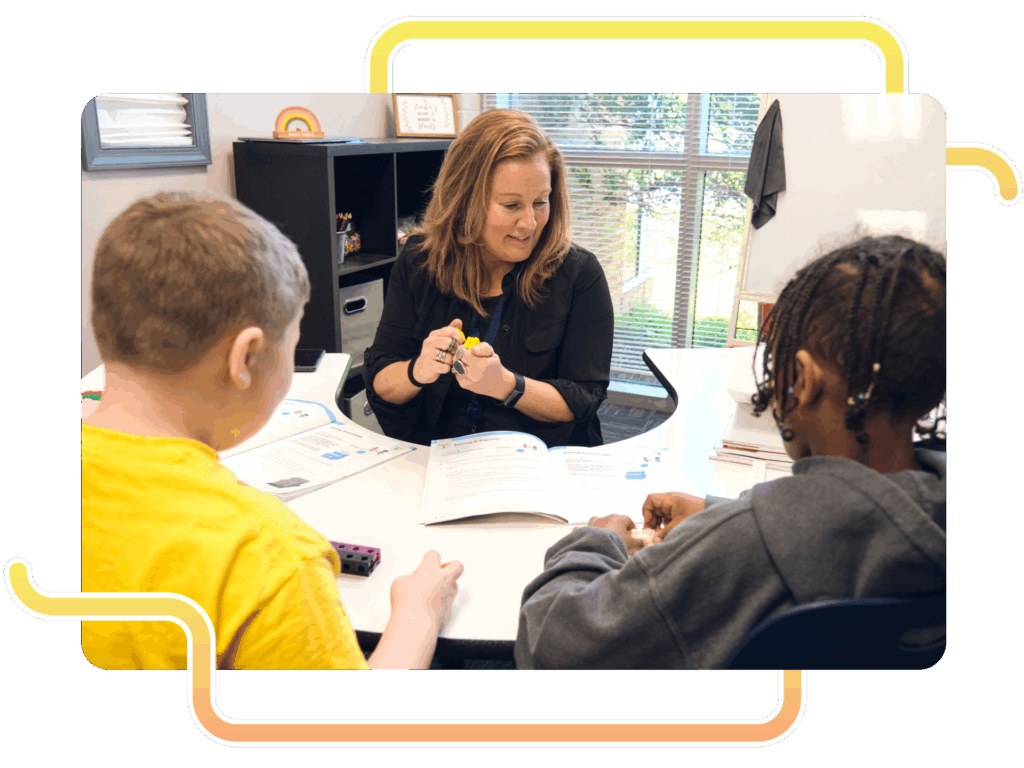

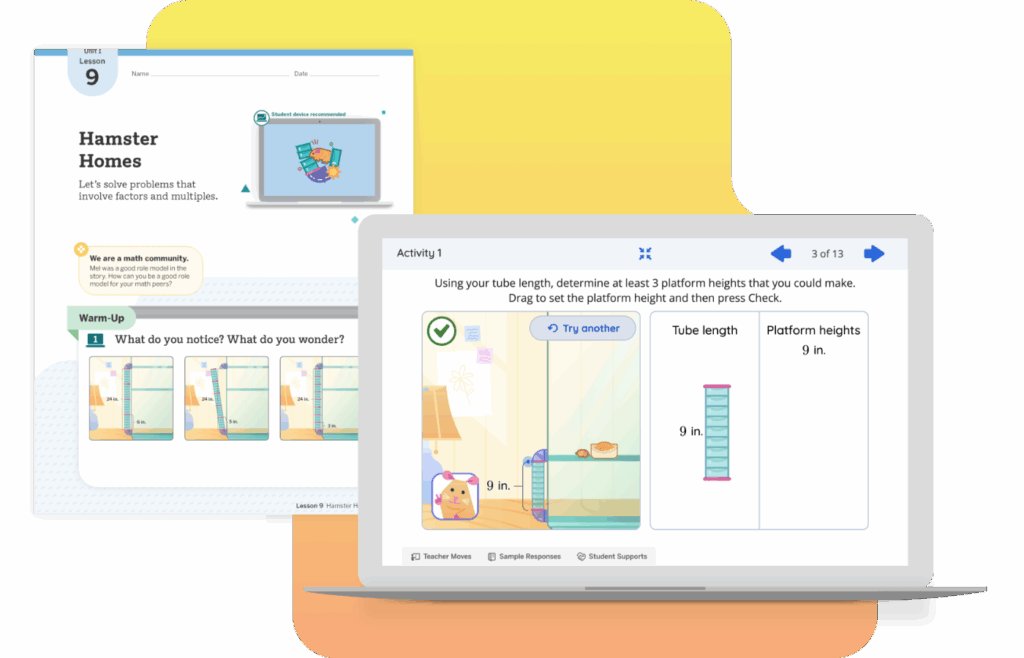

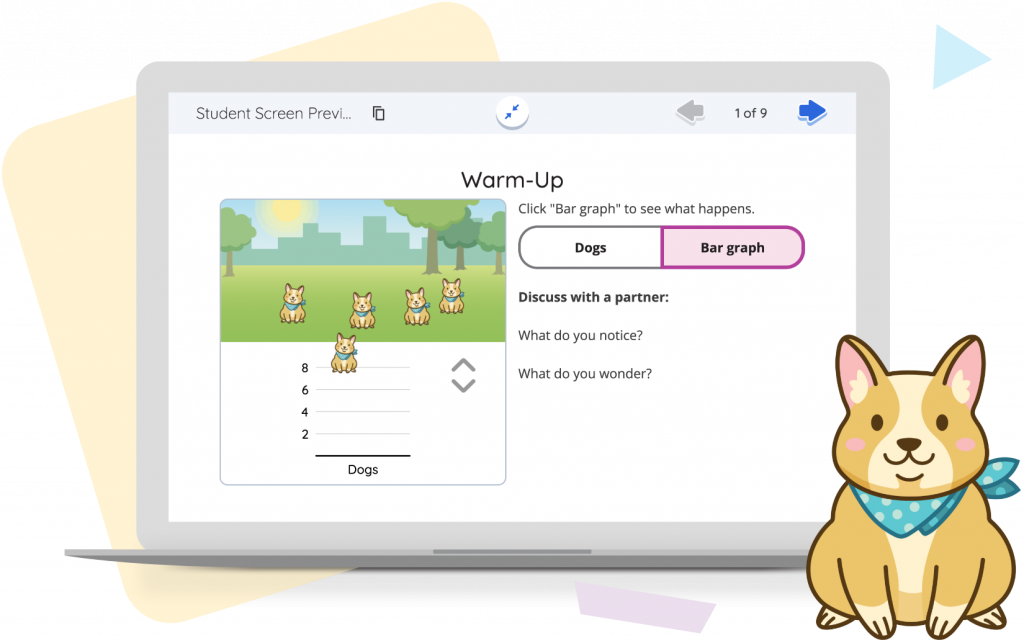

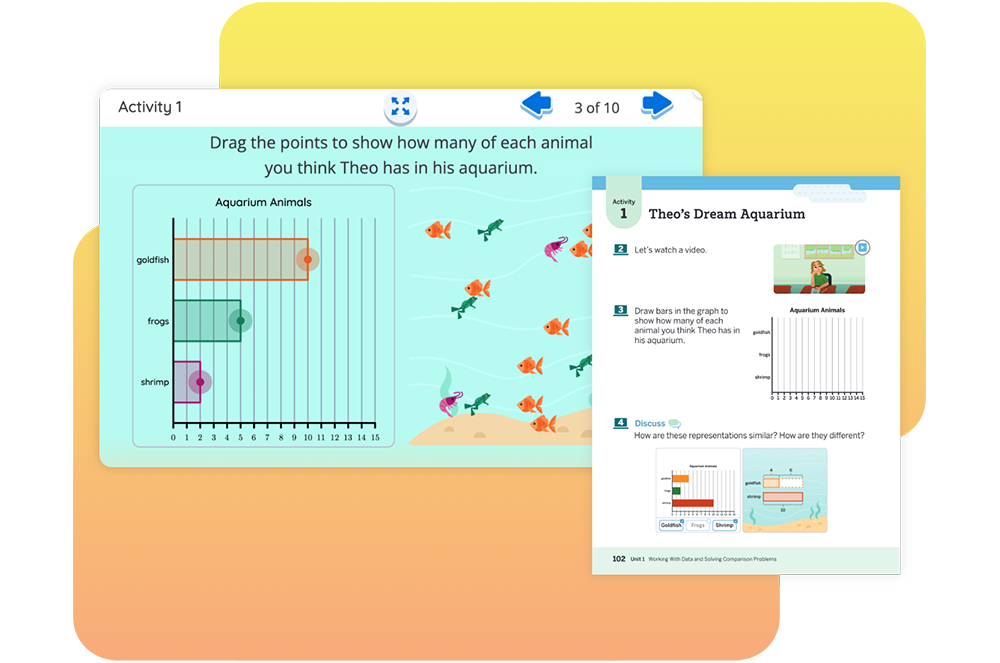

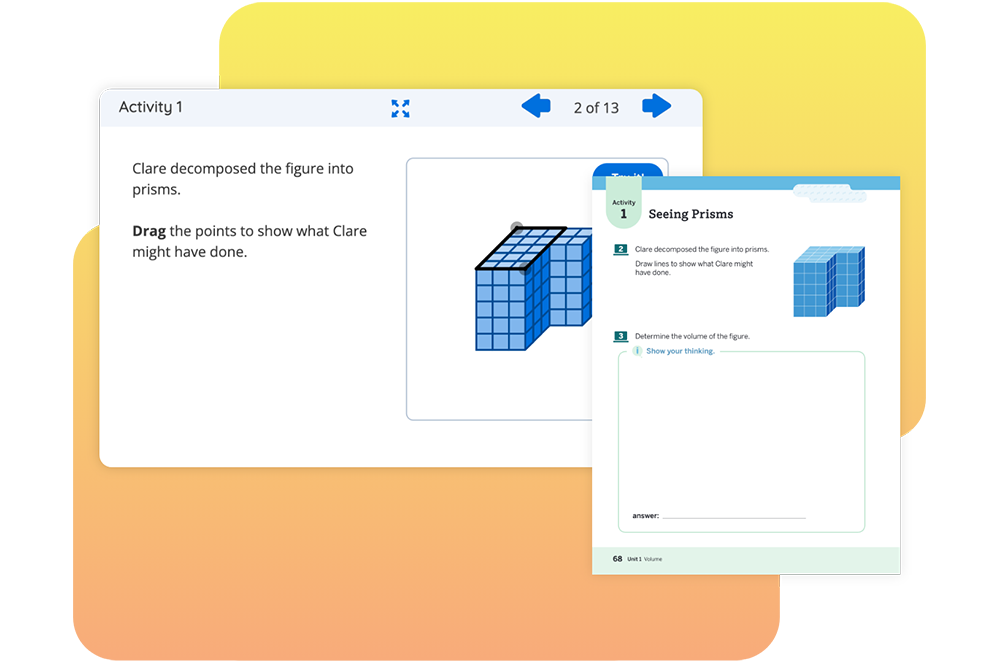

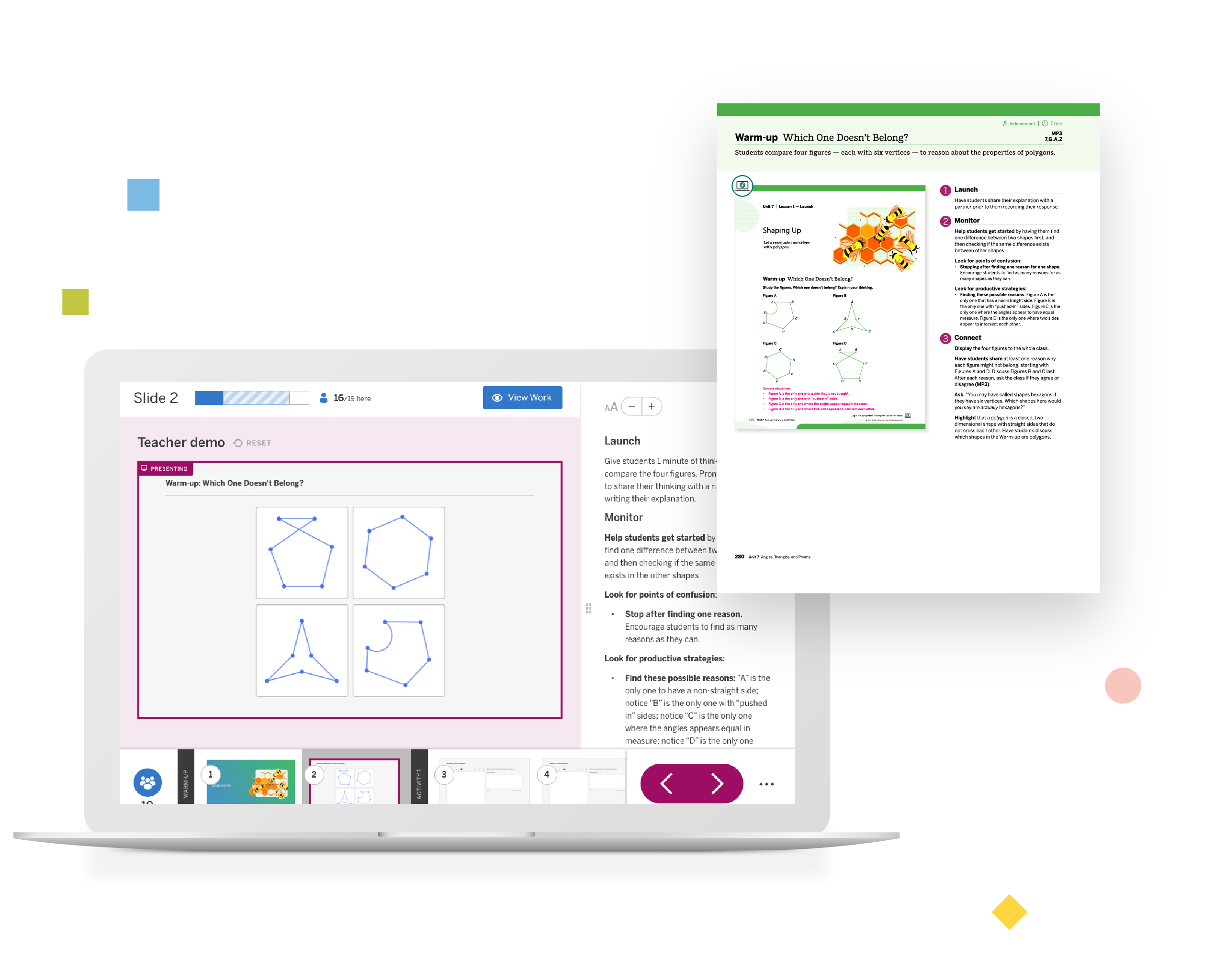

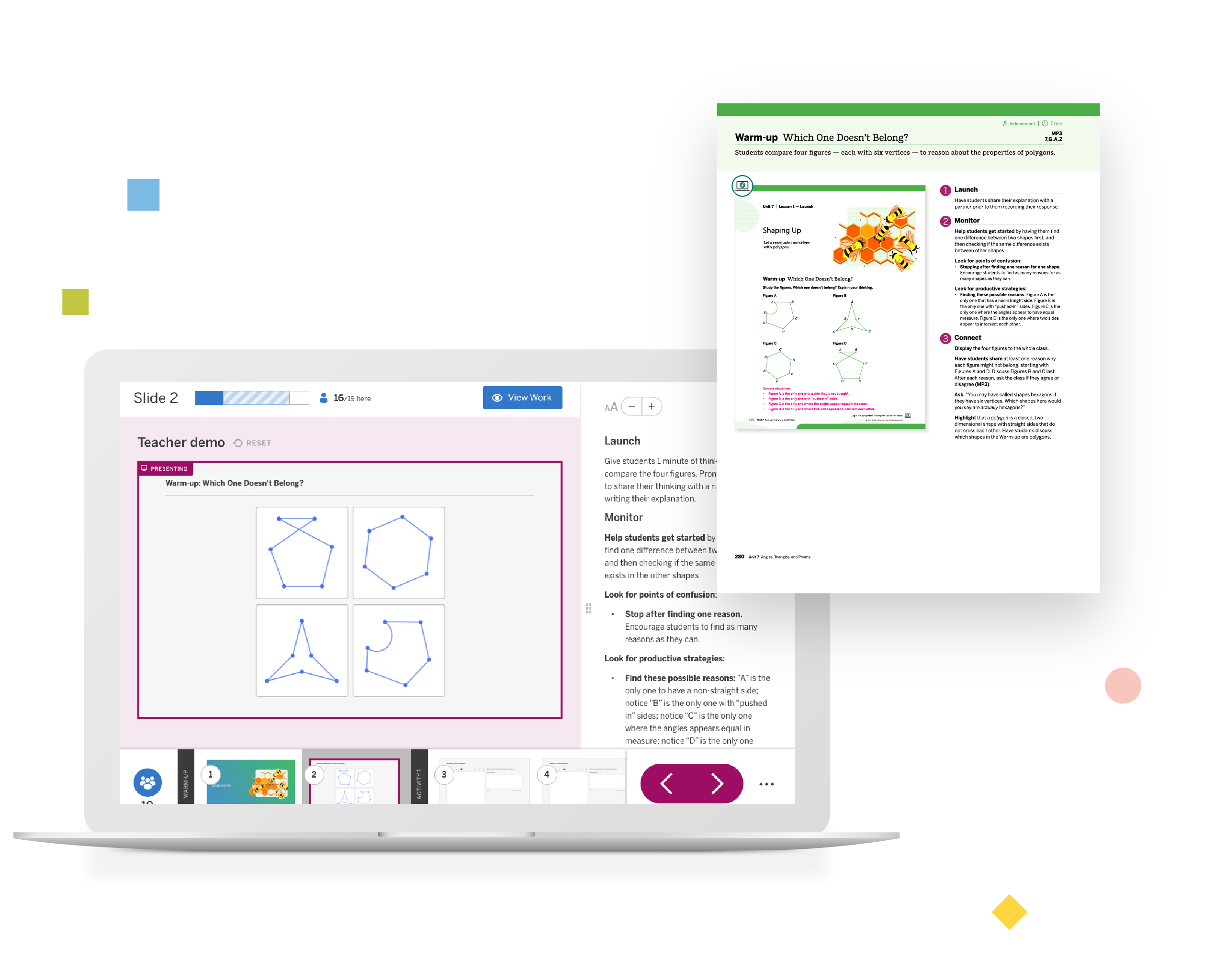

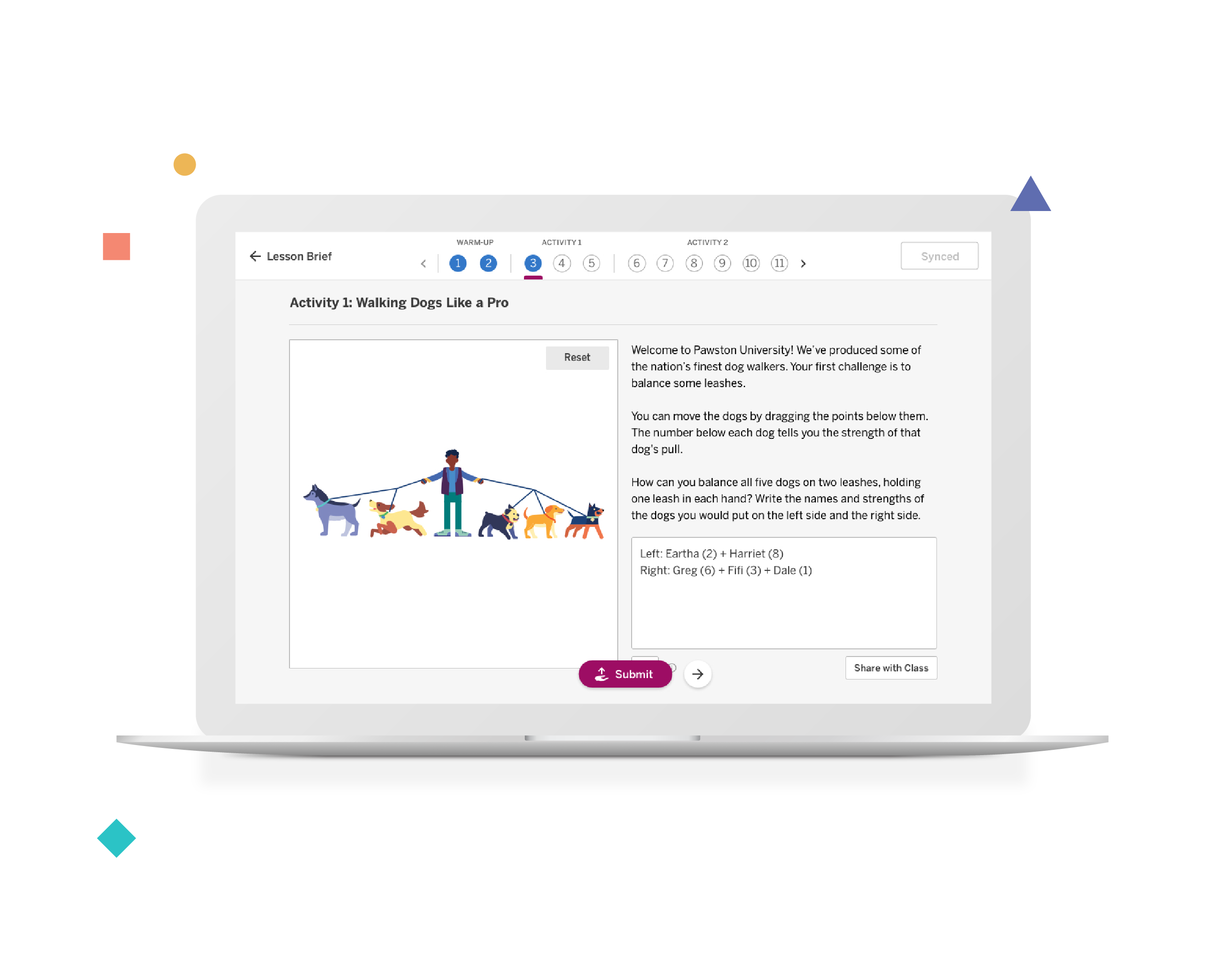

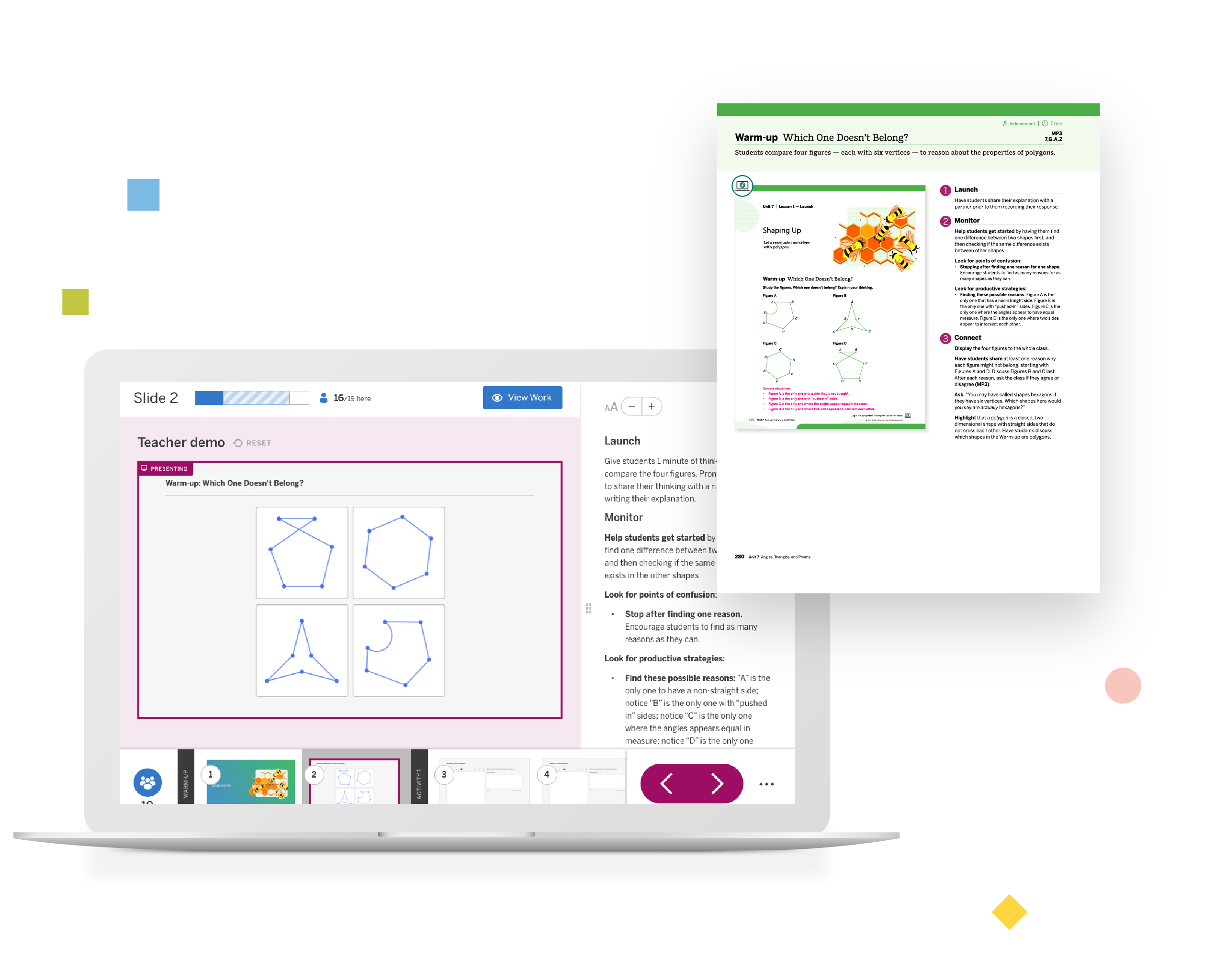

Digital lessons should be powerful in their ability to surface student thinking and spark interesting and productive discussions. We’ve joined forces with Desmos Classroom to bring this vision to life with a complete library of interactive, collaborative lessons.

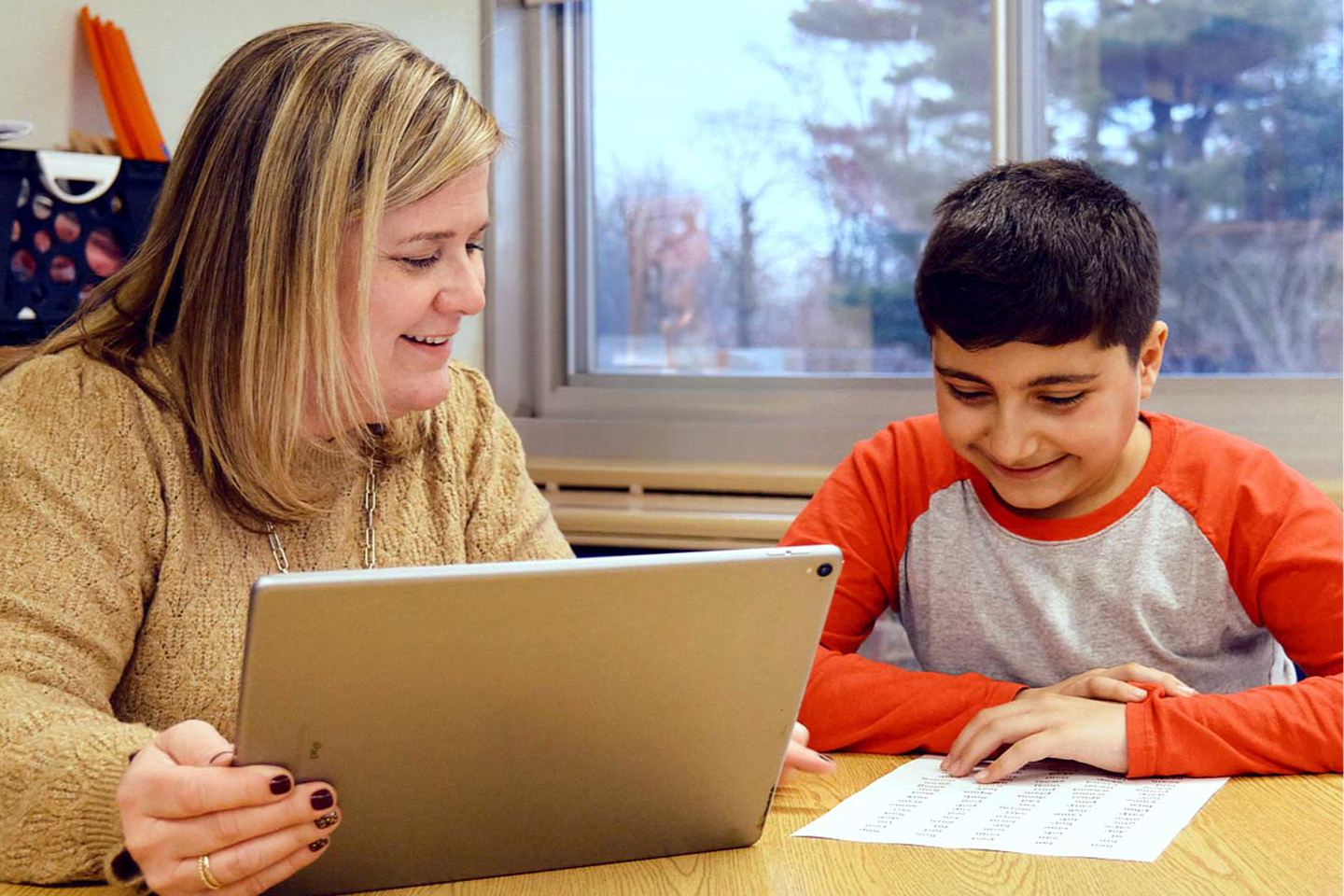

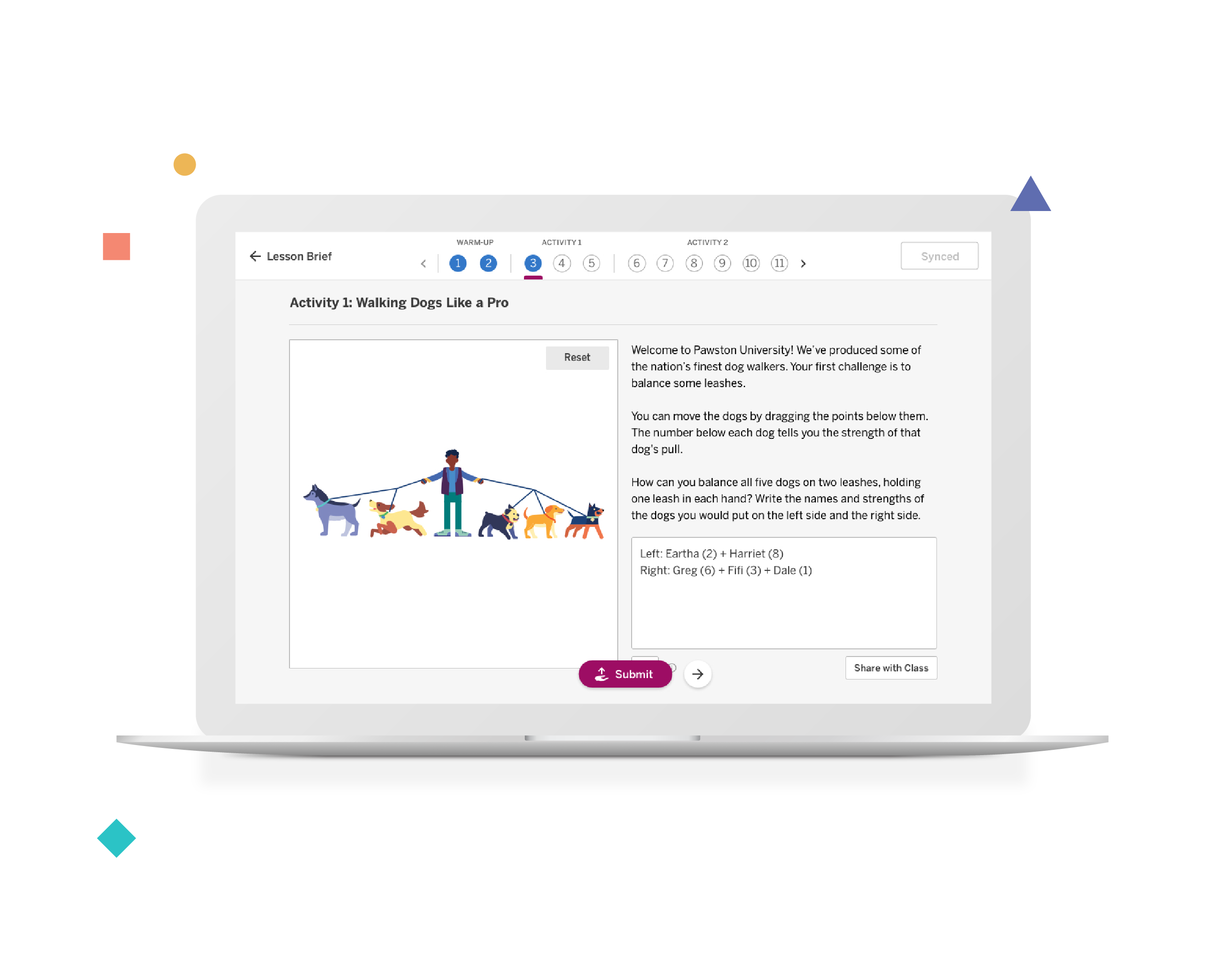

Engaging student experience

Relevant content and interactive math tools create an intuitive and engaging student experience. Plus, working together in real time allows students to see that communicating their ideas and learning from each other are important parts of math class.

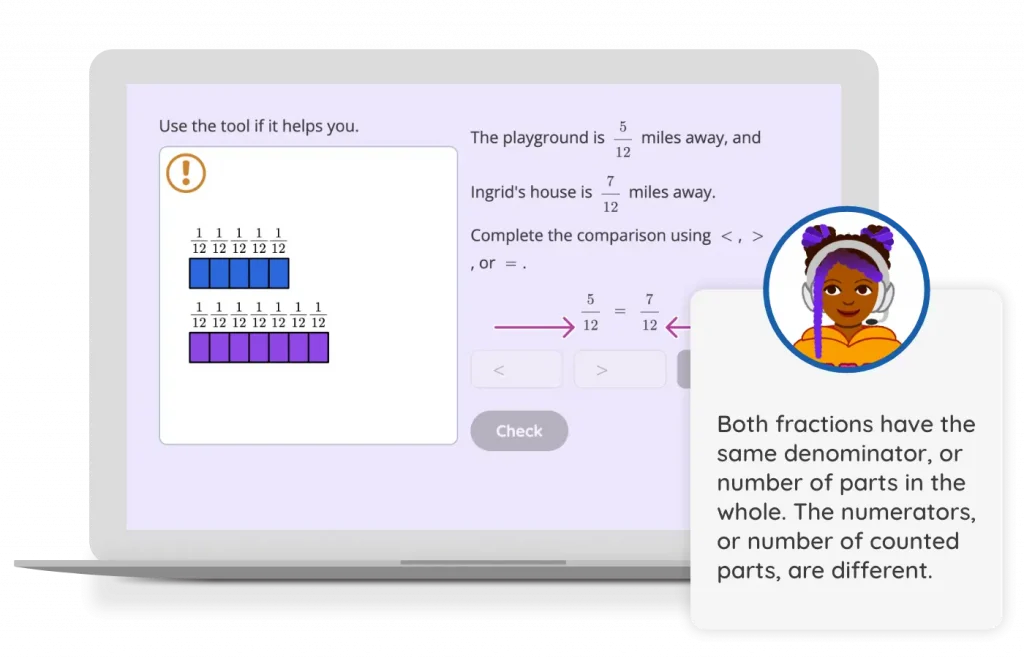

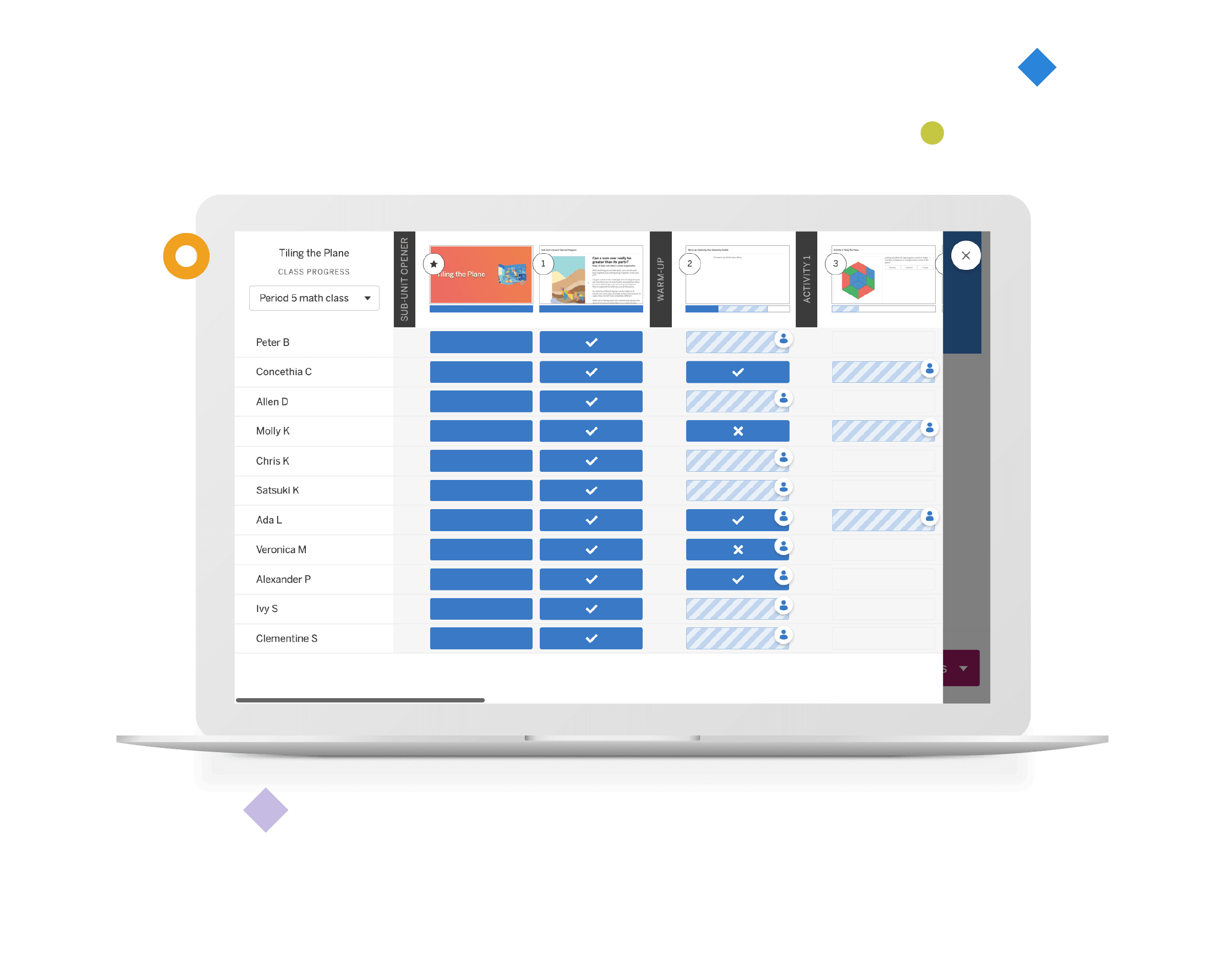

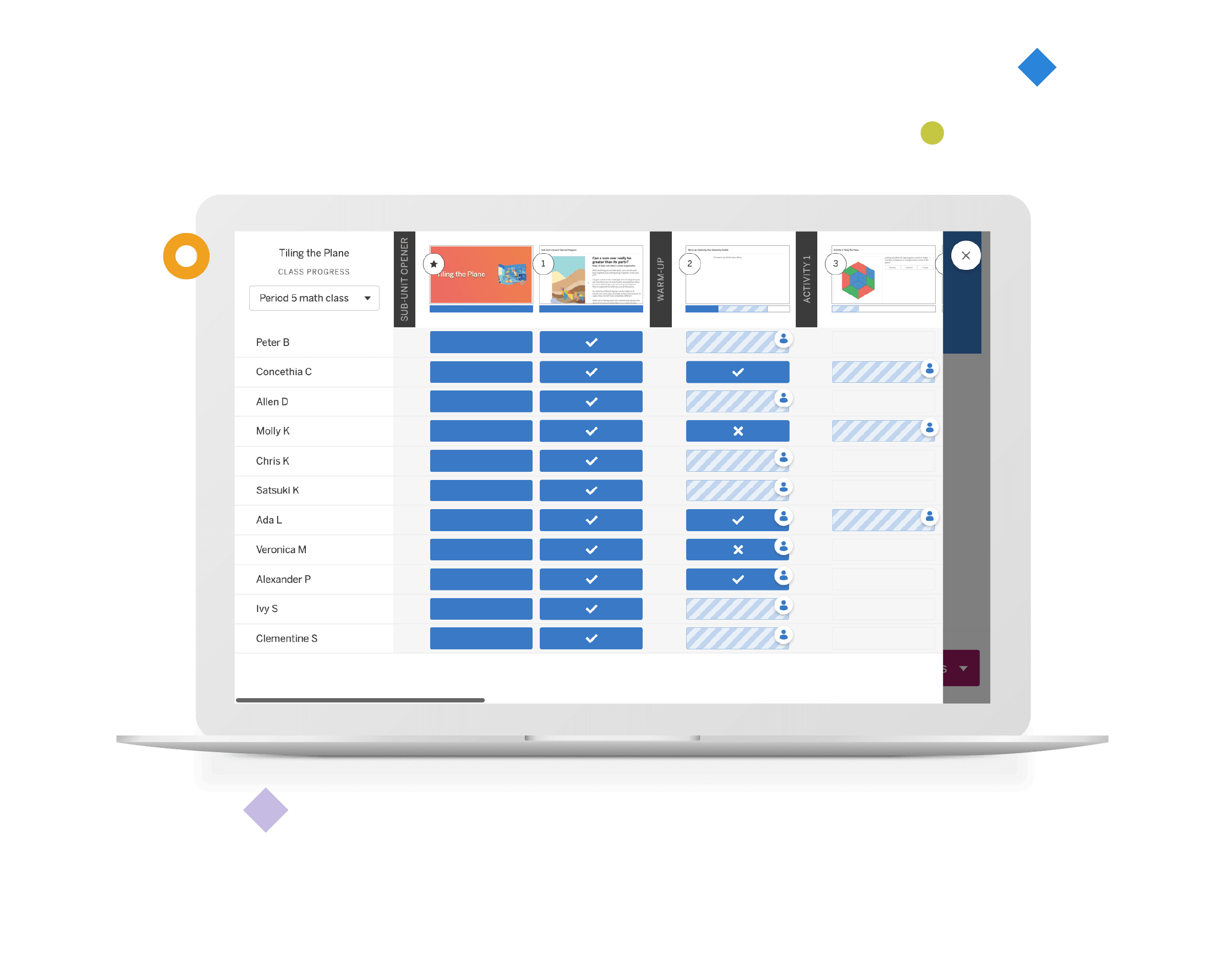

Visibility into student thinking

Imagine having more visibility into your students’ mathematical thinking. Now imagine that students have access to this same information. With our collaborative lesson interface and teacher dashboard, students have awareness their own thinking and that of their peers—exposing them to a wider variety of approaches to solving the same problem.

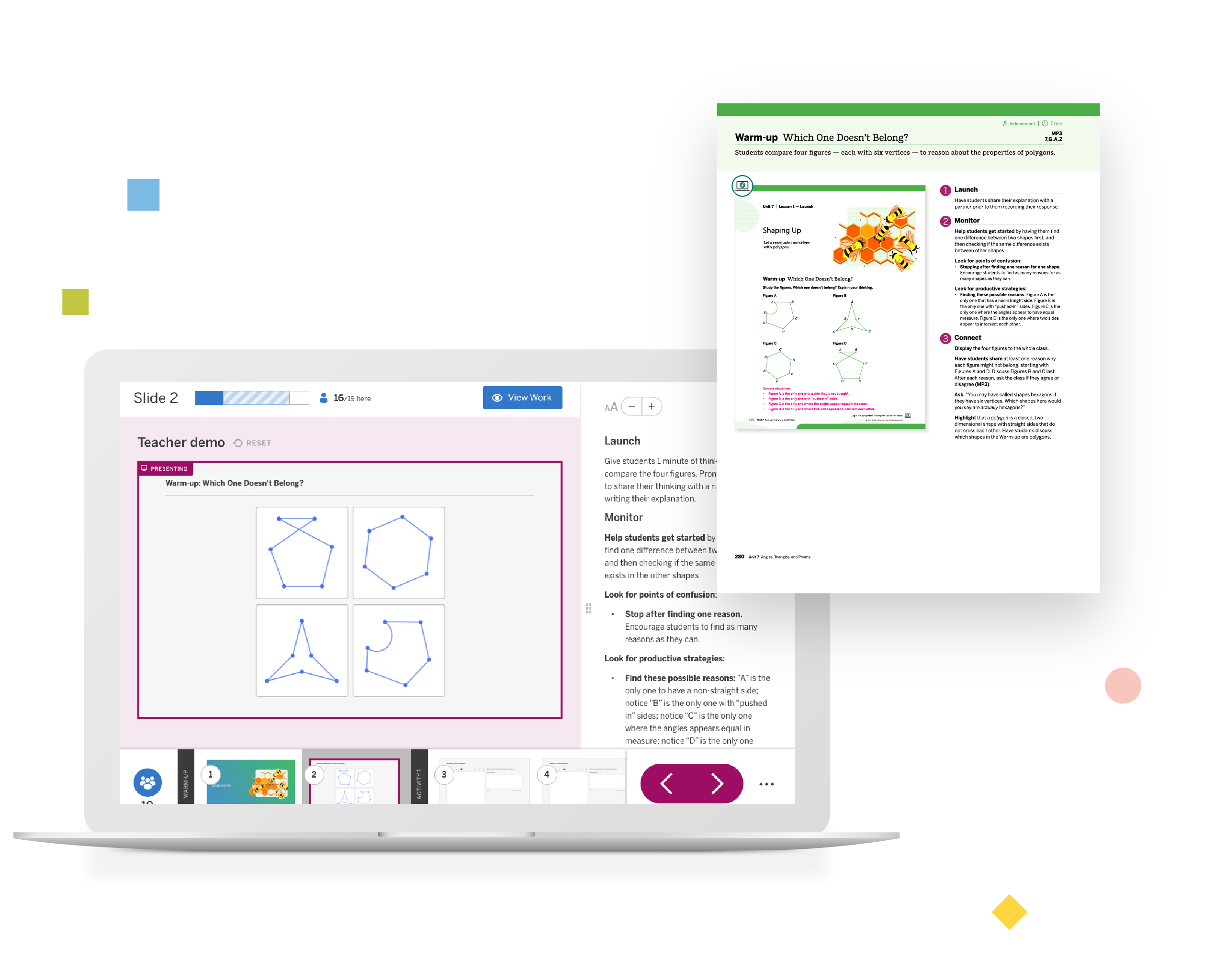

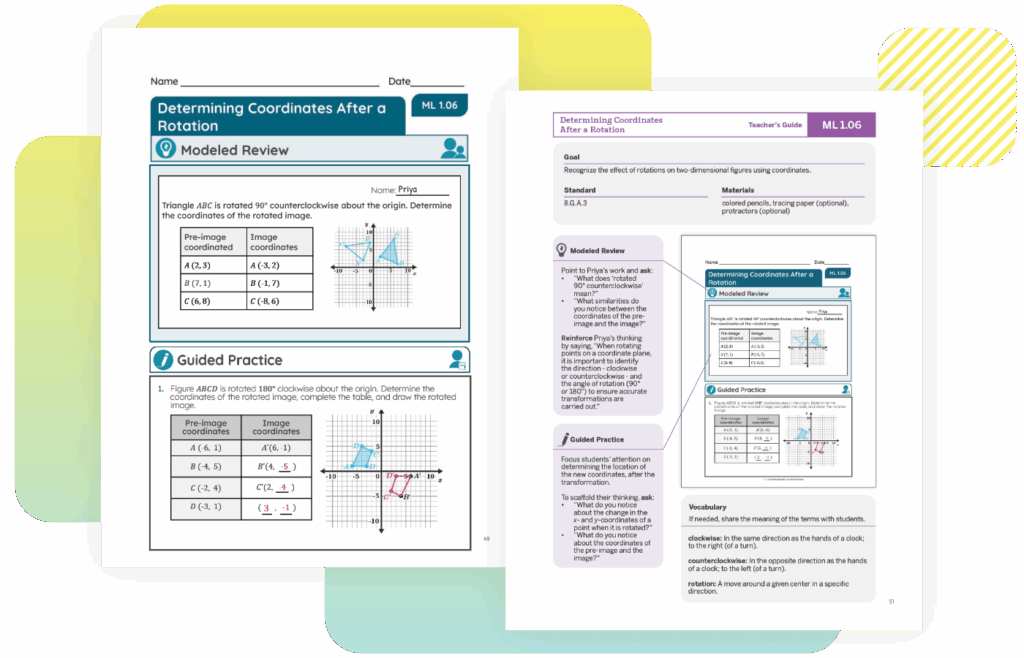

Ready-to-teach lessons

Each grade level includes 150 ready-to-teach lessons, complete with slides, step-by-step teaching notes, suggested student and teacher responses, tips for incorporating instructional routines, support for developing mathematical language, and links to useful resources. Teachers can manage what slides students see, controlling the pace of the lesson to suit the needs of the class.

Planning for instruction

Amplify Desmos Math is customized specifically to meet the New York State Next Generation Math Learning Standards. Within each document below, you’ll find direct links to lessons and activities where each individual standard is addressed.

The program is also aligned with the expectations outlined in the New York City Department of Education Definition of Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education and the New York State Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework. Download the CR-SE alignment.

Amplify Desmos Math Scope and Sequence

Amplify Desmos Math Accelerated Scope and Sequence

Ready to plan for the 2025-26 school year? These pacing guides are designed to provide structure, not rigid mandates and resources for NYC.

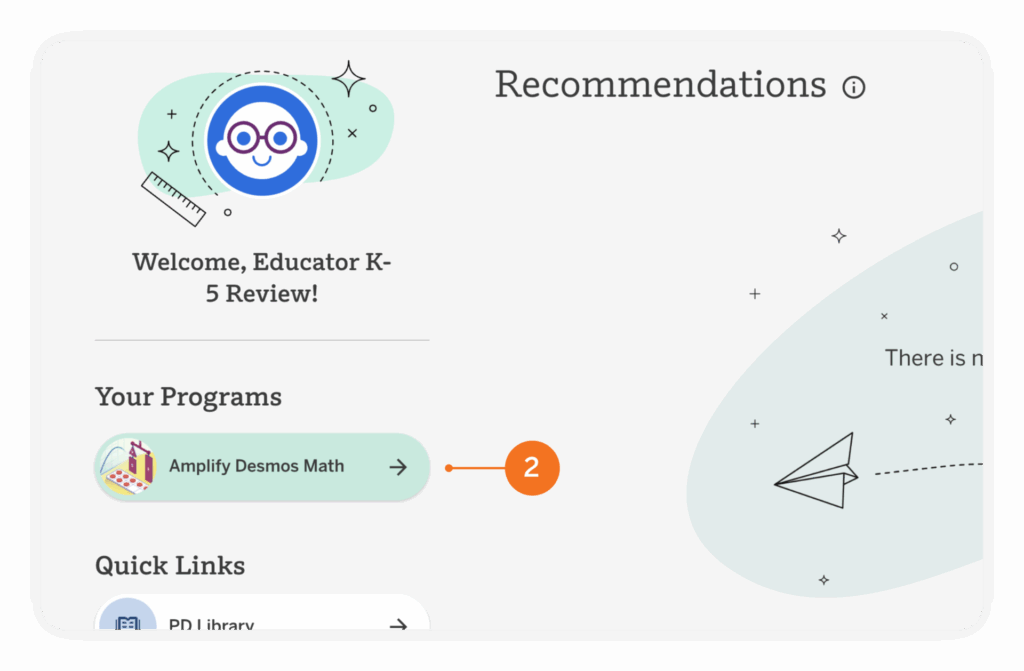

Experience Amplify Desmos Math New York

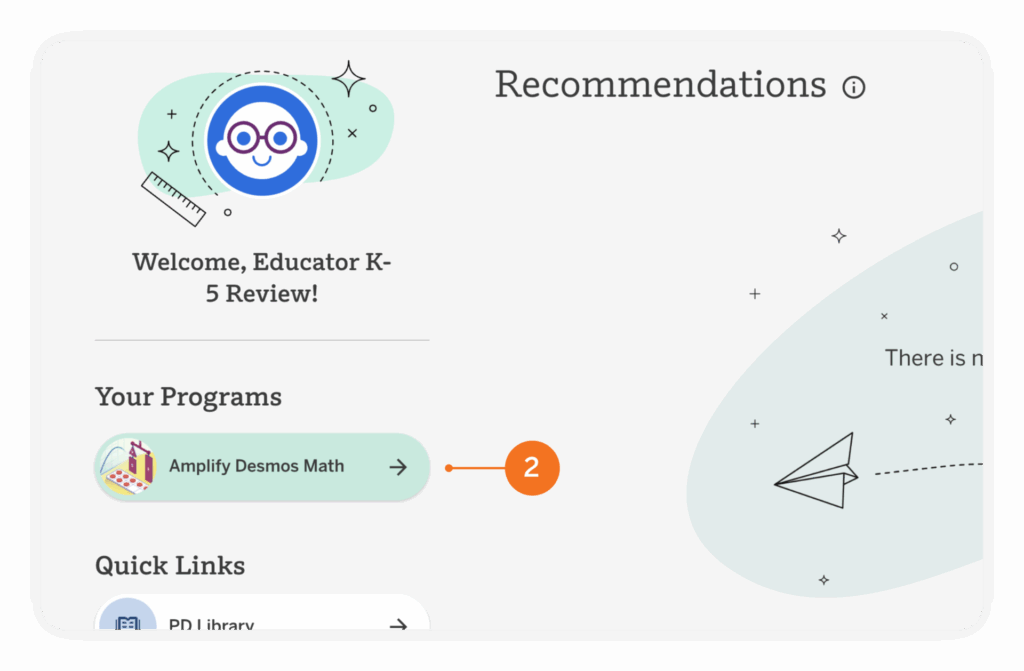

Explore our digital program to review content from all grades, 6–A1. Watch our quick walkthrough video for helpful navigation tips.

Try out Amplify Desmos Math by following these steps.

Printable login instructions:

- Teachers: Log in with Amplify steps 1–3 and steps 4–6 or TeachHub (district-preferred login method)

- Administrators: Log in with Amplify or TeachHub (district-preferred login method)

- Students: Log in with Amplify steps 1–3 and steps 4–6 or TeachHub (district-preferred login method)

Additional support:

- How to reset student(s) password

- How to log my class out of a shared device

- Clever class logout instructions

- Single session codes

Print Materials List:

Lesson Sampler

Amplify Desmos Math delivers the instructional power of student-centered learning packaged in a lesson format that’s teacher-friendly and manageable.

With easy-to-follow instructional support, implementing a problem-based program becomes more effective and enjoyable for both you and your students. Paired with the Desmos Classroom digital experience, math class is suddenly fun and dynamic, with plenty of opportunities for students to talk through their reasoning, work with their peers, and gain new understanding.

Additional features

Universal design

Every student is brilliant, and every student has brilliant mathematical ideas worth sharing and cultivating. Incorporating principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into lessons brings students’ brilliance to the forefront. UDL is a research-based framework designed to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

Diversity and representation

Helping students develop strong, healthy, and flexible math identities is a cornerstone of our program. Throughout the curriculum, students are taught that they themselves are mathematicians, that today’s math has been shaped by a diverse range of mathematicians who deserve to be celebrated, and that learning is never finished.

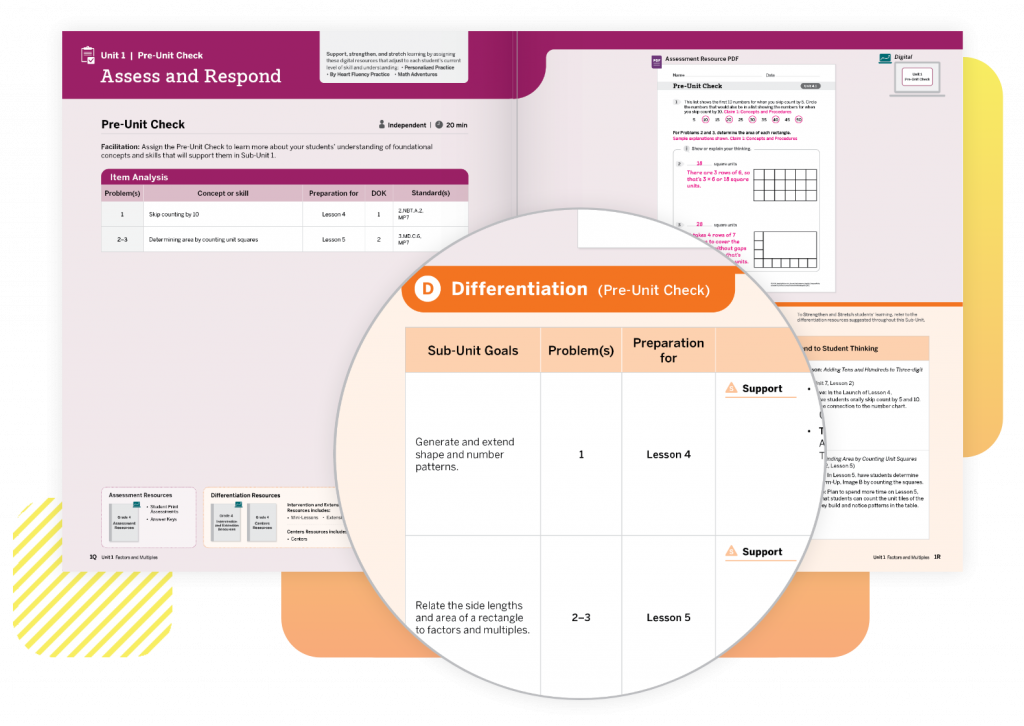

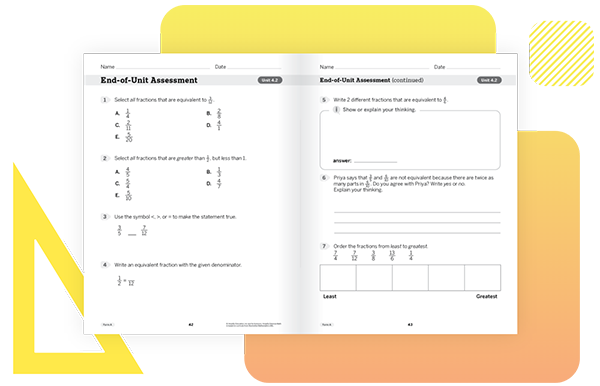

Assessments

Less exciting, but essential for learning: assessments. Amplify Desmos Math features a robust variety of formative and summative assessments, including readiness checks, exit tickets, quizzes, end-of-unit tests, and benchmarks aligned with New York State Next Generation Mathematics Learning Standards.

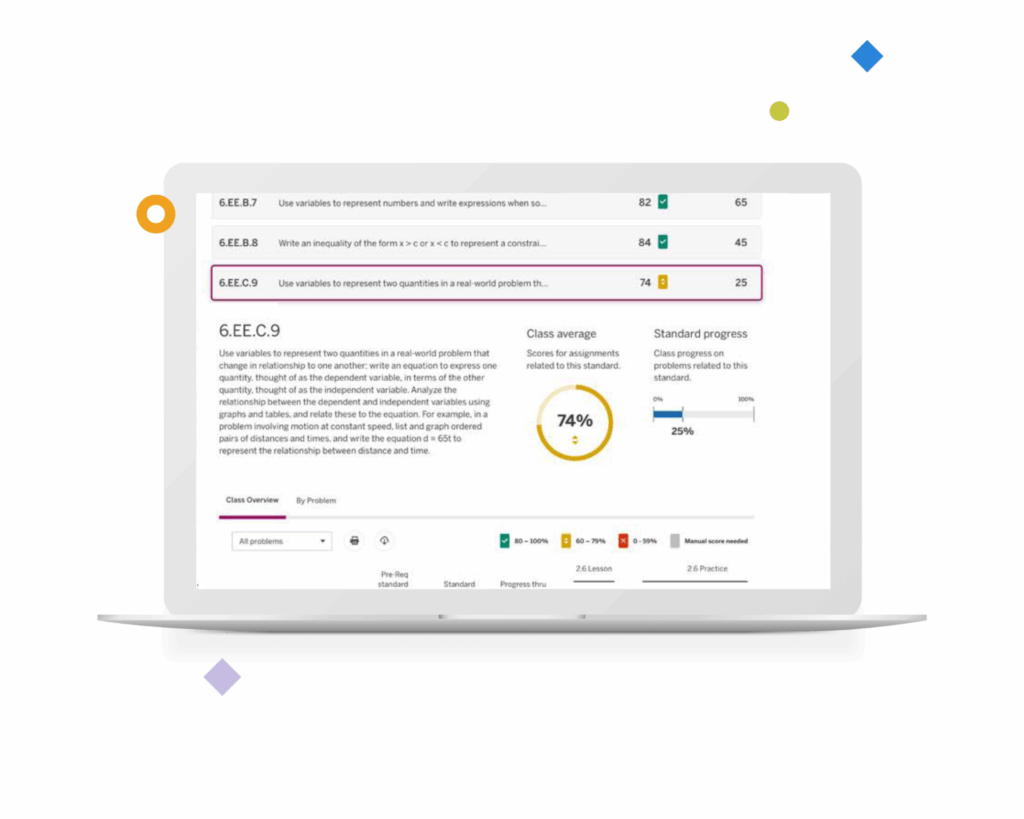

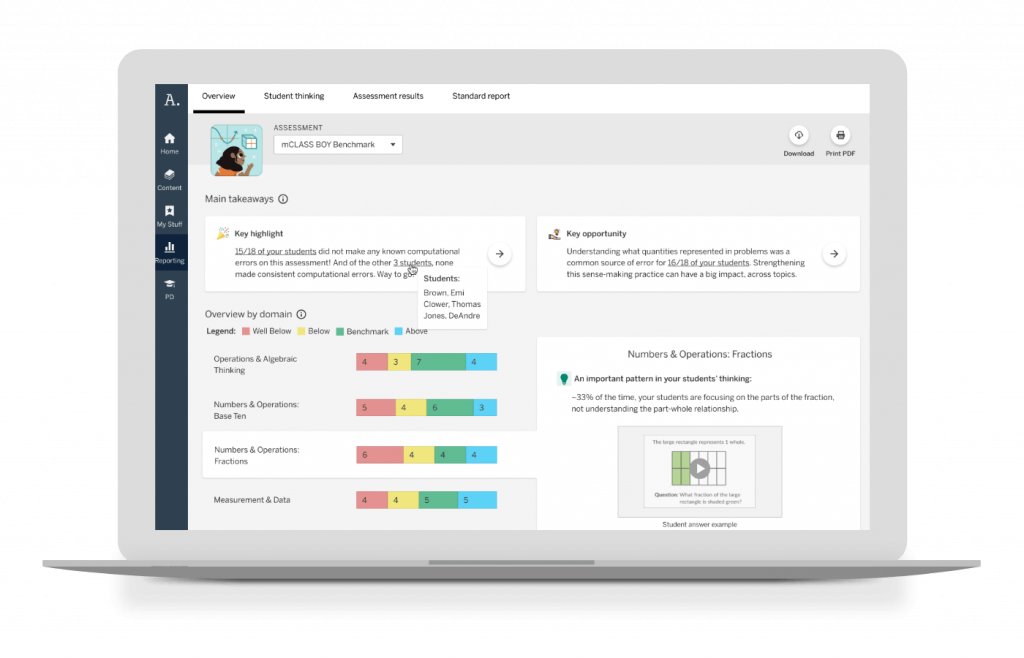

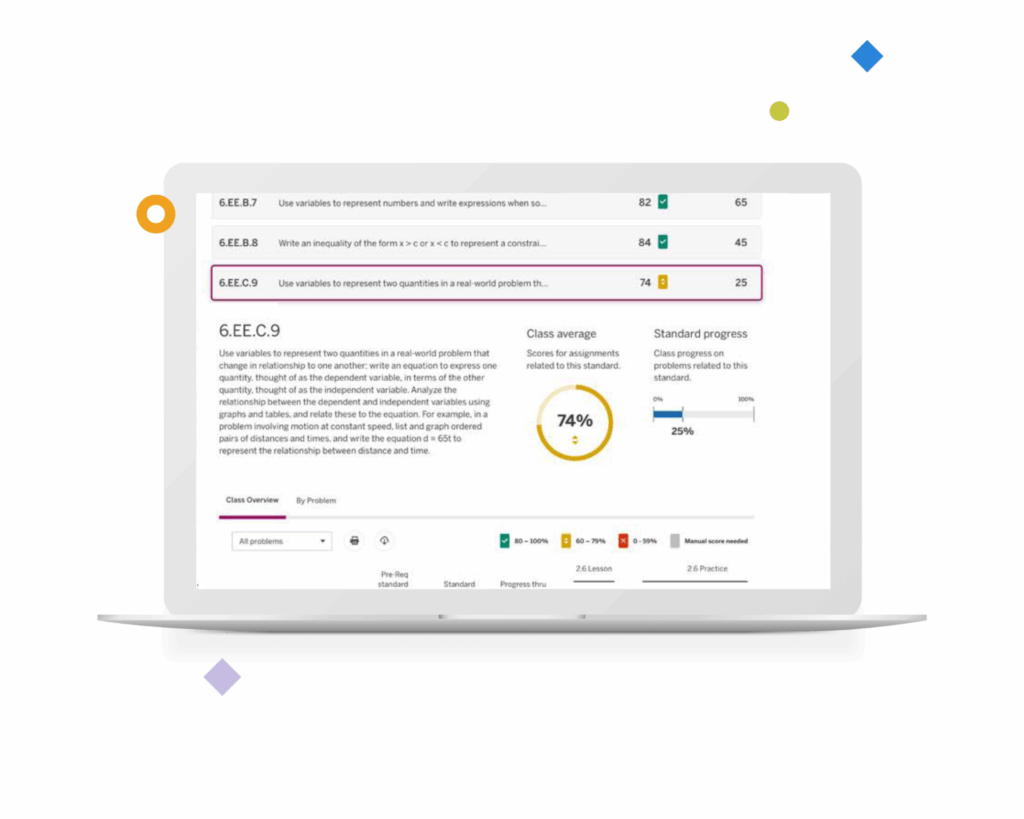

Reporting

Not only do our reports reveal progress toward standard mastery, but they also include details on how students performed against the standard in the past and how many encounters are yet to come. This feature alone helps teachers prioritize instruction and intervene with additional resources when necessary.

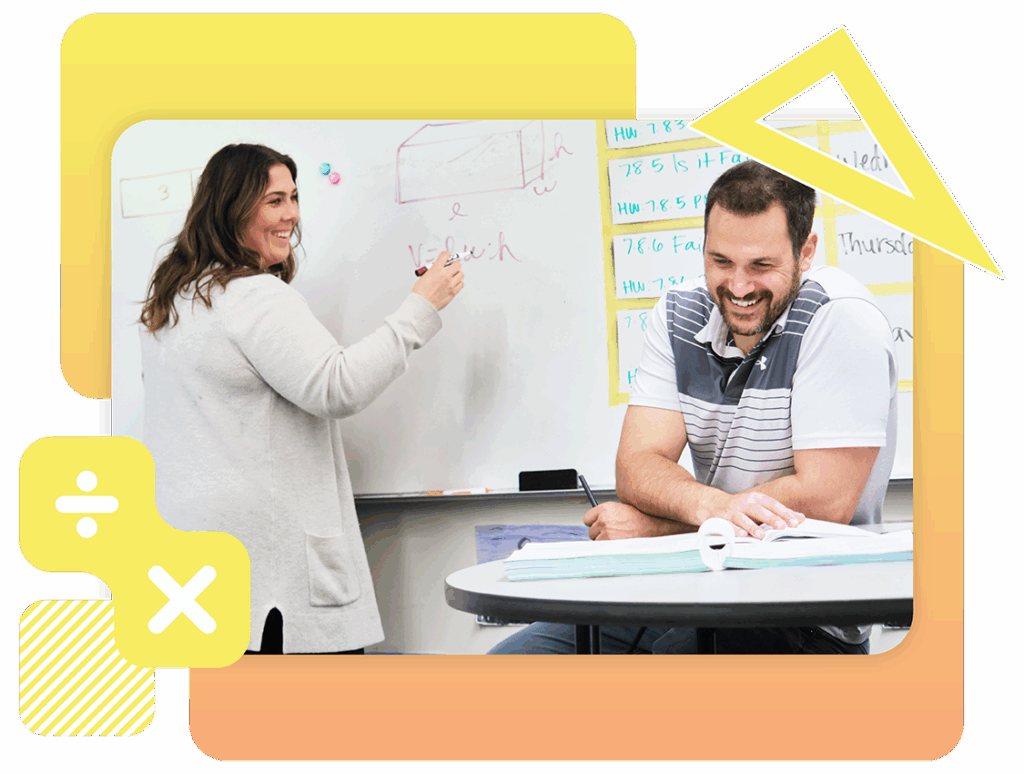

NYC webinar series

Figuring out how to implement a problem-based learning approach to mathematics can be fun—and challenging. Rest assured that you won’t be alone on this journey; Amplify will be by your side every step of the way. Our back-to-school math webinar series for K–8 administrators and teachers:

- Introduces the new NYC Solves initiative.

- Establishes the foundation for all educators to effectively understand and implement the NYCPS Shifts in Mathematics in their classrooms.

- Provides an overview of Amplify Desmos Math, the pre-approved NYCPS curriculum chosen to ensure that every school can successfully implement these math shifts and is supported with high-level, tailored professional development and coaching throughout the process.

Please see the specific webinars and the recordings below to learn more!

On-demand webinar 1

Would you like to learn more about the NYCPS Shifts in Mathematics and enhance your understanding of each of the five shifts?

Explore how the NYCPS math shifts are transforming mathematics education from a procedural approach to a more engaging, discoverable, and connected learning experience.

Listen to the Understanding the NYCPS Shifts in Mathematics session recording.

On-demand webinar 2

Let’s unpack the why, what, and how to unlock every student’s mathematical mind and build math proficiency for life! In this webinar, we discuss the power of teaching our children to be skilled mathematicians through a structured approach to problem-solving.

Listen to the Unlocking Mathematical Minds: A Structured Approach to Problem-Based Learning session recording.

On-demand webinar 3

For some educators, transitioning to problem-based learning might seem daunting. There’s often concern that the open-ended nature of the approach could derail students from achieving mathematical goals. However, by finding the right balance between open-ended opportunities and structured classroom activities, teachers can encourage students to share their thinking while meeting key learning targets. Uncover simple shifts that educators can implement to foster the perfect balance of open-ended student thinking and focus on mathematical instructional goals.

Listen to the Making the Shift to Problem-Based Learning session recording.

On-demand webinar 4

Amplify Desmos Math New York K–A1 is math that motivates! During this session recording, you’ll experience a grade 6 lesson that captures the essence of NYC Solves.

Listen to the Learn More and Experience Amplify Desmos Math LIVE, an NYCPS-Approved Math Curriculum session recording.

Looking for help?

Support is always within reach. Our team is dedicated to supporting you throughout your review. You can be reached at any time by emailing or calling us directly.

- Support pathways for NYC Core Orders

- Chat: Click the orange icon while logged in to get immediate help.

- Support Portal: Fill out this form, and we will get back to you as soon as possible.

- Phone: Call our toll-free NYC Support number: (888) 960-0380.

- Email: Send an email to AmplifyNYC@amplify.com.

S5-01. Investigating math anxiety in the classroom

Season 5 is here! This season, we’ll be talking all about math anxiety: what it is, what causes it, and what we can do to prevent or ease this anxiety in the math classroom. To launch this very important theme, we sat down with Dr. Gerardo Ramirez, associate professor of educational psychology at Ball State University.

As someone who’s been studying math anxiety for more than a decade, he had some interesting research and advice to share on why math anxiety affects so many students (and adults), and tips for how to start reducing it.

Listen now and don’t forget to grab your MTL study guide to track your learning and make the most of this episode!

Enjoy this episode and explore more from Math Teacher Lounge by visiting our main page.

Dan Meyer (00:01):

Hey, folks. Welcome back to Math Teacher Lounge. I’m one of your hosts, Dan Meyer.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (00:05):

And I am your other host. I’m Bethany Lockhart Johnson. Season five! Hello!

Dan Meyer (00:11):

Bethany, how are you doing? How have you been spending the long break between our recording sessions?

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (00:16):

As much as I loved sharing content from previous seasons, I am so thrilled that we’re back for season five. I have been, you know, chasing a toddler. I think he’s already tired of me saying, “Ooh, can we count that?” He’s like [sighs] “One two, one two.” Like, he’s done already.

Dan Meyer (00:36):

Too much counting. Yeah, I worry about that so much, that my love of mathematics might be perceived by my kids as smothering. Yeah, I worry about the same. We shared with you folks some bangers of reruns, in my humble opinion. Some great guests. But, we’ve been excited—me and Bethany—to hop back on the mics, on the ones and twos, and explore some new ideas together.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (01:01):

Well, I loved our season talking about joy in mathematics. And personally I could…like, we could turn this whole podcast into joy in mathematics. However, we’re kind of going a different route. Because if you ask folks why they don’t feel joy in mathematics, a lot of times at the root of that is some really intense math anxiety. So this whole season, we’re going to be delving into math anxiety. Exploring what it is, who has it, why do we think it happens, what do we think we can do about it, and how can we navigate through it, so that we can experience that joy in math? These are questions that we’re gonna explore over the course of the season. Dan Meyer, how do you feel about that?

Dan Meyer (01:49):

It feels big and it feels personal. I mean, as we shared in our math stories back from season…whatever it was, math anxiety was a huge part.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (01:59):

It was last season, Dan.

Dan Meyer (02:00):

Last…? I mean, who can remember? Big part of your journey. I’ve had some very punctuated but intense moments of anxiety in math class. And socially, we have built math up to be this incredibly powerful thing. You know, restricting movement on economic ladders, preventing people from getting into careers they want. Whether or not they have much to do with math class, math anxiety is a really large part of educational but also social life. And yeah, I’m really excited to explore it with you. We’re bringing on some really excellent guests. Some researchers, yes. But not just researchers! Also people who practice in the field and know firsthand what it looks like to resolve issues of anxiety with students.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (02:45):

Yeah, you’re right, Dan. My math story contained quite a bit of math anxiety, so I am particularly invested in this season. I mean, I still navigate math anxiety. And, you know, many of us do, and let’s talk about it. And let’s—I love that you reminded me. We’re gonna have a lot of great researchers all throughout the season, and a lot of times folks feel like the research happening, there’s sometimes a gap between researchers and what’s actually happening in the classroom. Not in all cases, but a lot of times. Right? And I remember a lot of conversation about the latest research when I was in grad school, but unless you’re actively studying something, sometimes we don’t know what’s happening. Right? We’re really focused on what’s happening right in front of us in our classroom. So let’s take some of that research; let’s break it down; let’s talk to some of the folks who are thinking about this for the bulk of their day, right?

Dan Meyer (03:41):

Yep. So we got our first guest coming up in a moment here.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (03:45):

So to kick off this season, we’re starting episode one by talking to Dr. Gerardo Ramirez, Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at Ball State University. And he’s been researching math anxiety for more than a decade. He’s worked with so many amazing folks in the field. He’s worked with students, he’s worked with teachers, with educators…I’m just so excited to talk to him. If you look up math anxiety, you see his name as one of the folks who is really thinking about this at so many different angles, and we get to talk to him. So enjoy our conversation with Dr. Gerardo Ramirez.

Dan Meyer (04:29):

We are so excited to have Dr. Gerardo Ramirez on the show with us. Dr. Ramirez is an Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at Ball State University. Thanks so much for joining us.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (04:40):

Yeah, thank you for inviting me to talk about math anxiety.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (04:43):

So with your interview, Dr. Ramirez, we are actually launching the season. We’re gonna be talking about all different aspects of math anxiety, and it feels pretty perfect that you are first guest of the season, because of the sheer breadth of research and conversations you’ve had about math anxiety. Could you start us off kind of telling us a story of how did you get interested in studying math anxiety? Or why, you know, why did you dive into this topic that, you know, I think a lot of folks might…like, if you’re on a plane, and you say, “Oh, I study math anxiety,” what kind of reaction are you gonna get?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (05:24):

Oh, sure. Yeah. I think most people are actually very interested because they all have their own story about feeling anxious about math, or just being anxious about evaluation situations that involve math. And, yeah, they wanna share those stories. People feel quite comfortable talking about their anxiety about math, for some reason. But for me, I started off, when I was in undergrad, I was studying to take the GRE quiz. I was hoping to go into a psych program. But I wasn’t exactly sure what direction yet. As I took some of the practice tests, there’s some situations in which I was very nervous about taking the practice test. And I just noticed that I did really poorly on some of these exams. And so I became very interested in issues like choking under pressure, which means when you underperform relative to what you expected to perform. And so, as I was researching these issues, I started to come across this whole field of math anxiety. And I saw that while there are some people who choke under pressure during tests, there are other people who just have a strong general fear of mathematics.

Dan Meyer (06:29):

That’s really helpful. I can imagine you’re doing a lot of free psychology sessions, free therapy for people on airplanes when they bring to you their own stories of math. So let’s thank you for your service in that sense. I’m super-curious. So Bethany and I have both taught math. We both have seen firsthand what it looks like when a student is anxious in math class, though maybe we don’t have kind of the clinical language to describe it. And I’m curious, from a clinical sense, how do we define math anxiety?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (06:57):

Sure. So first off, math anxiety is not something that you would find in the DSM, for instance. But we generally define that as a fear or apprehension to situations that involve math. So it doesn’t have to necessarily be educational situations. It could be someone asks you a math-related question during a party, or you have to calculate the tip at a restaurant, for instance. It doesn’t have to be about schooling situations, although that’s obviously where it seems to matter a lot for many people. So it is basically a fear or apprehension to situations that involve math. And I think distinguishing the term “fear” from “anxiety” is really important here. A lot of times people use those terms interchangeably, and the term “fear” is obviously within our definition of math anxiety. But oftentimes what differentiates anxiety from fear is that, anxiety is—think of it like a recipe. Anxiety is fear plus a little bit of unknown. OK? So if, for instance, if you hated snakes, and they threw a snake at you, you’d be in intense fear. Whereas if you hated snakes and they said, “There is a snake in the room, but I’m not gonna tell you where,” that’s gonna cause anxiety. And so the reason why we call it math anxiety is because a lot of times people experience this fear for a possible unknown future that involves math or possible unknown evaluations that people might have about your competence, because of math. And so for a lot of kids, they feel anxious about how they’re gonna do on a test or whether they’re gonna be able to pass a class or whether they’ll be able to understand what you’re saying in your lessons, for instance. And so the anxiety component really gets at fear of something that’s unknown, but related to mathematics situations.

Dan Meyer (08:47):

Math is somewhere in the ceiling right now. Perhaps I might be surprised with a math situation!

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (08:52):

Yeah. yep.

Dan Meyer (08:52):

So I have this tendency to assume that every other subject that we teach has it better and easier than math does. It’s not true. I know this is not true. But I’m kind of curious here. Is math anxiety, like, part of a general just set of anxiety around schooling itself? Like, is there a reading anxiety, a writing anxiety, and does that all just flow from the same kind of fount of anxiety around schooling or situations about learning? And what makes math special in this regard? If it is its own special anxiety, for instance?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (09:27):

There are different…so some people obviously suffer from generalized anxiety. Right? And so they would, you know, feel anxious both for evaluative and non-evaluative situations. But in the research that we’ve done and that other people have done, there are differences between things like reading anxiety, math anxiety; I’ve also studied spatial and creativity anxiety. A lot of times what we’re trying to do in these studies is we measure all of the above, and we try to show that, look, math anxiety predicts math situations above and beyond these other things. So yeah, we definitely distinguish those things. And so what’s special about math is that, well, I think the symbolic nature is a big part of it. The abstract symbolic nature is just not as tangible to students. They can’t touch it. And so it doesn’t allow ’em to use their full cognitive faculties to play with it, as you might see, for instance, in science. Or it doesn’t allow people to relate math to their own interests the way you might see, for instance, in English. So maybe I hate reading novels, but I’m interested in zombies and you give me a book on zombies, well, ok, great, you’ve connected my personal assets to the topic. Whereas with math, either that’s harder to do or instructors don’t do such a good job of setting that connection up.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (10:46):

Also, I think, you know, I’ve heard of students being really anxious, let’s say, during a reading session, when teachers used to do—hopefully they’re still not doing it—the popcorn reading, where you just randomly call on a student to read out a sentence. Right? But you don’t really hear students or adults talking about, “Oh, no, no, no, I don’t read; I don’t mess with reading.” You know? Whereas with math, you do hear, “Oh, I’m not a math person. Oh no, no, no, don’t ask me any math questions.” And that is such a distinction.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (11:18):

Yeah. And I think a lot of that’s because it’s just so common. As an adult, to be nervous about reading is kind of an uncommon thing. So people feel a stigma around admitting that. But math is something that everyone feels like they’re inadequate in. And so there’s a lot of comfort in telling you how they’re just one of the many people who don’t like math. And that, you know, can have a lot of different consequences and outcomes. I think on the one hand, I think for a lot of kids it becomes a normalized message that if you fear math, that’s OK, join the club. Right? But we have to be careful about that, ’cause a lot of math anxiety researchers will oftentimes say, part of what leads to math anxiety is adults normalizing that it’s OK to be scared of math. So I think a lot of times adults, teachers, for instance, math teachers, they’ll tell kids, “You know, if you’re scared, that’s OK.” And so a lot of the math anxiety community says, “No, no, no, you’re not supposed to do that.” But my recent view is different. I view that as a form of validation. Because math is hard. And so telling kids, “Hey, look, it’s actually easy if you just try,” I don’t think that’s true. It’s actually just hard. And I think even if it was easy, to the kid, it feels hard! And I think something that’s not really well-studied right now in our field is the value of validating people’s math negative math experiences. We don’t want to validate that, ’cause we think that we’re gonna reinforce that. But actually, I think the opposite. I think when you validate people’s negative math experiences, it helps ’em to feel that they can handle it. They can start to take control over their own emotions.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (12:52):

I love that. And I, I actually, I think that’s so powerful, what you’re talking about, that validation. I taught kindergarten, and I vividly remember being in a parent-teacher conference and that parent saying, “Oh, I wasn’t a math person either,” right? Or, you know, their language and their experience with their own math schooling, their anxiety about math was actually impacting their students’ experience of math. Or the conversation that, when I would go to talk about a math assessment, let’s say, you could see the parent actually tensing up. And there was this moment of validation, that I felt like we needed to make space for that in the conversation with the parents, right?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (13:38):

Yeah.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (13:38):

Like, this is a real thing. And we are working on teaching students that math is something that gets to—your experience with math gets to look all sorts of different ways. And it’s OK if we, you know, make a mistake, or if we kind of only get this part, but we’ve really got that part. Or let’s talk about it; let’s write about it. So I really feel like that that validation is something that’s so missing. And instead of the validation, like you said, you see folks being like, “Oh yeah, me neither. I’m not a math person either.” Right?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (14:10):

Yeah. I think…part of the reason why people are comfortable sharing this because they’re looking for validation also. When they say, “Oh, I’m not a math person,” you know, I think they’re hoping that, you’ll say like, “Yeah, me neither,” or “Of course not, ’cause math is terrible.” Right? They’re looking for validation, not to reinforce their perspective, but to feel that it’s OK not to be a math person. And I think that’s one of the techniques that I’m trying to work on in my research right now, is to provide evidence that actually people will work harder when you validate their math experience. You don’t have to tell them a positive story per se. If your current story is “Math is hard and I’m very, very anxious; I’m scared,” then we can just validate that and help you work through that. And it actually will strengthen our relationships. Because if you’re a student and you’re struggling with math and I tell you, “Yeah, it’s hard; it’s OK to struggle with math,” that makes you feel seen. And that’s gonna lead you to want to ask me more for help, because I’m someone who understands you. And that’s a great, you know, remediation opportunity.

Dan Meyer (15:14):

A common thread that I think I’m seeing here in several answers is that math sometimes asks students to disassociate part of themselves. Where success in math oftentimes means working from an a level of abstraction with symbols, like you said, that can feel alien. Like, who am I here? And in the same way, I love that you’re proposing we validate and reassociate people with a very deeply felt part of themselves that is anxious about mathematics.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (15:44):

Yeah. I mean, I think that’s what validation’s supposed to do, right? So a lot of us, when we feel these strong emotions, we wonder, “Is this even a real thing? Are other people feeling this? Is there something wrong with me?” So we feel the emotions, but we can’t actually deal with them, because we wonder if they’re legitimate. And so when someone says, like, “Yeah, this is hard,” it crystallizes that emotion. And once something is made real, you can actually choose how you want to deal with it. Some kids are gonna deal with it by staying anxious. But some people are gonna choose to deal with it by saying, “Well, there’s nothing I can do about it now; I have to take this math test, so I’m just gonna think positive.” And that’s great. If the kid can end up saying that to themselves, that’s much more effective than me telling the kid, “Hey, you just gotta think positive. You’re gonna start the test anyway.” And so we want the kid to make meaning of their experience, and the way we do that is by crystallizing their emotions through validation.

Dan Meyer (16:36):

Yeah. I love that. And so what you’re proposing there, I think, sounds like, a solution, like a post-talk solution after students are feeling anxiety.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (16:43):

Yes.

Dan Meyer (16:43):

To validate and empathize.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (16:45):

Yes.

Dan Meyer (16:45):

And over the course of our season, we hope to explore a lot about solutions to math anxiety that are preventative, that reduce the odds of anxiety arising, through instruction and curriculum, before it arises. And I’m just wondering if you’ve seen anything that would hint at either specific or general words of wisdom you wanna share with the educators, about not just addressing it after the fact, but preventing math anxiety before it arises?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (17:14):

To be honest, at this point, I haven’t seen enough evidence for me to recommend anything concretely as an intervention for math anxiety, or an intervention to prevent its development. All I can really do here is rely a lot on the more broad cognitive-behavioral research on anxiety, which says that one of the ways we prevent people from developing anxiety is by helping them to make more positive appraisals of challenge situations. So a lot of times, when kids are challenged, they don’t know how to interpret that. “What does it mean that I’m struggling with this thing?” And so that’s where I think a lot of teachers can help students’ interpretations of that. ‘Cause if you leave kids to their own devices, they’re gonna think, “I’m struggling because I’m stupid. I’m struggling because I’m not good enough. I’m struggling because my dad is right; I’m gonna be a failure.” You know? They’re going to impose an interpretation to a challenge situation regardless. And so, as teachers, one thing we can do is we can help shape that interpretation and say, “What does it mean to struggle with math? People will say it means you’re stupid. That’s one interpretation. What’s another one? It means that your brain is working really hard to think through something. That’s another interpretation. What’s better? What do you think is more helpful?” And then, helping students to see how interpretations matter to how you ultimately feel about something. And that’s a very metacognitive way of thinking about things. So yeah, I would say that one way to prevent it is to help students to take more positive interpretations of their experience. But another way, and I think a more successful way, I think, is to give students early experiences where they feel efficacious dealing with math. One of the ways you do that, for instance, is by obviously making sure that the students understand the material—but that’s obvious; people are trying to do that. One of my favorite recommendations is to keep reassigning assignments, the same exact assignment, for, say, three weeks, back-to-back. So if in week one you do the homework assignment, you do OK, you don’t do so great, when week two you do it, you give the exact same assignment, and now the student can see like, “Wow, OK, this was much easier.” And then, week three, you give the exact same assignment; now the kid’s feeling really confident. And the reason why that’s great is because it helps kids to see that they’re growing in confidence. A lot of times kids don’t get to see that because we’re constantly throwing new assessments at them. And so they’re never seeing that growth. All they’re seeing is a new challenge, a new challenge, a new challenge. So I think we need to set up situations where they can feel that they’re growing, when we keep the assessment static. That can be a formative assessment, for instance—doesn’t have to be a summative assessment.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (19:55):

That feels so powerful and it feels like it really connects to that validation piece, right? We are actually helping to create a culture in our math classroom where we might struggle with something, but we keep revisiting it. And it’s not so much to reach mastery, but as Dr. Megan Franke — we talked to her about this partial understanding and about pulling on those threads of things that you do understand, so that you can build your confidence…build, not just confidence, but build your…I guess, kind of get your footing, right? You’re saying, “Well, I do understand this. I see how this works.” And if I’m revisiting an assignment, I feel like that would give me permission to like, “Hey, I don’t have to have this figured out on the first pass. You know?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (20:44):

Yes, yes. Yeah. I mean, I’m gonna give you a silly analogy, but I think it works. You know, a lot of times people will have nightmares, right? And they’ll keep having the same nightmare over and over again, right? And so one reason that we suspect this happens is because they haven’t worked through whatever that nightmare’s supposed to be about. So if, say, I’m scared of driving, I may be having the same dream about driving and crashing over and over. And we keep having these nightmares. And I think math anxiety is kind of like a waking nightmare, where you keep rehashing something because you haven’t had the chance to finally address that dragon. You know? And so if someone was having a lot of fear over driving, then one behavioral approach would be, you know, to work with a therapist to actually get behind the wheel and maybe drive around the same track over and over until you feel comfortable at that, and then the nightmares stop. Well, the same thing is true, I think, about math, math and math anxiety, is that you wanna give people these opportunities to feel confident by going back to that original experience that caused them to feel anxious, and saying, “This one assignment that we did in week three that really freaked you out, let’s try it again now in week five. How was that?” “Yeah, it wasn’t so bad. It was still kind of annoying.” “OK, we’ll we’ll come back to it.” “Now it’s week seven. Now let’s go back to that assignment. How is it now?” “That’s actually…it wasn’t that terrible.” And that gives people the opportunity to reflect on how they’ve grown past that nightmare.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (22:05):

I have to say, Dan talked about you being like a therapist. I’m like, wait, “How did you know, Dr. Ramirez? I did have this recurring dream! I did! And I had to face it. No, but I had such intense math anxiety in high school and it was debilitating. And the biggest thing for me, I thought I was the only one. I thought there was something wrong with me. I thought, “Why can’t I figure this out?” There wasn’t a conversation about “Here are some tools,” or “Here are some, some, some…”. Like, “This is OK, for you to feel scared about this or overwhelmed!”

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (22:41):

Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (22:42):

You know, I think often when we talk about how widespread math anxiety is, I think a lot of folks automatically jump to high schoolers or college students avoiding math courses. But we see this in really young kids.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (22:56):

Yeah. So people are…people are just constantly making meaning of themselves, regardless of the age range. And that’s true even with young kids; they are trying to figure out who they are. Right? And so one of the things you see oftentimes with young kids is you ask ’em, “What are you good at?” And they say, “Everything!” And that’s their attempt to, you know, make meaning of themselves. But sometimes they’re not good at everything. Sometimes they actually struggle in math. And I think even early on, they have to make meaning of that. They say, “Well, I’m good at everything except math.” And how do you make sense of that? Well, why not math? “Oh, because math is terrible. It’s not for everybody. You know, it’s not something that I like.” And so, yeah, in a lot of the studies that we did early on, we basically went into these first-grade classrooms with the purpose of trying to assess whether we can actually show variability in kids’ math anxiety, even early on. In other other words, do kids even report feeling anxious about math situations? Or do they tell us that they’re great at everything? And what we found was that in fact, a good chunk of kids are, again, perfectly willing to tell you that “No, certain situations involving math make me very anxious.” Counting or addition, or doing a problem on the board. And the way we do that is by—I think there are probably more sophisticated ways that can be done, but this is the best we have at this point—is we go in there and we ask them, we show them a bunch of smiley faces and anxious faces. And we say, “I want you to tell me how you feel about these different situations that involve math.” And so we say, “If you feel kind of nervous, I want you to point to this face. If you feel very nervous, point to this face.” And we basically will read to them situations. We’ll say, “How would you feel if your teacher asked you to open up your new math textbook and you saw all the numbers inside of it?” And they’ll point to the really nervous face. So right now, those are some of the more reliable assessments for math anxiety among young kids. And that work showed us that even young kids are self-reporting math anxiety.

Dan Meyer (24:51):

Obviously this is worth our study, because we would hope people would not feel anxious in general, and especially if we have a mandated…kids are mandated to be in math classes for their entire childhood. So I see the need for this study, these studies. I’m curious: What are the consequences, though? Like what, what correlates with math anxiety? What are other reasons why we should care about math anxiety and work to remediate it?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (25:16):

Oh, sure. So it correlates with their actual math performance. It can correlate when they choose to do homework. Right? So a lot of times, the parents report having to fight with their kids over math homework a lot. And you also oftentimes see a lot of frustration over mathematics specifically. And so it can, you know, not only affect their academic ongoing outcomes, like math tests and math assignments, but it can also affect their relationship with their parents. So if every time you come home, your dad’s screaming at you because you haven’t done your math homework, and when he asks you to solve the problem in front of them, you don’t remember, ’cause you were checked out, ’cause you’re so stressed out, that’s gonna cause a really negative experience. You know, a lot of times people grow up and they still remember their dad screaming at them over the math homework. You know, it’ll affect your relationship with your teacher. So if you’re making me feel incompetent, if you’re stressing me out, you’re not the kind of person I wanna come to for help. So it can predict relational outcomes as well as academic outcomes. And down the line, of course, when it affects students’ opportunities to get into things like AP classes, it affects students standardized test performance and their choice of colleges, as well as scholarship opportunities.

Dan Meyer (26:29):

Once you show that it correlates to performance, then that opens up a whole range of other correlations that are pretty important, it sounds like. Whether that’s career options or, you know, post-secondary education and the like.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (26:40):

Yeah. And a lot of times, when people are choosing a career at college, a lot of times students will make a decision specifically based on what career has less math requirements or less math courses. So I think this finding needs to be verified further. But, there’s some studies showing that, for instance, elementary ed teachers, one factor that feeds into the decision to go into elementary ed is the math requirements are very low in elementary ed. So that can…obviously it’s not what we wanna hear, because these are our first formal math teachers, right? For our kids.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (27:16):

It feels so powerful, the impact that math anxiety can have, not only while you’re in, let’s say, elementary school, high middle school, high school, but then the impacts beyond that in terms of your career. And I shared this last season, when we talked about our personal math story, but I know when I was navigating the deepest part of my math anxiety, I really felt like, maybe this is a reason I can’t be an elementary school teacher. Because I was so worried that I wouldn’t be able…not that I wouldn’t understand the math for fourth grade, fifth grade, but that there was something about my ability to teach it or understand it or develop a love and passion for it that I wouldn’t be able to do. And I really had to reclaim it in my own way. But, you know, something that I think is so powerful about your research is just the applicability — not only to the field of mathematics, but folks’ everyday lives. And the way that you have talked in the past about math being a gatekeeper…I have a family member who, brilliant American Sign Language interpreter. I mean, amazing. Like a dance with her fingers. I could just watch it all day. And she actually didn’t complete the program because she couldn’t complete the math requirements. And I remember talking to her about like, “Well, have you gone to the free tutoring? Have you gone to, you know, this or that?” But it was a paralyzing fear, you know? So Dr. Ramirez, what do you wish educators understood about math anxiety? Or the research about math anxiety? Or maybe even the general public at large, what do you wish folks understood about math anxiety?

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (28:58):

Oh, I think that a lot of students, they struggle with math. And I think we wanna normalize that struggle as much as possible. We want to create a culture where it’s OK to do math slow; it’s ok to take your time. And I know that’s not possible with a lot of these requirements that a lot of math teachers have to do. But I think if we want to prevent math anxiety, we have to create opportunities to tell better stories. So that’s ultimately what I tell people is, why do people develop math anxiety? Because they had experiences that challenged their competency and they told a negative story. And so making space to reflect in math classrooms about what does it mean to go slow in math, or what does it mean to make mistakes, and then helping kids to tell better stories, I think it’s really the best thing we can do as math educators. ‘Cause you know, your job is not to be a therapist ultimately. You know, there’s only so much math teachers can do. But I think one of the most powerful things we can create is setting up students’ experiences where they feel confident, and they can tell better stories, so they can have better dreams about math.

Dan Meyer (30:06):

Really appreciate this introduction to math anxiety. It’s been a fantastic kickoff to our season. Dr. Ramirez, thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez (30:14):

Sure. Thank you.

Dan Meyer (30:16):

Thank you folks so much for listening to that conversation with Dr. Gerardo Ramirez, Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at Ball State University.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (30:25):

Dan, OK, if not for your frantic signaling, I would’ve probably asked another 20 questions. I need to know what you thought .

Dan Meyer (30:34):

I found it interesting at all points. And especially I think I started to understand a little bit better where the anxiety comes from for some students. I got a little bit here, which is that I think math, more than other disciplines, involves alienation. Check that word. You like that? Alienation? I’m into it. I’m feeling it. It’s like…to get good at math, to be successful in math, you gotta, as a kid, lose your attachment to the world you understand. And I mean, “got to” as in like, “you are asked to” — many times, unfortunately, by curriculum and instruction. Which is to say, you’re turning things you can hold onto into numerals. Right? You’re turning the world and its patterns that you can see and touch into Xs and Ys. And I just don’t know that other disciplines deal with that as much. Maybe I’m wrong and just guilty of, you know, “grass is always greener” syndrome here. But I think that’s an experience that kids have in math. And I thought that Dr. Ramirez got at that when he’s talking about the need to validate a student’s experience of anxiety. Like, in treating anxiety, sometimes we alienate people further by just like saying, “Oh, no, no, no, it’s just like, you need to, you know, drill yourself more, practice more,” and kind of invalidate that. So this feeling of alienation, I think permeates a lot of math instruction. I’m looking forward to learning more about that with our future episodes

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (32:00):

Alienation. That’s interesting. I definitely felt, I definitely felt isolated and alone many times in my math journey, when I was having my…you know, in high school, when I was feeling like, “Clearly everyone can look at tan, sign, cosign, and that means something to them.” Right? I think it’s really interesting, because I’m thinking about the other disciplines; I’m running through them, and I’m like, even in science, which can seem abstract, so oftentimes there’s these experiments that accompany these concepts, where you’re like, “Look at this concept made real in front of you.” Right? . And so yeah, that’s really interesting.

Dan Meyer (32:39):

You’re always one step away from blowing something up! Or, you know, dissecting something that’s tangible to you.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (32:46):

Yeah. That’s really interesting. I did really love how he brought up the abstract. And how, I think, even validating it…he talked so much about validation. Which to me was like, YES. If somebody just said, “Hey, it’s not only possible to have math anxiety, but it also doesn’t mean that you don’t belong here.” If somebody had said that, it would’ve literally changed the trajectory, you know? And I wonder what those conversations could look like in our classrooms, where teachers celebrate that. Like, WHOA, this is a new way to think of this. This is a new way. Asking how many, or what do you notice for this image, through a mathematical lens, or looking…we talked to Alison Hintz and Antony Smith, like mathematizing books, like looking through these lenses — it’s an invitation to step into this other world, right? But there’s not only one way to do it. And I think oftentimes it’s like that anxiety of “Am I gonna say the right thing?” or “Am I gonna notice the right thing?” Right? How do we create that space more, where there’s so many possibilities and we want kiddos to notice what they notice, right?

Dan Meyer (33:54):

You gotta become a certain kind of person to be successful in math class. I feel like is part of the implied deal. Where you’ve gotta—like how you said—say a certain thing or think about a certain thing a certain kind of way. You’re trying to become someone who is not necessarily you. Which I think is fundamentally an experience of alienation, separating you from important parts of yourself.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (34:19):

I will never, ever dive into mathematics on the scale and level that you have with your PhD. You understand math in a way that my brain just…I won’t get there, right? And yet I’m allowed to call myself a mathematician, with all of my deep dives in elementary math and my love of early numeracy and thinking about how we start thinking about counting and numbers. Right? It’s like, if we make more space for what mathematicians can look like, and what is your personal relationship with math…I mean, that to me feels really exciting. ‘Cause I think we both have something to offer each other.

Dan Meyer (35:03):

I think I have never found early math more interesting than when I talk to early math educators. And learn just like all the different ways that students come to understand a concept that I had thought was simple. Like addition of whole numbers. Whoa! There’s a lot of ways kids do that work, and their brains think those thoughts. And, yeah. That’s a good word there you’re offering us and our listeners.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (35:27):

Yeah. Yeah. I’m really excited about this season. I think there’s — again, there’s no way we’re gonna cover all facets of math anxiety. But I think having the chance to explore it over the course of a season is going to be really fascinating. And really, I hope, destigmatize it and open up the conversation for our listeners. And, you know, if you listeners…we wanna know what you thought of this episode. Do you have any particular questions? Do you have questions related to math anxiety? Questions related to this episode? We are in development for this season, so we’re gonna do our best to get those questions answered. You can keep in touch with us in our Facebook discussion group, Math Teacher Lounge Community, and on Twitter at MTLshow.

Dan Meyer (36:14):

Next time, we’re gonna go deeper into the causes and consequences of math anxiety.

Dr. Erin Maloney (36:20):

It’s not just the case that people who are bad at math are anxious about it. It’s actually that the anxiety itself can cause you to do worse in math. And that for me is really exciting, ’cause it means that if we can change your mindset, then we can really set you on a path with several more options available to you.

Dan Meyer (36:41):

Til next time folks,

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (36:41):

Bye.

Stay connected!

Join our community and get new episodes every other Tuesday!

We’ll also share new and exciting free resources for your classroom every month.

Meet the guest

Dr. Gerardo Ramirez obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, where he studied the role of teachers and parents in shaping the math attitudes of their students, as well as reappraisal techniques to help students cope with anxiety during testing situations.

Dr. Ramirez is currently an associate professor at Ball State, where he examines the role of frustration, empathy, and cultural capital in shaping students’ success and persistence.

About Math Teacher Lounge

Math Teacher Lounge is a biweekly podcast created specifically for K–12 math educators. In each episode co-hosts Bethany Lockhart Johnson (@lockhartedu) and Dan Meyer (@ddmeyer) chat with guests, taking a deep dive into the math and educational topics you care about.

Join the Math Teacher Lounge Facebook group to continue the conversation, view exclusive content, interact with fellow educators, participate in giveaways, and more!

You might also like:

S4 – 04. Dear Math

In this episode, Bethany and Dan chat with Sarah Strong and Gigi Butterfield, authors of Dear Math: Why Kids Hate Math and What Teachers Can Do About It. Listen in as they chat about their experiences with finding joy in math, and how their passion helped them tell the stories of other students’ journeys to find (or not find!) joy in math.

Explore more from Math Teacher Lounge by visiting our main page.

Dan Meyer (00:01):

Hey folks, welcome back to Math Teacher Lounge. My name is Dan Meyer.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (00:05):

And I’m Bethany Lockhart Johnson.

Dan Meyer (00:06):

Bethany, it’s been fantastic to see you. It’s been a long while. I feel like [it’s been] since NCTM and our last episode, where we compared the best teacher from movies and TV, crowning the winner Tina Faye from Mean Girls, is a huge, huge episode. It’s good to see you back.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (00:20):

Didn’t see her coming, but it’d be so fun to be in person. And the energy in that room was, I mean, if you listeners, if you heard that episode, we had some very, very passionate opinions about which teacher was best represented. And we’ve heard from a lot of you that we left a ton of people out. We know, and you know, it’s been great to hear your opinion and your defense of Ms. Frizzle. So, thank you for that. <laugh>

Dan Meyer (00:50):

I apologize for nothing. We’re super excited right now to bring to you folks the first post-NCTM episode. We have a couple of authors, a couple of published authors on the call here. And they, they got a really fun premise for a book. They have, I think, maybe one of the most interesting data sets out there. There’s lots of data out there that’s quantitative, you know, survey data or assessment data and who-knows-what percentages. And they’ve got a set of data that’s just super qualitative, but really dives deep into the beating heart and soul of students as it relates to mathematics. Especially because this season is all about joy in math, how students have it, why they don’t sometimes. And what we can do about that. First up, Sarah Strong is a co-author of the book Dear Math. Sarah loves hearing people’s math stories. I’ve known Sarah first as a math and science teacher in grade six through 12, and a teacher developer at High Tech High in San Diego, a school that’s very innovative and project based and very exciting. And so Sarah’s on as a co-author. And Gigi Butterfield is also a very talented mathematician. And, you know, someone that I have learned from. So I consider Gigi a math teacher-educator as well, coincidentally, [as] one of Sarah’s students! So this is a fun project where Sarah and Gigi are teacher and student and co-authored a book called Dear Math. And Gigi’s now a student, a screenwriting major at Loyola Marymount University. So please, welcome on, great to have you folks, Gigi and Sarah.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (02:28):

Welcome, you two. We’re so glad to have you in the Lounge.

Sarah Strong (02:32):

Yay. Thanks for having us.

Gigi Butterfield (02:34):

Yeah, happy to be here.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (02:35):

So the full title [is] Dear Math: Why Kids Hate Math and What Teachers Can Do about It, and as I was reading this out and about in the wilds <laugh>, you know, it was really interesting. Like I’m sitting in a waiting room and somebody starts to talk about their math experience, which, you know, Dan, you know, I love to talk to people. Actually, this season, Sarah, Gigi, we are actually starting all of our episodes, and we actually had a whole episode about this, about Dan’s math story, my math story. We’re asking all of our guests to share their math story. As I was reading Dear Math, I also felt like I got to hear more about your math journey as well as bits and pieces of the students in your class from their ‘Dear math’ letters. It was really wonderful. And so I was like, oh, I wanna hear their math story. So would you share your math story with us, as little or as a lot as you would like to?

Sarah Strong (03:35):

Well, we should have Gigi go first because this book is all about centering student voices. And so I always feel like we need to start by listening to the students. And Gigi here is the student, so Gigi.

Gigi Butterfield (03:47):

Wow, thanks Sarah. I feel very centered <laugh>. Um, so <laugh> my math story as a young student, I quite ‘liked math.’ I put that in quotations that I liked math, and that was because I pretty much thought that I liked it because I was told that I was good at it. I could complete the math assignments that my teachers gave to me pretty easily and pretty hastily. And so that made me feel really good about myself. And then I’d get a big red A+ and that’d make me feel even better about myself. And so I was like, I love math. Math is awesome cuz I’m awesome at it. And this formed what, if you read the book, you’ll see Sarah and I kind of coined a fraudulent fondness of mathematics in that, oh, ‘I think that I like this thing because I don’t really understand it that much, but I understand what I need to understand to gain validation from my teachers and peers.’ And so that’s kind of the attitude I was heading into middle school with. And it carried for the first couple years. And then in eighth grade I had a math test that I failed, like, four times in a row. And that was the first time I had really experienced failure within the math classroom. And it was super hard for me. And it ended up being, for a brief time, very detrimental to my relationship with math in that I was like, well, ‘The reason I loved this is because I was good at it and I’m not good at it, so I hate it. So I hate math so much, it’s my least favorite thing.’ And then I got to high school with that attitude, very different than the one I was entering middle school with, and then I had Sarah Strong as my math teacher. And throughout that first year and then a subsequent three more years where she was my math teacher, I learned that my fraudulent fondness had been just that, it had been completely fraudulent, and that the reasons I liked math, the pillars of what made me good, speed and accuracy, void of any real contextual understanding, were super arbitrary. And they were actually the reason that I wasn’t able to deeply enjoy math at all because I wasn’t coming at it with curiosity or creativity or any sense of relating it to my own life in the greater world. And then I learned how to do those things and I learned how to get excited about math, even when I wasn’t able to do it really easily or really quickly. And then I started to love math and I still love math today. So that’s what I would say my math story is.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (06:36):

I love it. It’s so interesting to hear that you have such a clear, and in the book you talk about it, too, this reflective sense, you’re able to reflect on what that test meant. Like it could have gone a very different way, right? Oh, which, folks, we should say that Gigi was in Sarah’s class for four years. It sounds like this relationship you had was really healing.

Gigi Butterfield (07:00):

Yeah, it was amazing. I was like the luckiest high schooler ever.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (07:04):

For reals. Yeah, that’s beautiful. And it’s so cool to hear that you were able to transform that and your relationship really evolved, you know? It evolved.

Dan Meyer (07:15):

I love your comment about how, ‘Now I realize there’s gonna be tough times, and that’s not an indication of failure or a fraud.’ It’s actually a very real part about relationships with humans and with subjects like math as well. It’s super fun to hear. I’d love to hear from Sarah. It’s so wild that you two have been a part of each other’s math story, to a significant degree. How would you summarize your math story?

Sarah Strong (07:38):

Certainly Gigi was a player in my ongoing math story as an adult. And I think that’s also a part of it, is we all have continually evolving and emerging stories of who we are as math teachers, but my math story is kind of congruent to Gigi’s and that’s part of what’s inspired this book is the phrase Gigi used in her ‘Dear math’ letter, fraudulent fondness, I had never thought of that beautiful alliterative phrase before. And I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s what I felt.’ And I had called it a fixed mindset, or all of these other things, but calling it fraudulent fondness was so poignant to me that I couldn’t get it outta my head, and we just kept talking about it. And I think my fraudulent fondness started probably in high school. Before high school I think I was just really stressed out about math, because I thought I had to do really good at it and get things really right really fast or else I was dumb. So this was part of the fixed mindset piece. And so I wouldn’t say I loved it in elementary school, I more felt the weight of it. And I remember especially timed tests, which we always hear about a lot. I just remember sweating and shaking and being like, if I don’t get this the fastest I am a failure, I will cry. And that’s not really setting yourself up to love a thing. So I was, it was a bit fraught and stressful, but then in high school I had this belief that I had to keep being good at it, but I started getting a lot of positive feedback from tests and quizzes and teachers, that was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re so great at this. You should be in this class and look, you moved into Algebra Two as a freshman. Wow. Who takes Algebra Two as a freshman? You must be so smart.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, I am so smart.’ But that is sort of an anchor for fraudulent fondness as, ‘I like math because I’m in Algebra Two as a freshman.’ That has nothing to do with being mathematical at all, necessarily. My senior year, my calculus teacher knew I was thinking of becoming a math teacher, so she invited me to support her for my math class that year in one of the freshman math classes with her.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (09:54):

Wow.

Sarah Strong (09:55):

So I was like a teacher’s aid as a senior. And it was there that I think I started to break down some of my assumptions of what it was to be mathematical and start realizing, I never had the term fraudulent fondness, but realizing that I didn’t fully understand or grasp what mathematics was because the students in her ninth-grade class, I was getting to look at their work <laugh>. I was stamping their warmups, and there [were] so many interesting ideas on there that I had not confronted in my own math journey cuz I was really sucked into my, like, ‘Hey, here is my work. And I checked my answer on the back and it was right.’ I hadn’t seen different ways of thinking about mathematics and my eyes were opened and that made me wanna become a math teacher even more. I’d say throughout college I did a lot of collaborating and working with others and really developed a keen excitement for different ways of thinking about math and then becoming a teacher, I mean that’s the cornucopia, unique and creative math ideas are there in front of your face every day. And so I just thought it was the most fun thing to do. I started in sixth grade, to listen to what the students were saying and their conception of things and try to make sense of their thinking.

Dan Meyer (11:18):

There’s something so joyful from the student’s perspective of experiencing a knowledgeable other as being very curious about what they’re thinking, whether it’s right or wrong, maybe especially if it’s wrong, I just, I think about that and how you’ve been a part of people’s joy in math class from even when you were a math student, as a pretty special bullet on your resume. Thanks for sharing all that. I would love for you to explain to the audience what the ‘Dear math’ assignment is. Would you paint a picture of what the ‘Dear math’ assignment was?

Sarah Strong (11:48):

Yeah, the ‘Dear math’ assignment was birthed out of a project I was designing that was supposed to take this really metaphoric lens toward math identity development. And in right triangle trig, we use the metaphor of shadows to look at the shadows of our math story. And then the 3D geometry was cross sections. Like what are these cross sections, these snapshots of your math story that tell a story. And what I wanted to do in that project, aside from exploring all these math ideas and then applying a metaphoric lens to our own math stories, was I wanted my students to get to identify where they experienced a fracture in their math journey and get to go work with a student in that grade as like, public service <laugh>.

Bethany Lockhart Johnson (12:33):