The latest middle-of-school-year data from Amplify show that throughout the spring and fall of 2023, schools across the country made some progress increasing the number of K–2 students on track for learning to read. But that progress is slowing.

Between 2021–2022 and 2022–2023, the number of K–2 students on track for learning to read increased by four to five percent across all grades; however, between 2022–2023 and 2023–2024, the increase was only two percent in each grade. Yet this is not the time for slow progress, because literacy rates in the United States are already a concern. Only half of K–2 students are on track for learning to read, and three in ten students are far behind.

To address slowing gains, schools and districts need to act now to accelerate literacy outcomes.

Early reading: Why we need to act now

The decline is especially urgent for students in kindergarten through the second grade. That’s because of what comes next: third grade, known to be the make-or-break year for reading and future academic success. To put it bluntly, students who are not proficient in reading before entering fourth grade are much more likely than their peers to struggle in school, and they are much more likely to drop out.

“The data is clear—literacy rates at the earliest and most critical time for student development are slowing. Changing this course requires schools and districts to act now and review their approaches in all grades,” says Susan Lambert, chief academic officer of elementary humanities at Amplify. “Schools that deliver strong outcomes focus on building a solid foundation at the start and intervening quickly when students need extra support, rather than trying to play catch up later, when it can be more difficult.”

The good news: We know what to do.

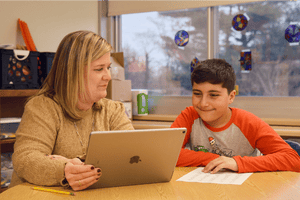

When students receive science-based reading instruction, literacy outcomes improve.

Changing these outcomes requires that districts and schools review the processes and practices they have in place at all levels. Schools that deliver strong outcomes focus on getting students on track—and often ahead—in the earliest grades, because it’s easier to get students ahead from the beginning than to catch them up later.

Districts should:

- Administer universal screening assessments three times per year to monitor levels of risk for reading difficulties.

- Allocate staff to support students who are at risk, spending additional time in literacy instruction beyond grade-level instruction.

- Regularly monitor progress for students who are at risk, making adjustments as needed.

- Ensure that instructional staff gain knowledge about science-based reading instruction and implement high-quality core curriculum with fidelity.

- Instill a love of reading and books during all school-based programs, with the support of caregivers and the community.

“The good news is that when students receive science-based reading instruction, outcomes improve,” Lambert continues. “And, when that instruction takes place in the earliest possible grades, research shows that most students can be taught to read at or approaching grade level.”

More to explore

- Learn more about the Science of Reading.

- Read our article, What is the Science of Reading anyway?

- Read our article, The Reading Rope: Breaking it all down

- Join thousands of educators like you and subscribe to the podcast.