Part of the magic of reading is that it opens up endless knowledge.

This seems to suggest a logic of first learning to read, then reading to learn.

But experts in education and the Science of Reading have actually turned that logic on its head. They say that knowledge matters first.

That’s why our elementary literacy curriculum Amplify Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA) delivers literacy skills grounded in knowledge. In fact, it’s one of only a few such programs recently recognized by the Knowledge Matters Campaign for excelling at building knowledge.

Background knowledge is essential to literacy

Reading depends on both decoding and comprehension. Many years of classroom observation and received wisdom have supported the supposition that comprehension must be taught as a discrete set of skills, while decoding arises more naturally.

But an established body of cognitive science research now shows that early literacy skills are best built deliberately, on a foundation of knowledge. In fact, knowledge-building is not a result of reading and comprehension; it’s a vital prerequisite and a fundamental part of the process. In other words: The more you know, the faster you learn.

But typically, literacy instruction focuses on decontextualized skills—finding the main idea, making inferences—rather than the content of texts and resources that students engage with.

Teachers often put the skills and strategies in the foreground, like a skill of the week, then they bring in texts that they find well suited for demonstrating the skill or strategy. So instead of harnessing skills and strategies to content, they’ve got the cart before the horse,

Natalie Wexler, author of The Knowledge Gap told host Susan Lambert on Amplify’s Science of Reading: The Podcast. “What we’re doing in elementary school can plant the seeds of failure in high school.”

When students lack access to the same sources of knowledge, they also lack equal access to reading success. That’s what experts call the knowledge gap, and it needs to be narrowed, or even eliminated, in order to achieve equality.

Wexler adds that a skills-first approach may also—despite educators’ best intentions—challenge kids’ self-esteem. “We are telling kids, ‘Just do this and you’ll become a better reader and better student.’ They do it diligently, but then if it doesn’t seem to work, they may blame themselves.”

A closer look at the knowledge gap theory

Let’s say you’re handed a passage of text describing part of a baseball game. You read the text, and then you’re asked to reenact that part of the game. Which is most likely to help you do so?

- Your ability to read

- Your knowledge of baseball

- It makes no difference

If you answered “2,” you’re batting 1,000. This example summarizes an influential 1988 study that concluded that the strongest predictor of comprehension was knowledge of baseball. Even the weak readers did as well as strong readers—as long as they had knowledge of baseball.

Not all students arrive at school with the same prior knowledge.

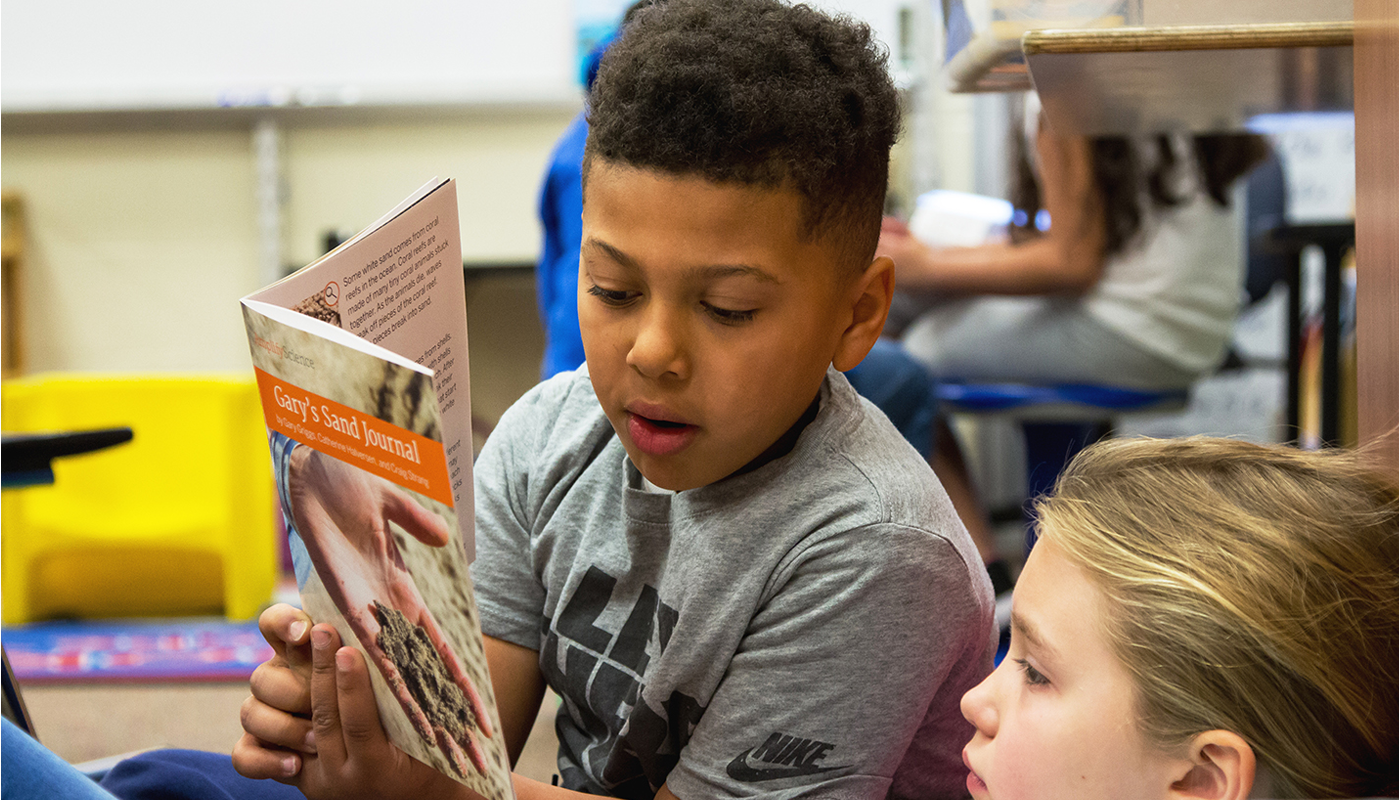

If a student who’s never heard the word “yacht” is asked to read and analyze a text passage about the Henley Royal Regatta, it’s a good bet that they won’t do as well as a student who has. Not all students visit museums, have a library of books at home, or travel outside the country or even city where they live.

Wexler cites cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham in her powerful Atlantic article “Why American Students Haven’t Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years.” He says,

“The failure to build children’s knowledge in elementary school helps explain the gap between the reading scores of students from wealthier families and those of their lower-income peers…a gap that has been expanding—[w]ealthy children are far more likely to acquire knowledge outside of school. Poorer kids with less-educated parents tend to rely on school to acquire the kind of knowledge that is needed to succeed academically—and because their schools often focus exclusively on reading and math, in an effort to raise low test scores, they’re less likely to acquire it there.”

How we can support teachers

Change can be challenging, says Wexler: “When you’ve been doing something for years in the belief that you’re helping kids, it can be difficult when somebody comes along and says, actually, you may be holding them back.”

We can support educators by increasing awareness of the Science of Reading, the role of knowledge in literacy, and access to tools that support educators in delivering knowledge with literacy. We can also show them what learning looks like in classrooms where all students acquire knowledge and literacy regardless of background.

We can, for example:

- Challenge the assumption (which predates Google) that when kids encounter an unfamiliar word or topic, they can just look it up. Doing so can impose a cognitive load that can actually interfere with learning.

- Seek out high-quality products and programs that intertwine literacy and knowledge.

- Remind educators and decision-makers that—as Wexler puts it—”the students who blossom the most with a knowledge-building curriculum are the students who, in a skills-focused system, would be the kids in the lowest reading group. They are able to offer valuable insights and feel like full members of a classroom community.”

About Science of Reading: The Podcast

Science of Reading: The Podcast delivers insights from researchers and practitioners in early reading. Each episode takes a conversational approach and explores a timely topic related to the Science of Reading.