There’s a difference between the ability to sound out words on a page and the ability to truly understand their meaning. That difference? Reading fluency.

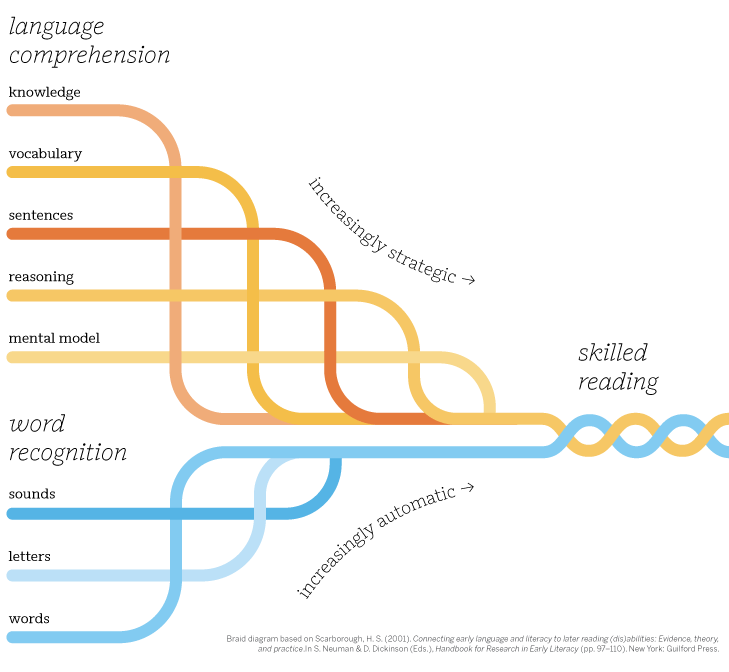

Fluency is one of the five foundational reading skills. (The other four, as you likely know, are phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.) Fluency connects readers not just to words, but to emotions and expressions, characters and connotations. And it’s also where reading really starts to foster joy.

In this post, we’ll explore what fluency is, why it matters, and how to successfully incorporate it into your literacy instruction.

Defining fluency

The International Literacy Association defines reading fluency as “reasonably accurate reading, at an appropriate rate, with suitable expression, that leads to accurate and deep comprehension and motivation to read.”

In other words, fluency is not just reading fast. And it goes beyond merely decoding words, to developing a deep understanding of what they’re trying to say. Fluency allows readers to connect ideas, recognize patterns, and infer meanings.

“I call fluency the bridge to comprehension,” says Kent State literary education professor Tim Rasinski, discussing the topic on Amplify’s Science of Reading: The Podcast.

Why fluency in reading matters

Rasinski is also director of Kent State’s award-winning reading clinic, and in his podcast episode, he describes encountering students as old as grade 5 who have decoding skills, but not fluency. “[These students] can sound words out, but if you were to hear them read orally, it would be slow, laborious reading in a monotone,” he says. According to Rasinski, these students aren’t getting “much joy and satisfaction, or even comprehension” from their reading.

While oral expression in reading is not the ultimate goal, it is an indicator. “The way you read orally reflects the way you read silently,” Rasinski says. “Most of us would say when we read silently we ‘hear’ ourselves with our internal voice.”

When readers develop fluency, they also develop:

- Comprehension. As decoding becomes more effortless, readers can focus on understanding meaning. Fluent readers recognize words automatically, allowing them to dedicate cognitive resources to complex sentence structures and connections among ideas. They grasp both main points and nuances. All told, they get what they’re reading.

- Confidence. Fluent readers are more likely to feel accomplished, proud, and motivated with regards to their reading abilities. And it’s a virtuous cycle: As their confidence grows, they’re more likely to engage in and enjoy reading—and continue to improve.

- Vocabulary. Fluency plays a significant role in vocabulary acquisition and language development. Fluent readers encounter a larger variety of words in context. This exposure enhances their language and communication skills across academic topics and life experiences.

- Academic success. Fluency helps students read to learn. As students advance through school, fluency becomes increasingly important for comprehension and analysis of more advanced and content-rich texts.

- Emotional connection. Fluency enables readers to connect with the characters, emotions, experiences, and implications in a given text. That’s what makes reading immersive and enjoyable—in the moment and for a lifetime.

The fluency journey: learning and assessment

The Science of Reading tells us that foundational reading skills must be taught explicitly and systematically, and fluency is no exception. Developing reading fluency is a gradual process that requires consistent practice and exposure to different types of texts. There are several stages and skills that support the development of reading fluency.

- Fluency starts with accuracy in decoding. As students practice and improve their phonics skills, they can accurately recognize and decode more and more words. This helps them move from laborious reading toward more efficient reading.

- Speed comes as a result of accuracy. As students become more accurate in decoding, they can read words more quickly. Accuracy helps reduce the time it takes to identify and process each word, allowing for a smoother and faster reading experience.

- Fluency practice helps with automaticity. And the more students develop both accuracy and speed, the more they develop automaticity.

As you may know, there’s a tool called Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) that reading professionals use as a quick-read thermometer of sorts to measure reading speed and accuracy. It’s a simple assessment, measuring how many words a student reads correctly in an unpracticed passage. It’s considered one of the best indicators of a student’s reading progress.

“It works! It has validity. It gives us good, useful information,” says researcher, educational consultant, and author Dr. Jan Hasbrouck on Science of Reading: The Podcast. That’s why it’s widely used—but, she adds, it’s also widely misunderstood.

It is a reliable and helpful measure of fluency in terms of reading rate and accuracy, she says. At the same time, “It was unfortunate to put the label ‘fluency’ on it,” she says. “We reading teachers think of fluency as something much more multifaceted and complex that at minimum includes prosody, or expression. It is accuracy, rate, expression, metacognition, background knowledge—it’s all of this stuff that really experienced reading teachers think of as fluency.”

Fluency best practices for literary instruction

Automaticity frees up cognitive space for comprehension, but fluency isn’t just about reading fast—it’s also about making meaning, which is where prosody comes in.

Prosody refers to the rhythm, intonation, and expression used by someone reading aloud.

But it’s not just for the natural performers in the classroom. Prosody can be influenced. How do we help students develop that external, and internal, prosodic voice?

Through targeted read-aloud practice. By explicitly teaching students about prosody and providing systematic practice opportunities, educators can nurture fluency and comprehension simultaneously—a connection to overall reading success that is well-supported by evidence-based research.

Some fluency strategies include:

- Reader’s Theater in the classroom: Students don’t have to be skilled actors to take on roles and read from scripts. Theater activities allow them to practice recognition and expressions of drama and emotion as they bring the lines to life.

- Assisted reading: When students read aloud simultaneously with a more fluent reader, they practice their own skills while also hearing someone else make meaning of the same text. This can also take the form of choral reading, i.e., students reading aloud as a group, focusing on using appropriate intonation and expression. Reading together allows them to practice prosody in a supportive and collaborative environment.

- Consistent reinforcement and rewards: Rasinski works with students on snippets of text, first with prosody modeled by teachers, then practiced alone and together (repeated reading), then performed for each other or even parents or other adults who offer praise. This regular practice helps boost the confidence and motivation that assists students in developing fluency. “We want children to experience reading success every single day,” says Rasinski.