S3-03: Instructional strategies for integrating science and literacy

We’re continuing our investigations around science and literacy with Doug Fisher, Ph.D., professor and chair of educational leadership at San Diego State University. We talk about the importance of integrating science and literacy, as well as practical guidance for teachers who want to unite the two disciplines in their own classrooms.

Listen as we discuss how science and literacy can be powerful allies and specific strategy areas to focus on when integrating the two disciplines. And don’t forget to grab your Science Connections study guide to track your learning and find additional resources!

We hope you enjoy this episode and explore more from Science Connections by visiting our main page!

Douglas Fisher (00:00):

It’s not that you have to become a reading specialist to integrate literacy into science. It’s how our brains work.

Eric Cross (00:10):

Welcome to Science Connections. I’m your host, Eric Cross. This season, we’re making the case for our favorite underdog, which of course is science. Each episode we’re showing how science can be better utilized in the classroom, and making the case for why it’s so important to do so. In our last episode, we examined the evidence showing that science and English instruction can support each other. And now on this episode, we want to give you some more strategies for really making that a reality in your own home or classroom or community. So to help me, I’m joined on this episode by Dr. Douglas Fisher, Professor and Chair of Educational Leadership at San Diego State University. Dr. Fisher is actually someone who has conducted literacy training at my own school, so I’m excited to be able to share some of his wisdom with all of you. Oh, and just a heads up, Dr. Fisher dropped some gems about the ways teachers can integrate literacy and science in their classrooms. So you may want to have a notepad. Ready. And now here’s my conversation with Dr. Douglas Fisher.

Eric Cross (01:12):

Well, Doug, thank you for your time and for being willing to come and talk about literacy and science. I know you’re busy, all over the place, and so I was super-excited that we were able to lock you in and talk about this. And, on this episode, we’re gonna talk about the ways that science and literacy can support each other. And one of the reasons why I’m really excited for you is because you said some really key things for me as a science teacher, when you talked about literacy and supporting students. That just resonated so deeply in me. And I was like, “I need more Doug!” Because we’re on that same frequency. And I know it’s a subject that you’ve spent a lot of time writing about. So can you tell us a little bit about how this became an area of interest or a passion for you? Just literacy, and all of the work that you’ve put into it?

Douglas Fisher (01:54):

Yeah. So I’ve wanted to be a teacher for a really long time. And I went to San Diego State as an undergraduate, and I was taking English class and we were assigned topics. You know, like, you’ll do an assignment, you’ll write a paper for this English class. And I got the topic “illiteracy,” and I was a freshman at San Diego State reading all of these things about adults who don’t read very well or not at all. And I ended up writing my very first college essay on illiteracy — at the time, you know, called illiteracy, at the time. And so I got super interested in this. And so as I moved through college and into my teaching career, literacy became a really important thing for me to think about, because it’s the gatekeeper. You know, you can be taken advantage of, if you’re not very literate. People can use vocabulary against you, if you’re not very literate. We know that people who have higher levels of literacy have better health outcomes. They have better lifespans, longer lifespans. I mean, there’s just — literacy impacts so much more than “Are you reading your fourth-grade textbook?” It really has lifelong implications.

Eric Cross (03:01):

That part that you said about being taken advantage of … I just got a flyer in the mail yesterday. It was one of these mailers that looked like it was an authentic debt-reduction type of thing, but it was really just like a marketing email. If you read the fine print at the very bottom, it had all of this jargon about “This is a paid, you know, for-profit company.” But when you look at it, it had official stamps all over it. And I could imagine if someone’s receiving that, that probably fools a lot of people. Is that kinda like what you’re talking about, like being taken advantage of?

Douglas Fisher (03:28):

Yes. I had a student turn 18, got a letter from a “credit card company” that was offering her daily compounding interest. And if you don’t know what that means — at 23 percent! — if you dunno what that means, you are gonna be a victim. Literacy really influences a lot of our life. It’s also how our brain works. We have a language-based system in our brain. We read, write, speak, listen, and view. And the things we learn, we learn through speaking, reading, writing, listening, and viewing. From what we know, we are the only species that has an external storage mechanism. Like, we have the ability to store complex information outside of our body, in the form of notes. We can type them. We can write them. And we can then go back and retrieve that information, that complex orthographic information later. And it means the same thing. We can say we have a storage system and we’ve been doing this for a really long time. Way back to, you know, hieroglyphics and messages on cave walls. And throughout the ages of humans learning, how to store information that they can re-access again later. That’s become a super-complicated system. It’s how computers operate. And we send messages to each other and we text each other and we write things down, and we’re really good at putting ideas, information out there. Now, if it’s just speaking and listening, then we can forget it. We can say, “No, you said this,” or “I said that.” But when it’s written, and it’s print literacy, you know, it’s the orthographics there, you can go back to the same message and over and over again. Now, you might change the interpretation of it, but the message is still there.

Eric Cross (05:16):

Right. And that is such a key element, at least of modern education, is this written element of it. It’s what many schools live and die by. They’re quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed by it. It’s public. They can see it. And so there’s this heavy emphasis. And why do you think science and literacy can be powerful allies together?

Douglas Fisher (05:38):

Awesome. Well, it’s hard to learn science if you’re not literate.

Eric Cross (05:42):

This is true.

Douglas Fisher (05:42):

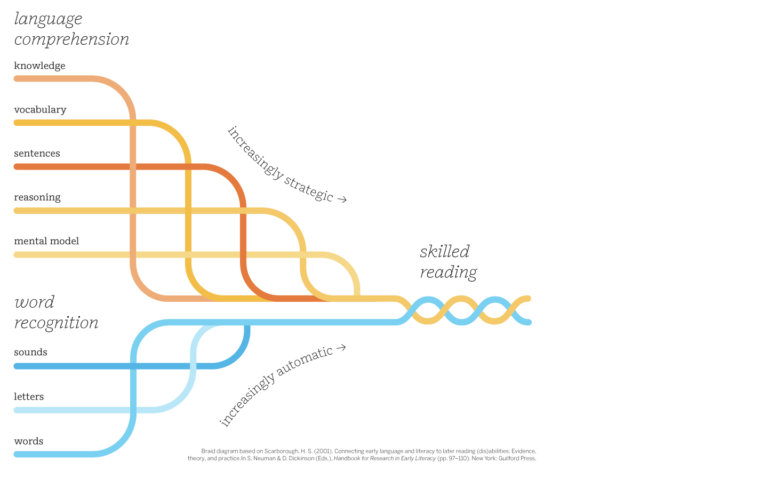

But that’s a one-way direction. And yes, science teachers and scientists do a lot of reading, writing, speaking, and listening and viewing. They use the five literacy processes all the time. When we interview scientists, they spend a lot of their time reading the work of other scientists and writing their findings, writing grant proposals, presenting at conferences, you know. So a huge part of the work of a scientist is not just at a bench conducting experiments. But even if you’re conducting experiments, you’re using your literacy processes to think about what you’re seeing in your experiment. So that’s a one-way direction. And I do think literacy has an influence on science. But since science goes the other way, it influences literacy. As you learn more and you understand more about the world, your background knowledge grows, your vocabulary grows, you become more literate in those different areas. And how you think. So if I’m learning about life science; I’m learning how the world works in a more, biologic physical world. And that knowledge helps me think about when I’m reading a novel, and there’s an appeal to some science knowledge or a concept that gets played with, you know, perhaps time-space continuums … well, if I don’t have the science knowledge of how I think the world works, it’s hard for me to understand what this author is doing. So it does go both ways. They feed each other. And the more literate we become, the more complex science information we can understand. ‘Cause our background knowledge and our vocabulary influence how much we understand about what we read. And as we access more complex science information, it starts to change the way we think about other things in our world.

Eric Cross (07:23):

There was a couple of things that you said in that, but one of the first things that kind of perked my ears is when you said grant proposals. Because I have friends that are scientists — and this is one of the things that when I was in school, they don’t talk about — but how much of their research is reliant upon getting funding —

Douglas Fisher (07:37):

Mm-hmm. <affirmative>,

Eric Cross (07:38):

— which you don’t think about if you’re becoming a chemist or a physicist or a biologist or working in the field, is that that funding, coming from the NSF or anywhere else. And sometimes students ask in class like, “Why am I writing so much? Like, I want to go into science!” Or “I wanna do this!” And this is a real-life example of how the writing could actually apply, in addition to all of the things of collecting data and conclusions and results. But that grant proposal thing just really perked my ears, yeah.

Douglas Fisher (08:01):

And if you can’t write a grant proposal, your ideas and experiments are not gonna get funded. And if you can’t write a strong proposal, that compellingly convinces your readers to fund you, you’re not gonna get funded. But then once you get the grant, you have to write publications. You have to share your work with other people. Make PowerPoint presentations and write journal articles or books or whatever. So it’s a cycle that literacy influences the things we do, including the things we do in science.

Eric Cross (08:31):

Now to get in maybe some data, if you were trying to convince someone that like this happy marriage can exist, what would be like your number one piece of evidence to support this, this back and forth of supporting each other?

Douglas Fisher (08:44):

Awesome. So the quote I’ll often say — and this is from studies from more than two decades ago now — but in general, in high school science, students are introduced to 3000 unfamiliar words, 3000. Each year! Because there are words that are used in a scientific way that are used commonly in other places. And there are discipline-specific words. So 3000 words a year in high school science. The Spanish 1 textbook only has 1500 words in it. So science teachers have double the academic-language vocabulary demand that a typical introductory world-language class has. So just the vocabulary alone should say to us, literacy is gonna be important if you’re gonna learn science. And if you don’t understand these technical words, and you don’t understand the way science uses this particular word in this particular way… . When you say the word “process,” it means something very specific In science. “Division” — cellular division is not the way we think about it in mathematics; there’s a similar concept, but cellular division is different than dividing numbers. And those are words that get used in multiple areas. Then you have all these technical terms that you have to be able to use, to understand the concepts. To share the concepts. To talk to other people. Whether you’re in, you know, fifth grade and talking science, or you’re a university professor, there’s a shared language, appropriate for our grade level, that we have shared meanings of.

Eric Cross (10:22):

And we’re essentially … what I’m hearing you say is … most of the people that are listening to this are science teachers. We’re we’re also language teachers. In a sense.

Douglas Fisher (10:29):

So my frustration is when people say, “Every teacher’s a teacher of reading.” And I don’t like that. I’ve written against that phrase. I don’t think all teachers are teachers of reading, any more than all teachers are teachers of chemistry. Or all teachers are teachers of algebra. But what I will say is the human brain learns through language. And all of us — every teacher that I’ve ever met understands that language is important in my class. If my students don’t have strong listening skills and speaking skills; reading, writing, and viewing skills; I’m gonna have a hard time getting them to learn things. If I can help them grow their speaking, listening, reading, writing, and viewing in my content area, I’m gonna do a service for my learning of my subject and also their more broad literacy development.

Eric Cross (11:16):

- So, at a high level, what does it look like to integrate science and literacy? We’ve done education for the last, what, hundred years?

Douglas Fisher (11:24):

Mm-hmm. <affirmative>

Eric Cross (11:25):

—kind of pretty similarly, right? Kind of siloed way. What does this look like at the 30,000-foot level? You’re a professor, department chair. Run schools. Speak everywhere. Like, when you think about this from that high level, what does it look like?

Douglas Fisher (11:39):

A high level? Every time I meet with students in a science class, you know, biology or fifth grade or whatever? They should be reading, they should be writing, they should be speaking and listening. Every class. So what print do you want them to access? And it can be a primary source document, it can be an article, it can be from a textbook. Are they reading something? Are they writing to you? Because writing is thinking. If they are writing, they are thinking. As soon as their brain goes somewhere else, they stop writing. The pen won’t move or the fingers don’t type. And then speaking and listening, of course, is the dynamic of our classes. So every day we should see some amount of reading, writing, speaking, and listening, viewing in our classes. That’s at a high level. There are some generic things that seem to work across the literacy. So, learning how to take notes. Focusing on vocabulary. Using graphic organizers. These are generic things that as educators we can use in our classes. Then there’s more specialized things. So, scientists and science teachers think differently than historians and literary critics and art critics. So scientists, if you look at the disciplinary literacy work, there’s a whole body of research where they interview and study high-end experts in their field: chemistry, physics, biology, et cetera. And there are some characteristics that were more disciplined, specific. Scientists like cause and effect relationships. They look for them when they’re reading. They like sourcing information. “Where this come from?” “What’s the history of this idea?” Scientists have a long view in terms of time. Historians have a shorter view of time. English teachers have even shorter view of time. Scientists tend to think in long periods of time. And so all of that influences how a scientist reads and how we should apprentice young people after they get past the generic “I know how to take notes. I know how to study my vocabulary. I know how to do summary writing for my teacher in my notebooks and things,” there’s some generic tools. Once we get past those, we need to be looking at specifically how do people in science use literacy.

Eric Cross (13:52):

I’ve never had my thought process of reading deconstructed just now, but we just described how scientists read. I was like, “Yeah, that’s pretty much how I read, right there.” I also like how you said how we should apprentice young people. And I feel like you as the literacy guy, you chose that word very specifically, as far as apprenticing young people. That is a view, I think, that’s really important to hold. ‘Cause that’s what we’re doing essentially … is, if we’re doing what we should be doing, we are apprenticing these young people.

Douglas Fisher (14:18):

Yes.

Eric Cross (14:18):

And helping them develop. Now, let’s imagine there’s a listener out there and they’re interested in getting better at integrating science and literacy instruction. They want to start somewhere. Before we dive in, do you have any initial words of encouragement for the person who’s like, “Everything is like a priority right now,” in their classroom or in their world?

Douglas Fisher (14:37):

Yeah. So I’ll talk about elementary for just a moment. When we’re reading informational texts in our literacy block, we should be reading information that is aligned to what kids need to learn in science and history in, in that grade level. Why are we reading things that are gonna be in conflict with what they’re gonna learn in science later that day in fourth grade, for example? So when we look at our standards, our expectations, what is it that third graders need to know in history, science, mathematics, language arts? And when we’re reading text and we’re learning to apply our reading strategies during our literacy block, why aren’t we reading topics that build our background knowledge for our science time? So we’re seeing some synergy there. We should be looking at life cycles in grades that are appropriate for life cycles and knowing there’s more to life cycles than the frog and the plant or the seed. There are all kinds of life cycles. And we call ’em life cycles for a reason. That’s a general concept. Now in science, we’re looking at this particular lifecycle right now. And so that’s a high level. If we could get more connection to the content standards during our literacy blocks, it would be very good. When we talk about the time at which we call “science” in the day, in more of the K–8 continuum, the science needs to include some primary source documents. Some real things that students are reading. Read about a scientist; read about a scientist’s discovery; read about what they discovered. So that we’re building our background knowledge. So when we go to do things, activities, labs, simulations, we have background knowledge and we understand what we’re experiencing. It can’t be like—I watched this awesome lesson on lenses and the teacher had all these different lenses in the room and the students came in and they were brand new. They don’t know anything. They were picking ’em up. They’re exploring them. They’re trying to figure out, and they’re trying to come up with theories about what this is and how it works. And then the teacher gave them a reading, a short reading, on refraction of light. And they read this thing. And the clarity that they had about what these lenses must do, well! All of a sudden they’re putting them up to the lights! They’re asking if they can go get the lights out of the storage unit! ‘Cause there’s — and they’re shining different lights through the lenses to see what happens to the light. Because that little bit of reading turned some focus on for the students. And it allowed them to take what I’m thinking about, what I’m trying to figure out, how this thing works in another direction. That’s the power of using literacy in our classes.

Eric Cross (17:20):

And what I’m hearing essentially is transfer across disciplines, across content areas, ultimately. And in an elementary school classroom, would it be fair to say, probably the teacher has more autonomy to be able to do that, since they’re teaching all the subjects? But secondary, logistically, planning and those types of things … from what you’ve seen, is it fair to say this kind of needs to be like a top-down, full vertical alignment, to teach like this?

Douglas Fisher (17:45):

I think that would be awesome to do that. But if I’m a sixth grade English Language Arts teacher and I’m working with my sixth grade science teacher, the conversation should be, “What units are you teaching?” Because I’m choosing informational text. My job is to teach them how to find central ideas. My job is to teach them how to find the details in the text. My job is to have them make a claim and support that claim with evidence. The stuff I use is generic. Yes, we do read some literature and some narratives, but we also read about 50% of the text in English around informational text. So if I can help you and accomplish my standards as well, fantastic. So let’s have this conversation and say, “Oh, this is what you’re teaching in science in the next three weeks? I’m gonna choose some texts and we’re gonna analyze ’em for central idea. We’re gonna analyze ’em for details. We’re gonna, for mood or tone or whatever that we’re teaching. And by the way, I’m building background knowledge. So when they come to you, they know some stuff about what you’re going to be teaching next.” So I don’t think it’s impossible to say teams of teachers could come together and say, “What do we believe that our students need to know and learn and be able to do? And then how do we choose things that are gonna help them accomplish exactly that?”

Eric Cross (19:01):

And that’s empowering. Because that’s one thing that we can control maybe is this East-West, peer-to-peer, different content areas. A system may not be able to change as quickly, but I can definitely go talk to my English team or math team and check in and kind of see, “Hey, where do we have overlap in that?” And I know the times that I’ve accidentally had overlap with the teams, it’s super-exciting. And the students have been more bought in! Because it’s like, we’ve done something on the human microbiome and we’ve talked about genetics and all these different things, and then when they read The Giver, or they read some book about genetics, they have all this knowledge. And they’re excited. And they talk about colorblindness or they come to my class and they’re like, “Hey, we read about this!” It’s almost like they saw a magic trick, the fact that these things linked up. And the engagement has been so much higher when it’s the same content in different classes, but through different lenses. At least, that’s what I’ve seen in my years of teaching.

Douglas Fisher (19:54):

I saw a lesson on space junk that was so cool. Middle-school students learning space junk. And the history teacher had a part of it, science teacher had a part of it, English Language Arts teacher had a part of it. And these students, I mean, you watch them look up all the time, ’cause there’s space junk up there. Where’d it come from? Why is it there? What are the politics of this? How do we clean it up? I mean, it was just so interesting to watch them when the teachers came together. And the teachers met their standards in this couple-week-long space-junk exploration. Investigation was met. Politics was met. All these different things. Economy. You know, how much does it cost to clean up this problem? So there’s really cool opportunities when teachers come together and realize we can work together and improve the literacy and learning of our students.

Eric Cross (20:50):

Absolutely. So before this recording, we picked your brain a bit. And I know that there were three specific strategy areas that you wanted to touch on. And one of those — which is kind of coming back to the 3000-words language teachers — was vocabulary. So what are the opportunities that you see, as far as the way of educators to approach vocabulary? Because, you know, there’s a lot. We got a lot of it. The 3000 words.

Douglas Fisher (21:14):

Yeah. There’s a lot of it. So the worry is, we make a vocabulary list and have students look up the words in definitional kinds of things. That’s not really gonna help. Students need to be using the words. They need to be using the words in their conversations, in their writing, in how they think about your content in science. So vocabulary is a huge predictor of whether or not you understand things. Vocabulary is also a pretty good predictor if you can read on grade level. So when we think about vocabulary, there’s something called word solving. You show students a piece of text and you’re reading it, you’re sharing your thinking, and you say, “Oh, here’s a context clue!” Or “I know this prefix or suffix or root!” And in science, a lot of the words are prefixed, suffixed, or root words. We tend to add things together with a lot of prefixes and suffixes and have roots and bases in science. So we can help students think about, “Oh, what does geo- mean? We already know what geo- means here. It means the same thing in this word. Let’s apply that knowledge.” So word solving is part of it, showing students how we think about words that we might not know. The second is more direct instruction of vocabulary. As students encounter the words, we work on what it means, how we say it. We practice it a few times. The process is called orthographic mapping. It’s kind of a scientific idea here. But you have the sound and the recognition of by-the-word, by sight, and what it means. And your brain starts to automatically recognize that word in the future. So I don’t have to slow down, disrupt my fluency, and try to figure out what the word is saying. ‘Cause I’ve seen it enough. I’ve heard it pronounced enough, I’ve pronounced it enough, and I know what it means. So teachers should be saying, “What words in sixth grade science, what words in third grade science, do my students really need to know?” And I’m gonna have them encounter those words over and over. I’m gonna have them use the words. I’m gonna have them see the words. I’m gonna have them say the words. I’m gonna say the word and we’re gonna be over and over with these terms, so that students incorporate them into their normal view of, “These are the things I know about the world.” By the way, when they go to read that next thing, and they understand “geology,” you know, for sixth graders, for example, they know how to say it. They don’t stumble on it. And it activates a whole bunch of memories in their brains. “This is what geology is.” There are branches of geology, there’s physical geology, there’s all this thinking that activates as they read.

Eric Cross (23:35):

There was a practice that I participated in and am trying to incorporate — I don’t know what the name of it is. But essentially what happened was we were dissecting a flower. And the instructor had us name parts of the flower. But we got to come up with our own names for it.

Douglas Fisher (23:49):

Ah.

Eric Cross (23:50):

So, for instance, the stamen we call “the fuzzy Cheeto.” And we all used our own words and then everything was legitimized. And so we went through and learned the whole activity using our own vocab words. But then, in the end, after we presented and talked about it, then the words, the actual academic language was attached to our word. And we were able to say, “OK, the fuzzy Cheeto is the stamen,” and this, this, this, and this. But it was such an interesting practice, because it kind of legitimized all of our definitions. But we weren’t stumbling on these long Latin terms and things like that. Is there a name for that? Or. … ?

Douglas Fisher (24:29):

Yes. I don’t know the name for that. I think it’s really smart. So here’s what I would say about that, is: we don’t learn words, we learn concepts. Words are labels for our concepts. So what that teacher did for you was allow you to develop concept, a concept knowledge. “There’s a part of this plant, it goes like this, we’re gonna call it fuzzy Cheeto. Now I have this concept. And look, it occurred in all these plants. And those people called it that and that other group called it that. We called it a fuzzy Cheeto. Here’s the part of it.” And then the concept is in your brains. And the teacher said, “It’s really called stamen.” And it’s an instant transfer, because you already had the concept. What we often see is students are trying to learn a really hard academic word and the concept for the word at the same time. And so it slows down the whole process. And there’s higher levels of forgetting. Because human beings, we don’t learn words; we learn concepts. If you don’t have the concept, if I gave you a word out of the blue that you’ve never seen, never heard, and a week from now I asked you to remember it, you probably would not, because it didn’t register. It wasn’t part of your schema. You didn’t have a way to organize the information. You don’t have a concept. So that teacher? It’s a great idea. Got you to develop concept knowledge. And then said, “Here’s a real label for it: What some other people called it when they had the chance to come up with their own names.”

Eric Cross (25:50):

Shout out to my teacher, who was—

Douglas Fisher (25:51):

Right.

Eric Cross (25:52):

It was learned then. It was a great practice. And the fact that you’re right, like, I just mean from my own personal experience, I agree that learning concepts versus complicated words. And it’s interesting that you said higher levels of forgetfulness, you know. And you often hear that complaint about it: “Students forget! Students forget!” But this complex topic and this complex word that’s new to me, and I have to remember both of those things.

Douglas Fisher (26:12):

That’s right.

Eric Cross (26:13):

And the other neat thing that it did, is it actually honored the background and like the founts of knowledge of all the different groups in the classroom. You just said something about “this group called it this and this group called it this,” and so by letting different groups share all of those names, now we’re starting to build these kind of interesting connections. That’s at least what I remember experiencing. And so this, even this practice of this approach is very layered, beyond just kind of generating new knowledge of things. So I appreciate that aspect of it. Now another area that you mentioned was complex text.

Douglas Fisher (26:41):

Yeah.

Eric Cross (26:42):

And how we can get students into complex text. So what can we do there?

Douglas Fisher (26:46):

I think science is an ideal place to get students reading things that are hard for them. And I do believe that some parts of school should be a struggle. Not all day, every day. But there should be doses of struggle, which are good for our brains. And these complex pieces of texts that don’t give up their meanings easily allow students to go back and reread the text and maybe mark the text and talk to peers about the text and answer questions with their groups. And the whole point of complex text is to say, “We persevere through it. We may not understand it fully on our first read. But we go back and we might underline, we might highlight. We might write some margin notes. Our teacher might say, ‘What did this author mean here?’ And we go back and look at that part and we take it apart. What do we think about that? And we talk to each other. It’s showing that when we read things, we work to understand. We work through our thinking, often in the presence of other people. And our understanding grows as we go into the text over and over and over again.” So I said geology earlier. There’s about a two-page article on “what is geology” that sixth graders often read. And some kids find it super boring. It’s a once-read, “OK, geology, I don’t really understand it. There’s a bunch of words in here that I don’t understand.” But if you go back to it a few times and you start taking apart, “What are the branches of geology? Oh, I’m gonna go reread that.” How are these two branches related to each other?” “What are the subtypes of each branch of geology?” “How do geologists do their work?” You start asking questions where students are going back into the text. You spend a little bit of time. Now, the introduction to geology, the students know so much more. So whatever you do next— video experiments, whatever—they have a frame of reference, because of that deep, complex read. It’s probably better than simply telling them, “Here’s the information.”

Eric Cross (28:45):

Right. And I even feel like as an educator, when I reflect on my own learning in the classroom, and then looking at it through the perspective of an educator <laugh>, you find this difference between how you were taught and then what the data says good teaching is.

Douglas Fisher (28:59):

Mm-hmm. <affirmative> mm-hmm. <affirmative>.

Eric Cross (29:00):

It’s so easy to slide back into how you were taught!

Douglas Fisher (29:02):

Yeah.

Eric Cross (29:02):

Even though, you know, you mentally assent to, “This is the best way. This is the data shows.” And you find yourself kind of sliding back at times.

Douglas Fisher (29:10):

Yep. And there’s good evidence to support what you just said, that most people teach the way they experienced school. And it is very hard to change that. And people have studied this. And it’s very hard to change that. Because it worked for us. And we have an n of 1, and it worked for us. Now, remember, there were a whole bunch of other kids in the class that it may not have worked for. And we chose to be in school the rest of our lives, and some of your peers did not choose to be in school the rest of their lives. In fact, some of them hated school and found no redeeming qualities of their experience. So just because it worked for us in a case of one, n of 1, doesn’t mean it worked for all of the kids, or even the majority of them.

Eric Cross (29:57):

Very well said. It’s that, what is that, the survivor bias? Survivorship bias? Where you were the one that made it. But you don’t think about all the other folks. ‘Cause we’re thinking about ourselves.

Douglas Fisher (30:05):

That’s right.

Eric Cross (30:06):

Great case for empathy too, is thinking about the people left and right. Because my friends are like, “I hated science.” And I say, “Who hurt you? Like, what did they do? It’s so amazing, so much fun!”

Douglas Fisher (30:16):

“What happened to you? Science is the coolest. Right? It’s so amazing!”

Eric Cross (30:21):

But I also had a unique experience in seventh grade with my teacher who did some of these things, and made it accessible for so many of us, in opening opportunities that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. But you’re absolutely right. That was my story. That wasn’t the story of everybody that was around me. And I think that’s really important. Now, I know this is also a big one for you, but I wanna talk about writing. What are the opportunities that you see in terms of writing specifically?

Douglas Fisher (30:51):

So would love it if science teachers had short and longer writing tasks in the science time. Of course, you can integrate some of the science writing, the longer ones, in the English language arts time, especially if you’re the elementary teacher and you can have control of the whole day. But I said this earlier; I’ll say it again. Writing is thinking. While you are writing, there’s nothing else you can do but think about what you are writing. Your brain cannot do something else. So if a science teacher wants to know, do their students really understand the concepts? Have them write. Now some of the shorter ones, I like something called “given word” or “generative sentences”: “I’m gonna give you a word: CELL. C-e-l-l. We’re in science. I want you to write the word ‘cell,’ c-e-l-l, in the third position of a sentence. So it’s gonna go word, word, cell, and then more words.” You could also say, “I want the sentence longer than seven words,” or whatever. But the key is, I’m telling you where I want the word. You will know instantly if your students have a sense of what the word “cell” means in the context of science. If they write “my cell phone,” they don’t get it. If they write about spreadsheet cells or jail cells or whatever, they didn’t get it. But if they talk to you about plant cells and animal cells and the components of those cells, and then once they have that sentence down, you can say to them, “Now write three or four more sentences that connect to that sentence.” It’s super simple. So whatever concepts you’re teaching, put ’em in a specific position. Now you don’t have to only put it in the third position. You can say the first position, the fifth position, the fourth position. But it forces them to think about what they know about the word and then how to construct a sentence for you. That’s a very simple way to get some writing from your students that helps you think about what they understand. Other kinds of writing, you can have quick writes, you can have exit-slip writes. There’s something in the research space called the muddiest part, where halfway through the lesson you have them write so far what has been the least understood or the most confusing part of this lesson. And they do a quick write, right there, at the muddiest part. And as a teacher, you flip through these and you start to say, “Oh, these are the points that are confusing to my students.” So if 80% of them all have the same thing, I gotta reteach that. If these five got, “This is the muddiest part,” If these five thought, “This is the muddiest part,” these seven, “I thought this was the muddiest part,” what do I need to do? Because it’s gonna be hard to move forward if this is their area of confusion. There are also all kinds of writing prompts that have a little bit longer. My favorite one is RAFT. What’s your Role? Who’s your Audience? What’s the Format? And what’s the Topic we’re writing about? Super flexible writing prompt. When you teach something, we don’t want students to only think they write to their teacher. So your role is an atom. You are writing to the other atoms. What do you wanna write about? What’s the topic? What’s the format of it? Is it a love letter? Is it a text message? Is it … so we, we mix it up with students in saying, how do they show some knowledge through a prompt that we give them? And then of course, longer pieces as they get older. More opinion pieces through fifth grade. More claims and arguments starting in sixth grade. So that they’re starting to see, “I have to use the evidence from things I’ve learned, read, listened to, watched, and construct something: an opinion, an argument where I back it up with reasons or evidence.” And those longer pieces, you know, less frequently. The shorter pieces, pretty regularly. So the teacher sees the thinking of the students.

Eric Cross (34:29):

When you were speaking about these really creative writing prompts, there were specific students coming into mind, that were coming into mind … they’re, they’re great science students, but they also have this really strong artsy side drawing, creative writing, and things like that. And when you said something about atoms talking to each other, it elicited, in my brain, certain students that would really love this aspect of creativity in the sciences. And it’s not how we’re typically trained as science teachers, to kind of incorporate this, like you said. A book of props. But I’m imagining, like, as a science teacher, if I took this, this would be a great way to reach more students to be able to show what they know, in a way that might resonate with their own intrinsic “Oh, I get to write creatively!” So I was kind of writing furiously as you were sharing all that information there.

Douglas Fisher (35:12):

So here, I’ll give you another example for elementary people. Again, with RAFT. There’s a book called Water Dance. It’s a pretty popular book for elementary teachers. It’s really about the life cycle of water. For example, you are a single drop of water. You are writing to the land. The format is a letter. And you’re explaining your journey. Now, if they can do this, they’re essentially explaining to you the cycle of water. But you got it in a way that people are now, “Oh, I’m a drop of water. So it’s me. My perspective. Where do I go from? Where do I start?” Because you can start anywhere in the cycle, right? My drop could have started in the clouds. My drop could have started in the ground. My drop could have started in the lake. But it has to show you the journey. So there are many ways of showing you the right answers.

Eric Cross (36:02):

And that’s using the RAFT protocol.

Douglas Fisher (36:04):

That’s RAFT: Role, Audience, Format, Topic. It’s been around 20 or 30 years.

Eric Cross (36:09):

You just gave the name to something a teacher shared in our podcast community, Science Connections: The Community, on Facebook. Teacher shared a Google slide deck and on it were just three slides. And the role that the student had to have is they had to show, then tell, the story of a journey of a piece of salmon being eaten, a piece of starch from pasta being eaten, and then an air molecule in a child’s bedroom. And they had to give the path of travel and the experience from the mouth and then breaking down into protein and all those kinds of things. And this teacher shared it and I wish I knew the teacher’s name because I wanna give ’em credit, but they shared it. And so I used it with my students and then had ’em read aloud their stories and dramatize it. And they were so into it!

Douglas Fisher (36:49):

So cool.

Eric Cross (36:50):

But through it, I was able to see that they understood different parts of the body. They understood cell respiration. The whole thing. And it was fun! To watch them get so into this creative writing. And now I know the name of it. That’s been 30 years they were using RAFT. So you just talked a bit about complex texts and writing. And before we go, I wanted to circle back to something that you said, because I think it’s important, and if you could elaborate on it a little bit, about the value of struggle. Can you talk more about that?

Douglas Fisher (37:21):

Sure. I do believe in a lot of the U.S. we’re in an anti-struggle era of education. And it predates Covid. I think it made it worse during Covid. We front load too much. We pre-teach too much. We reduce struggle. We quote, “over-differentiate” for students. And there’s value in struggle. The phrase, “productive struggle” — if you haven’t heard it, Google productive struggle — it’s an interesting concept, that we actually learn more when we engage in this productive struggle. Now, productive struggle originally came from the math world, and it was this idea that it’s worth struggling through things to learn from it, that you’re likely to get it wrong, and then there was productive success. And there are times when we want students to experience success and we make sure we put things in place for productive success. But there are times where we want them to struggle through a concept. ‘Cause it feels pretty amazing when you get on the other side, when you know you struggled and you get to the other side. If you think about the things, listeners, think about the things in your life where you struggled through it and you are most proud of what you accomplished. I want students to have that. I don’t wanna eliminate scaffolding, eliminate differentiation. But I do want some regular doses of struggle. So if you look at the scaffolding, we have a couple choices. We have front-end scaffolds, distributed scaffolds, and back-end scaffolds. Right now we mostly use front-end scaffolds: We pre-teach, we tell students words in advance, that kind of stuff. But what if we refrained from only using front-end scaffolds, and we use more distributed scaffolds, when they encounter. So there’s a difference between “just in case” and “just in time” support for students. So we tend to plan on the “in advance, here are all the things we’re gonna do to remove the struggle before students encounter the struggle.” What if instead we said, “Let them encounter some struggle. Here’s the supports we’re gonna provide. We’re gonna watch; we’re gonna remove those scaffolds, and allow them to have an experience of success, where they realize, ‘I did it. I got it.’” Every science teacher I’ve ever worked with, when they do an experiment or a lab or simulation, they are looking for productive struggle. They don’t tell the answers in advance. They don’t tell if the answers are right. That’s your data. What does your data tell you? I mean, this is what you do. But then the other part of your day when you move into, like, reading, you don’t do that. You fall into the trap of removing struggle. And so allow them to grapple with ideas. Allow them to wonder what words mean. Allow them to say, “I’m not getting this, teacher! It’s really frustrating!” And you say, “Yeah, this is really hard. This is why we’re doing it at school. ‘Cause it’s really hard. If it was easy, I’d have you do it at home. But we’re doing it here, ’cause it’s really hard and it’s OK not to get it at first.” And create a place where errors are seen as opportunities to learn, and struggling through ideas and clarifying your own thinking and arguing with other people to reach an agreement or reach a place where we agree to disagree is part of the power of learning.

Eric Cross (40:38):

There’s a teacher, who I took this from. My master teacher when I was student teaching. And she said that there’s no such thing as failure in science, just data. And I took that same mantra. And I resonate with what you said about how science teachers, all of us, hold onto that productive struggle, because it’s part of being a scientist. It’s part of the experiments. That genuine “aha” moment. Or it didn’t work out? That’s great! That’s totally fine! Let’s write about it and let’s take photos and let’s publish it and let’s be scientists. That’s totally true. As we wrap up, Dr. Fisher, is there any final message that you have to listeners about bringing science and literacy together? I know you speak everywhere, but for everyone that’s listening, if you can put out your encouragement or message or suggestion … you’ve given so many great tips and practical applications. But, any final thoughts on the subject?

Douglas Fisher (41:32):

I think many science teachers are intimidated because they think they have to be reading teachers. And there’s a knowledge base to reading. And some teachers are reading teachers and science teachers, and I don’t wanna dismiss that. But it’s not that you have to become a reading specialist to integrate literacy into science. It’s how our brains work. And so as you think about the way in which you are learning and the ways in which you want your students to learn, what role does language play? What role does speaking, listening, reading, writing, viewing, play in your class? And then provide opportunities for students to do those five things each time you meet with them.

Eric Cross (42:12):

Dr. Fisher, thank you so much for being here and for your encouragement, and sharing your wisdom and experience. And then personally serving my city, here in San Diego, and my students, when they make it to your high school and ultimately the alma mater of San Diego State University.

Douglas Fisher (42:30):

That’s right.

Eric Cross (42:31):

Yeah. We really, really appreciate you in serving all kids and lifting the bar and making things more equitable for all students. And encouraging teachers. So thank you.

Douglas Fisher (42:39):

Thank you very much.

Eric Cross (42:42):

Thanks so much for listening to my conversation with Dr. Douglas Fisher, Professor and Chair of Educational Leadership at San Diego State University. Check out the show notes for links to some of Doug’s work, including the book he co-authored titled Reading and Writing in Science: Tools to Develop Disciplinary Literacy. Please remember to subscribe to Science Connections so that you can catch every episode in this exciting third season. And while you’re there, we’d really appreciate it if you can leave us a review. It’ll help more listeners to find the show. Also, if you haven’t already, please be sure to join our Facebook group, Science Connections: The Community. Next time on the show, we’re going to continue exploring the happy marriage between science and literacy instruction.

Speaker (43:26):

I had this moment of realization I felt a few months ago: I’m like, if I don’t teach them how to use the AI as a tool, as a collaborator, then they’re gonna graduate into a world where they lose out to people who do know how to do that.

Eric Cross (43:39):

That’s next time on Science Connections. Thanks so much for listening.

Stay connected!

Join our community and get new episodes every other Wednesday!

We’ll also share new and exciting free resources for your classroom every month!

Meet the guest

Douglas Fisher, Ph.D., is professor and chair of Educational Leadership at San Diego State University and a leader at Health Sciences High & Middle College having been an early intervention teacher and elementary school educator. He is the recipient of an International Reading Association William S. Grey citation of merit, an Exemplary Leader award from the Conference on English Leadership of NCTE, as well as a Christa McAuliffe award for excellence in teacher education. He has published numerous articles on reading and literacy, differentiated instruction, and curriculum design as well as books, such as The Restorative Practices Playbook, PLC+: Better Decisions and Greater Impact by Design, Building Equity, and Better Learning Through Structured Teaching.

About Science Connections

Welcome to Science Connections! Science is changing before our eyes, now more than ever. So…how do we help kids figure that out? We will bring on educators, scientists, and more to discuss the importance of high-quality science instruction. In this episode, hear from our host Eric Cross about his work engaging students as a K-8 science teacher.