Reading is a complex, multi-faceted process that’s not natural to the human brain. Not only do young readers have to decode the words on the page, but they must also learn the meaning behind words and strings of words creating sentences. In this post, we’ll explore comprehension processes, mental models, and various skills to improve overall comprehension.

Mental models

The Science of Reading is made up of two fundamental parts: decoding and language comprehension.

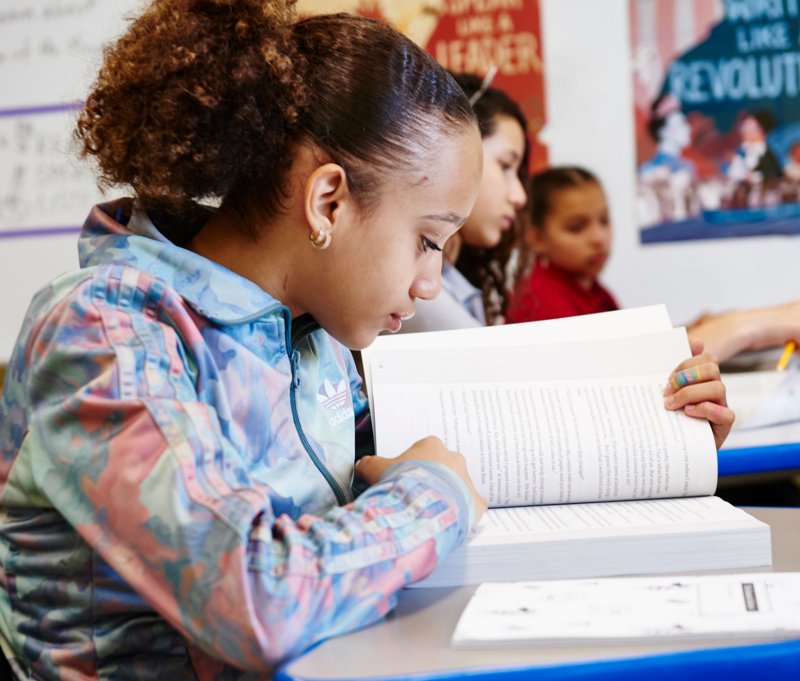

Many students who excel in decoding words struggle with language comprehension due to something called mental modeling, a key component of the language comprehension process.

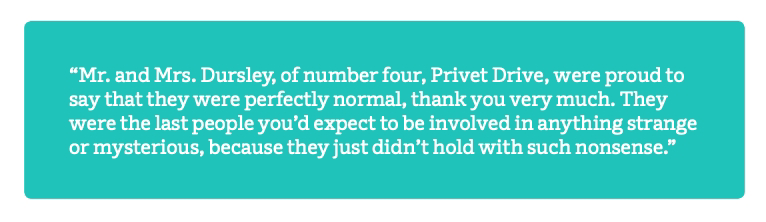

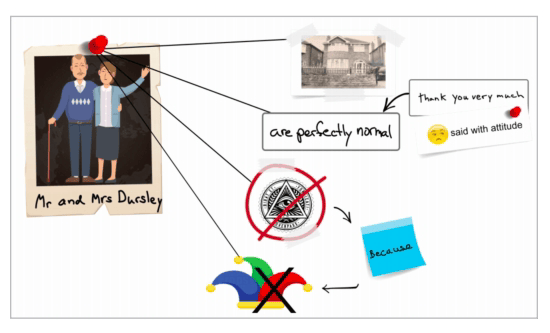

To understand how we use mental models, consider the following excerpt from Harry Potter (Rowling, 1998):

Try to recall as much as you can of the Dursley’s passage.

Most likely, you did not recall the precise wording — at least, not much of it. But you have the ideas: The Dursleys live on Privet Drive, they don’t get involved with weird goings-on, they believe those sorts of things are nonsense.

Researchers use the term “mental model” to describe the structure you created in your memory to perform this feat (see Oakhill, et al., 2015; Willingham, 2017). We can think of a mental model as a network of idea units, perhaps something like this:

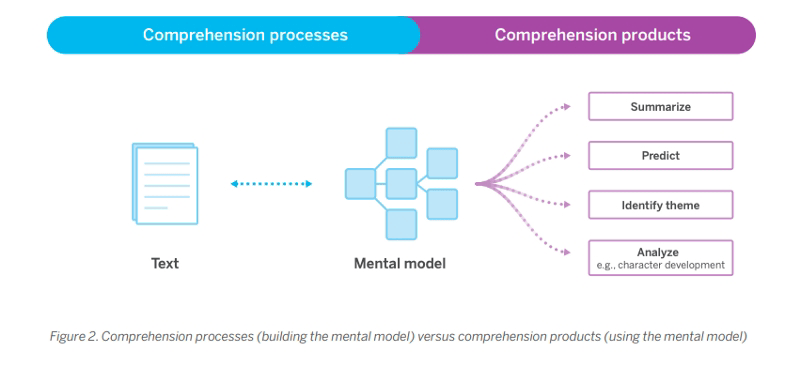

Historically, educators have thought about the process of comprehension — everything that happens after each word is recognized — as a black box. But the Dursley’s passage reveals two levels of comprehension at work: comprehension processes and comprehension products. Comprehension processes are what you do to build a mental model of a text during reading. Comprehension products are the work you are able to do with that model after reading, such as identifying the theme, or a character’s changing beliefs.

If you’ve built a mental model from a text (comprehension processes) but executed it poorly, your answers to questions about that text (comprehension products) will also be poor.

Research on model-building

Research has also documented that two drivers of poor model-building are lack of vocabulary (Carroll, 1993 as cited in Oakhill, et al., 2015; Ouellette, 2006) and dysfluent decoding (i.e., spending too many cognitive resources during decoding, leaving little left over for model construction) (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974; Pikulski & Chard, 2005).

But there are also readers with fluent decoding skills and solid vocabularies, yet poor comprehension (Cartwright, 2010). To better understand why these students are struggling and how to improve their skills, researchers have honed in on specific situations that cause these readers to struggle. For instance:

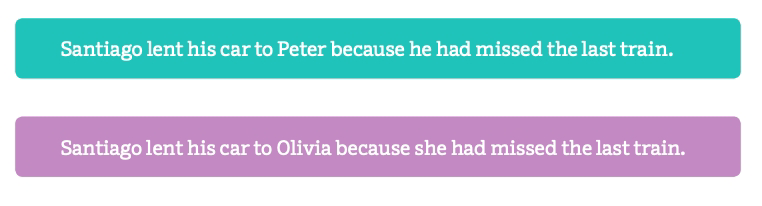

Weak comprehenders struggle with who “he” refers to in the first sentence, but have no trouble with the “she” in the second. Stronger comprehenders get both automatically. Weak comprehenders can figure out the first sentence if given time (and if they notice they didn’t get it on the first read, which many do not), but the additional cognitive effort distracts from model-building (Mesmer, 2017; Oakhill, et al., 2015; Megherbi & Ehrlich, 2005; Yuill & Oakhill, 1988).

The work of leading researchers in the field and others has been combined under the umbrella term “comprehension processes.” There may be as many as 17 comprehension processes that impact students’ ability to build and use their mental models, but we’ve narrowed them down here to list only those most supported by the literature — both through evidence that weak comprehenders struggle with them, and evidence that if these skills are practiced, the targeted skill and overall comprehension improves.

Anaphora

Poor comprehenders are weak in processing pronoun relationships (Megherbi & Ehrlich, 2005), identifying antecedents, and answering questions that require resolution of anaphora (Yuill & Oakhill, 1988). The Santiago sentences above were examples of this.

Gap-filling inference

Writers make assumptions about what can be left unstated. For instance, when reading “Carla forgot her umbrella and got soaking wet,” good readers will seamlessly use their prior knowledge to conclude that it rained. A lack of awareness of when and how to activate background knowledge to fill in the gaps may hinder a student’s ability to make inferences and comprehend the text as a whole (Cain and Oakhill, 1999).

Marker words

Writers use connective words (e.g., so, though, and yet), structure cues (e.g., meanwhile), and predictive cues (e.g., there are three reasons why…) to signal ways that the text fits together. One reason some students struggle with reading comprehension is limited knowledge of the meaning and function of these words (Oakhill, et al., 2015).

Comprehension monitoring

It may seem obvious to good readers that, when something doesn’t make sense, you stop, reread, and try to figure it out. Weaker readers often just keep going or do not recognize that something they are reading is disrupting their mental model.

Text schema

Proficient readers use their knowledge of different types of text to help them build a coherent mental model of what they’re reading. A reader’s expectations about the internal structure of a text are constrained by its schema, or type (Mandler & Johnson, 1977). Each schema has its own set of rules that authors follow to organize the text, from overall topics, to specific vocabulary and syntactic structures (Littlefair, 1991).

Visualizing the model

When students create an imagined visualization of the story they are reading, this enhances their comprehension of the text (Graesser, et al., 1994). As students read and construct a mental model of the text, they constantly refer to and update this model as the story evolves.

All readers, especially students struggling with comprehension, can benefit from instruction in these and other comprehension processes. Looking to incorporate comprehension processes into your everyday instruction? Amplify Reading is a personalized learning program for K–5 students and the only program to explicitly incorporate comprehension processes. Performance within the games is responsive to the student (i.e., it adapts based on how students respond to tasks within and across games). The program is able to target the specific areas of need for each student, allowing them to practice those skills where they struggle and to later use their mental-model-building skills to respond to and analyze increasingly complex texts.

This spring, Amplify is offering a free trial of Amplify Reading through June 30, 2022. Sign up by May 15.