When you learn to read, you don’t learn just to pronounce words—you learn to understand them, and how they work together to convey meaning. In fact, it almost goes without saying that vocabulary is an essential, non-negotiable building block of literacy.

But there’s actually a lot to say about vocabulary. And in the context of literacy instruction, it’s about much more than memorizing and amassing words and definitions.

If there’s one word we need to better understand to explore the importance of vocabulary, it’s…vocabulary. So let’s explore the word’s full definition, as well as how it fits into best practices in literacy instruction.

Why is teaching vocabulary important?

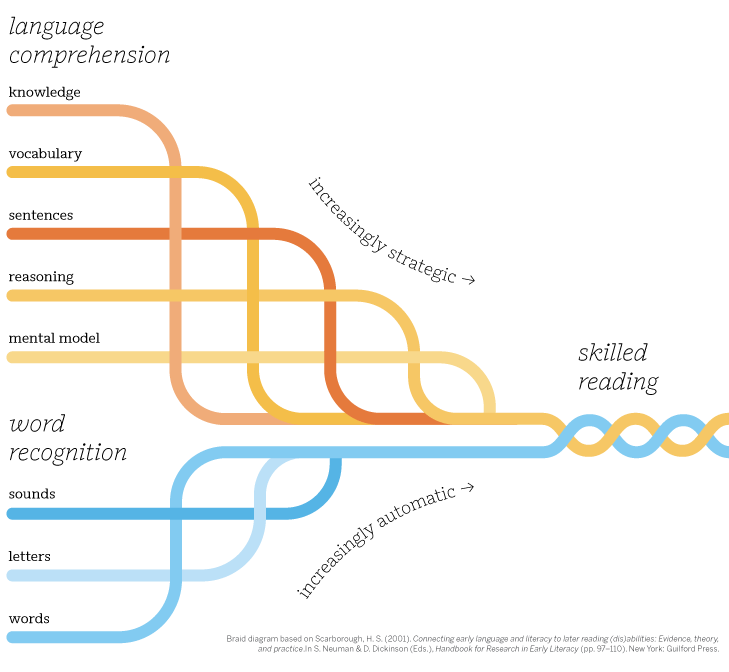

Vocabulary is one of the five foundational skills in reading and a key strand in the Reading Rope. As a word, it refers to the collection of words that we understand and use in language.

Vocabulary includes both the words we recognize and comprehend when reading or listening (receptive vocabulary) and the words we can use accurately and effectively when speaking or writing (expressive vocabulary).

But our vocabulary isn’t just a list of words and their definitions. “Words are interrelated,” says Nancy Hennessey, former president of the International Dyslexia Association, on Science of Reading: The Podcast. “We’re storing words in networks of meaning.”

Entwined in those networks is background knowledge. We can memorize words in a vacuum, but they’re not really part of our vocabulary until and unless they’re grounded in what we know.

“Background knowledge and vocabulary are the main support beams in the comprehension house,” says Hennessey.

How to teach vocabulary as students grow

First, it’s important to note that tactics and emphasis can and should shift as readers develop skills. As Hennessey notes, we can measure vocabulary in terms of both breadth and depth. These elements play distinct yet complementary roles in literacy development.

Vocabulary breadth refers to the sheer number of words a reader knows and recognizes. A broad vocabulary enables readers to understand a wide range of texts and communicate effectively in various contexts.

In the early stages of reading development, educators might emphasize increasing vocabulary breadth—exposing readers to diverse texts, books, conversations, and experiences. In this way, new readers start building a foundation of familiar words that they can understand and use.

As students learn more, instruction can shift from breadth to depth. Here’s where educators dig into the intricacies of word meanings—exploring synonyms, antonyms, contexts, and connotations. A deep vocabulary allows readers to grasp subtle nuances in language and engage in more sophisticated forms of expression and comprehension.

Vocabulary activities and instruction

Hennessey has developed a four-pronged approach to vocabulary instruction, grounded in the Science of Reading. The four prongs are:

- Intentional instruction: explicitly teaching the meaning of specific words.

- “Incidental-on-purpose” instruction: helping students understand new words as they come up.

- Intentional teaching of independent word learning strategies: giving students tools to help them determine the meaning of words on their own (e.g., using morphology, context clues, or even glossaries).

- Development of “word consciousness”: getting students interested in how words work to convey meaning, uses of figurative language, etc.

“These approaches are based on the fact that we know we need to explicitly teach words,” Hennessey says, “but we also need to continue developing vocabulary through oral experience and reading, because we can’t teach all the words that our students need to know.”

In the context of literacy development, vocabulary instruction is not rote memorization of lists of words. And, according to Hennessey, that’s not the way kids relate to it either. Students bring natural interest and curiosity to exploring figurative language, playing with palindromes, and finding and learning what she calls “$20 words.”

When we integrate these activities into incidental or incidental-on-purpose instruction, Hennessey says, “we can embed this excitement and understanding of how words play such an important role in our lives.”